|

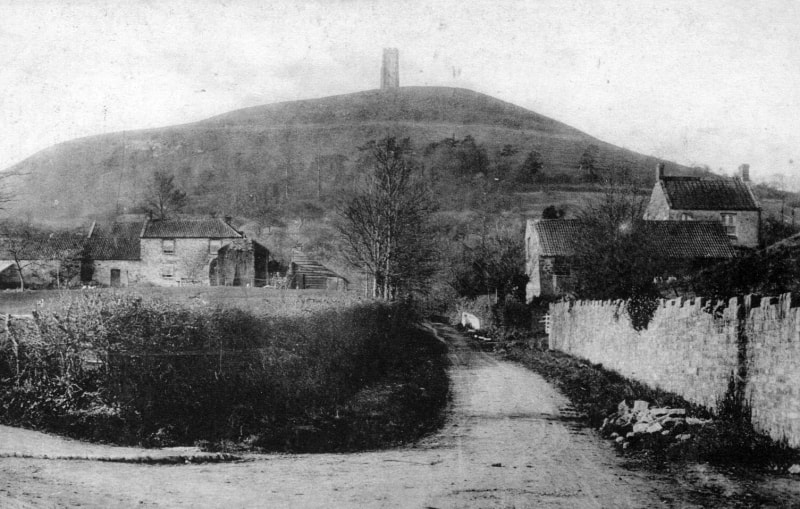

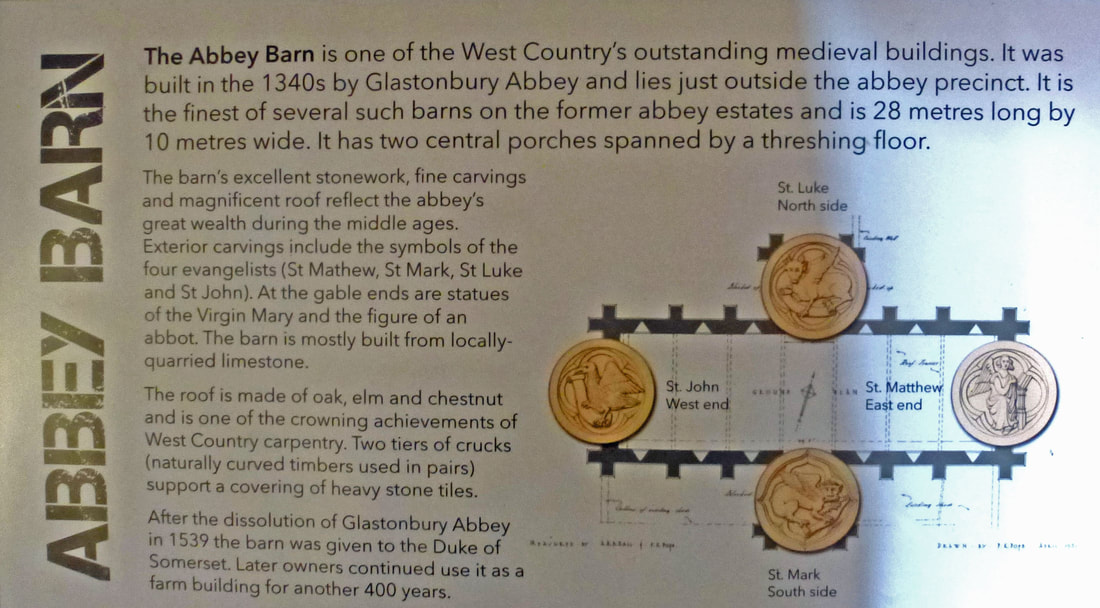

From the early days of ‘the Group’, its leaders and members regarded Glastonbury as a special destination. Individuals from subsequent London Cabbala groups in the 1960s and early ‘70s also headed westwards, to visit the town and surrounding area when the opportunity arose. Members from Tony Potter’s group, for instance, were encouraged to go, as somewhere to ‘recharge their batteries’. It was also a place to tune in to the unseen, to visit both Tor and Abbey, and ponder the intertwining of ‘native’ Christianity and more esoteric traditions. The visits of Alan Bain ‘Desolation and desecration. Sorrowful stones that lament past glories. They have no pride, no grandeur but a fierce sense of urgency that something must be done. They would be satisfied with nothing less than complete restoration in their original form, and this is impossible. Yet there is no despair, for they seem, also, to await the next chapter in the drama that is Glastonbury, almost as if they know what it is to be…’ So wrote Alan Bain, the main leader of the Soho Group, when he visited the town in 1960. ‘Its destiny’, he said, ‘is not yet fulfilled, if it ever will be...Holy it was, and Holy it is...That it exists at all makes me infinitely glad, but the state of its desolation leaves me correspondingly sad.’ It wasn’t his first visit to the town, and although we don’t have a full account of his journeys there, the notes that survive reveal that a couple of years earlier in 1958, he recorded a kind of pathworking, an imaginative visualisation of a pilgrimage to Glastonbury. In this, he ‘sees’ seven men walking to Glastonbury clad in white cloaks, then welcomed into the Abbey, where he notes in detail its layout and architecture at this apparently medieval period. This is how he describes breakfast on the morning after their arrival, when they have been lodged in the pilgrims’ quarters: ‘They then go along to building ‘W’ [diagram of Abbey supplied] which they enter, and sit down at a long bare wooden table and eat blackish bread which is very delicious, newly baked, with thick white (onion?) soup. A guide then enters, name of Jason or James, wearing a brown cloak with hood thrown back, not over head, a cord tied around his middle with tasselled ends. He has a plump figure and face and shiny bald head…He leads them to the Abbey.’ The pilgrims may be, he intimates, ‘the Company of Avalon’, a ‘Society’ which ‘had to do with magic’. In his later notes from 1960, he records an impression that his own ‘apprenticeship’ began in Glastonbury in 1523. Or was it, he asks, 1253? Either way, he plainly formed a strong personal bond with the Abbey and Glastonbury as an important centre of British Christian history, maybe even a form of esoteric Christianity. Alan took a series of photographs during his visit in 1960, and more later in the 1980s, some of which can be seen in this post. They carry the slightly melancholic atmosphere of Glastonbury in the middle of the 20th century, when it was less well-tended and less frequented than it is now. Alan's photos below show the passage from the Abbey to the High Street, the frontage of the ancient George & Pilgrim's Hotel, and the street itself. (The photos have been retrieved from his former website.) The British Jerusalem Glastonbury had long been a place of pilgrimage; it is sometimes called the British ‘Jerusalem’, as it is said to be where Joseph of Arimathea (the uncle of Christ) arrived in these Isles, bearing the sacred cup from the Last Supper. (At one time it was perfectly possible to arrive at Glastonbury by boat.) Joseph, so legend has it, planted his staff on Wearyall Hill where it sprang to life as a hawthorn bush. The Holy Thorn bush is still venerated through its descendants planted around the town to this day. It flowers both in winter and in May, and the Queen receives a spray of its flowers on her Christmas breakfast tray, a royal tradition stretching back to the reign of James I. Glastonbury has a layering of spirituality and myth which is unique in the British landscape. Its geography reinforces this mythical quality, with the high Tor towering dramatically over what was once an island in the Somerset Levels. It is startling even today when glimpsed on the approach to Glastonbury, and must have been revered by those arriving by boat, or over the causeways and ridgeways long ago. These flat lands were once waterlogged for much of the year, and in the Iron Age were inhabited by people who lived in lake villages. (See here and here.) The area is also connected with legends of King Arthur. His sword Excalibur is said to have been forged in Glastonbury, and a story tells how the Nine Sisters of Avalon bore the dying king across the lake to his final resting place in the immortal isles beyond. (See Chapter One, 'The Company of Nine', in my book The Circle of Nine ) Two springs – the White and the Red – rising at the base of the Tor, are also considered sacred and to have healing properties.  Alan Bain took these three images of the Red Spring and Chalice Well in 1960 - two of the well itself and one where the spring gushes out onto the lane, and people bring their bottles to fill up with the iron-rich water, said to promote healing and health In medieval times, Glastonbury was primarily a place of Christian pilgrimage, but after the Reformation, the Abbey fell into ruin. Then in the early 20th century, the town and the Tor began to draw in those interested in magical, psychic and visionary work – the Order of the Golden Dawn, Theosophists, psychical researchers, the Druid movement, and the Society of the Inner Light. The scene had already been set in the late 19th century, with the discovery of a purportedly ancient Blue Bowl. Rod Thorn’s account of this tells the tale: ‘The Victorian revival of Glastonbury as Avalon began here. A generation before Dion Fortune, a group of seekers played out a magical working in the landscape of Glastonbury, concealing and discovering a Holy Grail in the waters of an elusive well associated in legend with the goddess and saint Bride.’ (You can read the full story here.) The Spirit of Glastonbury In her book Glastonbury: Avalon of the Heart, the Inner Light’s founder, occultist Dion Fortune, tells us that there are three ways to arrive at Glastonbury: by road, through legend, or by less tangible means: ‘And there is a third way to Glastonbury, one of the secret Green Roads of the soul – the Mystic Way that leads through the Hidden Door into a land known only to the eye of vision. This is Avalon of the Heart to those who love her. The Mystic Avalon lives her hidden life, invisible save to those who have the key of the gates of vision.’ (p.1) Dion Fortune recognised, however, that there are different strands of interest running through the Glastonbury area, which sometimes come into conflict: ‘The Abbey is holy ground, consecrated by the dust of saints; but up here, at the foot of the Tor, the Old Gods have their part. So we have two Avalons, ‘the holiest erthe in Englande’, down among the water-meadows; and upon the green heights the fiery pagan forces that make the heart leap and burn. And some love one, and some the other.’ (p. 9) Alan Bain’s interest in Glastonbury remained firmly with its Christian heritage. He wrote on his website: ‘Glastonbury is regarded today by many as a place where, as Dion Fortune put it, "the veil is thin" [see below] …and it is this quality which imbues the site with its psychic reputation. In the eagerness for "New Age" developments and associated doctrines - mostly derived from theosophy - the essence of the legends, and possible psychic "facts" has become obscured by this same theosophical "New Age" overlay. But the mystery which is Glastonbury, and even its raison d'être is Christian, and bears little relation to so-called new age thinking…’ Dion Fortune was of course herself a Cabbalist, and as such was esteemed by Alan, especially as author of ‘The Mystical Qabalah’ which was the ‘set text’ for the early Group. Glastonbury was her part-time base, where she installed a large wooden cabin to serve as a guest house near Chalice Well, on the lower slopes of the Tor. (Benham p. 259). Although there are no known direct personal connections between the Group and Dion Fortune’s own ‘fraternity’, the Soho Cabbalists naturally paid close attention to Fortune’s written output, especially at a time where accessible and relatively modern works on Cabbala were scarce. And the milieu into which members of the Group stepped expectantly on arrival at Glastonbury, was largely created by the earlier interest of Dion Fortune and her followers, and by the mystical Christianity of Alice Buckton, who established a centre at Chalice Well. However, it was before the re-inflation of Glastonbury as a focus of New Age activity and the phenomenon of the Glastonbury Festival, which colour it today. In fact, Glastonbury has a long, fluid history, so portraying its ambience at a particular period of time can be tricky. I first visited Glastonbury around 1966, as a teenager; I begged my parents to let us stop off on the way home from a holiday in Torquay, as I had been influenced by notes I’d read about the town and its mystical history for my A Level text of Tennyson’s Morte d’Arthur. So I can at least recall from personal experience the difference between then and now, between the Glastonbury visited by group members from the late ‘50s to the early ‘70s, and the busy hive of mystical activity that it is today, not to mention the increased commercialism in shops selling crystals and wizards' cloaks! Back in the mid-20th century, it was a less visited, more overgrown, and somewhat more brooding place than in its present incarnation. ‘When history is in the making, as it is at Glastonbury, it is impossible to assess it at its real value. One can think of it only as it affects oneself…Glastonbury has ever been the home of men and women who have seen visions. The veil is thin here, and the Unseen comes very near to earth…’ (Fortune p.59). The Journey to Glastonbury Another factor to take into account is that it was far less straightforward to get there by road in the ‘50s and ‘60s. From London to Glastonbury is around 140 miles; the M5 and M4 motorways which we might use today, weren’t completed until the 1970s, so even travelling by ‘A’ roads could be very time-consuming. In holiday periods, hours extra were added on as traffic attempted to get to and from West Country seaside resorts. Dion Fortune describes the journey evocatively, romantically even, describing a gentle motor trip pootering through the different soils and terrains of England, over the heathlands of Hampshire and past the awe-inspiring Stonehenge, until finally entering the apple orchards of Avalon. But the reality for the post-war travellers of the Group – who often hitch-hiked anyway - was countryside buried under urban expansion, hold-ups with road works, and heavy traffic. It was a triumph for them finally to arrive at Glastonbury, but in a rather different sense to earlier seekers. They could not be sure of a warm welcome either. From the late ‘60s onwards, notices declaring ‘No Hippies’ began to appear in guest houses and restaurants. As a student at the time, my boyfriend and I struggled to find accommodation, and were finally directed by some guffawing locals to ‘Go down The Lamb! The Lamb’s the place for you.’ And indeed the rough-and-ready Lamb Inn took us in without demanding a marriage certificate or a haircut. Chalice Well too was guarded by elderly and suspicious ladies who did not welcome the youthful invaders of their sanctuary. The Visits As the Group began to branch into different Cabbala teaching groups, each leader took their own view of Glastonbury and passed it on in one form or another to their members. Stan Green recalls that in Tony Potters group: ‘Annually, at the Spring equinox we went to Glastonbury, acknowledged as a centre of esoteric power, to "recharge our batteries" as Tony put it.’ John Pearce, artist and fellow group member, was drawn back to Glastonbury on a number of occasions. The accounts he wrote of several visits, which he has shared for this article, show how Glastonbury could be a crucible for inspiring magical activities. It was a place where anything, it seemed, might happen, or could be encouraged to happen: (Returning from Cornwall in 1965) 'I continued eastwards to Glastonbury, by bus, train, hiking or hitch hiking. A Glastonbury shop window displayed a wicked-looking commando knife which I immediately bought, seeing it both as an ‘Excalibur’ and as a possible ceremonial accessory. Nowadays one should be arrested for carrying such an item, but at the time Boy Scouts still wore large sheath-knives, and I had no such fears. ‘In 1965 the great Abbey Barn, now a Rural Life Museum, was still in agricultural use. I asked no-one’s leave, and camped in the field next to it (now an extensive housing development). Admiring the barn itself, I saw it was cruciform, its four gables sporting the symbols of the four evangelists, approximately aligned to the cardinal points of the compass: the ox on the north gable, lion to the south, man to the east and eagle to the west, representing also the four elements and the four fixed signs of the Zodiac: ox, earth (Taurus), lion, fire (Leo), man, air (Aquarius) and eagle, water (Scorpio). On that basis I performed the Lesser Ritual of the Pentagram inside the barn, employing my newly bought ‘dagger’. Invoking or banishing? I can’t remember, but the overall consequence seemed efficacious and continued after my return to London.’ John Pearce’s interest had been kindled, and was further aroused when other synchronicitous events occurred: ‘In the early 1970s I made several more visits to Glastonbury...One which I made in 1970 was with Peter Westerman, who at the time had the use of a Ford Box van, his work being antique removals. We cooked and slept in the van, parked on Wellhouse Lane on the lower slope of the Tor. On the morning of our departure we found the vehicle wouldn’t start; there was no electric current. Fortunately the van was pointing down the gentle slope towards the town, so one steered and the other pushed, and many attempts at bump-starting were made en-route. Despite the helpful gradient it had been hard work. When we reached the edge of Glastonbury we parked and prepared to summon help. Before we could do so a diminutive bald gentleman came eagerly down his garden path from the nearest house and invited us in for morning coffee! This in itself seemed remarkable, and we had a pleasant morning of coffee, biscuits and chat, but more remarkable was that on returning to the van it started at the first attempt and gave no further trouble.’ The memoir of John’s visit at the Autumn Equinox, 1970, can be accessed below, with its account of encounters at the Tor and unusual lights flickering on its tower. It also reveals another aspect of the area, namely the dynamic tension between Glastonbury and the nearby city of Wells, with its famous Cathedral. Each has their own powerful atmosphere, and individuals may find it hard to withdraw from the pull of one to enter the other. The account also highlights the tussle within the hearts of some group members as to whether to fully accept the Christian path or not.

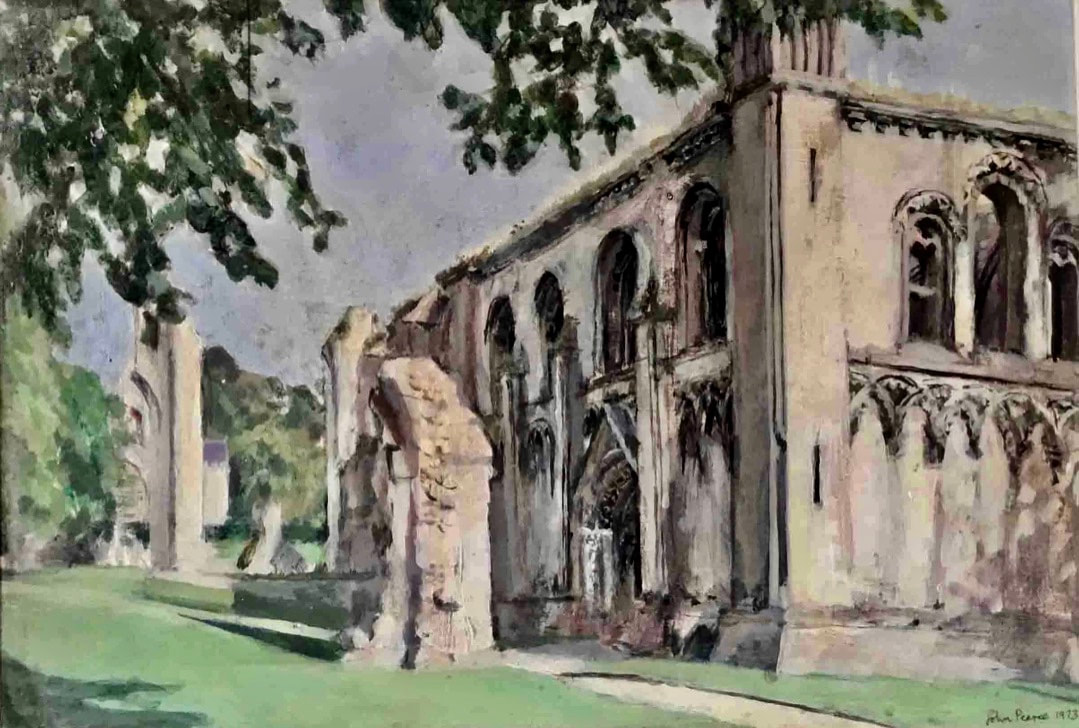

John Pearce’s account of the Spring Equinox in 1973 includes another tantalising description of strange lights on the Tor, this time seen through his guesthouse bedroom window: ‘I slept well, but woke suddenly in the small hours and saw St Michael’s tower silhouetted against a pre-dawn sky, with mercurial silver lights shooting vertically up at its edges like champagne bubbles. I went back to sleep - but I know I didn’t dream it. I assumed there was a scientific explanation. Next day I looked for evidence of fireworks, or any reflective features that could have caught headlights, but could find nothing to account for what I’d seen.’ During this visit, John also painted various Glastonbury scenes, and his picture of the Lady Chapel at the Abbey is shown below. Glastonbury wasn’t for everybody, and his fellow group member Stan Green became wary of its so-called enchantment, even though he acknowledged its visionary dimension, which he encountered on his first visit in about 1962: ‘I do remember a woman who was some kind of caretaker, showing us round. At the Well she said that she had seen in meditation, a passage going from the Well into the centre of the Tor.’ But the effect palled: ‘Our visits to Glastonbury were more like school outings with giggly children running up and down the Tor and in and out of the Abbey, than mature contemplatives. My fascination wore off after maybe the second or third visit.’ Glastonbury was tangential to the main work of the first Group and those which followed, but it certainly helped to illuminate some of that work. The kind of pathworking exercises and visualisations sometimes conducted in the groups gave a good training in using intuition and active imagination, and also encouraged sharp observation, and a neutrality which meant accepting visions and imagery as ‘interesting’, but not as concrete evidence. (Very useful in the imaginative climate of the town!) They had also learned something about ritual practice, which enabled them to respond to the situations which arose, and emotional charge of ‘the Glastonbury experience’. And the kind of synchronicities that tend to arise on visits to Glastonbury, were both a validation and an encouragement of the philosophies they had been practising. Glastonbury remained of great significance to Alan Bain, as he and his wife Margaret decided to move down to the area in 1963. Group member Norman Martin recalled how he and his wife also decided to leave their Clerkenwell home for Glastonbury. His wife went round Alan’s place in London to tell him, but only Margaret was there, who said, “Oh – Alan’s just gone down to Glastonbury, can you take his piano accordion and motorbike down with you?” Norman somehow managed to load them into his car, but the car broke down at Reading. In the end, however, he did get them to Glastonbury. As two other accounts in this blog also illustrate, journeys to and from Glastonbury could involve mysterious difficulties with transport! Perhaps visiting Glastonbury was more congenial than living in it. Within a few years, Norman moved up to Bristol to carry on his jewellery work, and Alan moved to Bath. Glyn Davies, the third key leader of the Group, and initiator of Saros, had a very particular relationship with Somerset and Glastonbury. Although he was born into a Welsh family in Llanelli, he spent nearly ten years of his childhood living with relatives in Somerset in the Highbridge area. This was due partly to family complications, and the fact that he had relatives fitted with the strong historic pattern of migration between South Wales and Somerset, because of the shipping via the Bristol Channel. As Glyn wrote in a letter in 1968, when asked to give his former addresses: ‘I can start from the age of nine or ten years. No. 1 Carters Cottage, Stretcholt, Pawlett, Somerset. No. 2 11 to 18 years, 58 Church Street, Highbridge, Somerset.’ (Images below are from a recent sale of Carter's Cottage, Stretcholt) By the time I met him in 1970, he had frequented Glastonbury for many years. This was only about twenty miles from the Somerset haunts of his youth, and quite probably he had visited it before he even came into contact with Cabbala while serving in the RAF from 1947-57. He continued to feel a link with Somerset as a whole, and rented a little cottage in the Mendips to write his novel ‘Circum’ around 1966. The novel is partly set in that Somerset countryside, and the coastal resort of Burnham-on-Sea which Glyn knew so well. And in 1967 he took Gila, his wife-to-be, to show her the Abbey, and to climb the Tor. As he was to some degree a native of the area, his view was almost certainly different to those coming to Glastonbury as expectant pilgrims, and he probably had a more realistic take on the Glastonbury mix. The Somerset Levels also have elements of poverty, a dislike of incomers, and their own uproarious customs like the annual Carnivals, which take place as the darker months of autumn descend and are celebrated in the traditional way, with plenty of drink and flashing lights! Glyn cherished the mysticism of Glastonbury, but understood its place in the Somerset landscape. He told me that he had once slept for three nights in a row on the Tor: ‘And then I understood what Glastonbury is all about’. ‘So what is that?’ I asked him, but he would never tell me! He did however also say on another occasion that it was ‘cloud cuckoo land’, not necessarily in terms of fantasy, but as a place of dreams and a melange of mystical aspirations. ‘You can feel that cloud descending when you’re still a few miles out of the town.’ He was very familiar with the site of Dion Fortune’s house there; on a visit in 1971, he took my husband and I to see it immediately we arrived in the town, because he loved the view from there so much. We had driven down in our little ex-post office van and the three of us embarked on a ‘magical mystery tour’ of the West Country, of which Glastonbury was the first port of call. On the way back, we detoured via Cheltenham to meet magician and writer Bill Gray, another acquaintance of his. Glyn also solved a problem with our van that even the garage hadn’t been able to fix. It was in the habit of slowly juddering to a stop, and wouldn’t start again for twenty minutes or so. When this happened on our trip home, Glyn walked around the car thoughtfully, then asked, ‘Do you have a pin?’ I found a safety pin, he did something around the back, and the van started up again beautifully and never misbehaved again. ‘Airlock,’ he said. ‘Just gave it a couple of pricks.’ We’d bought a new rubber petrol cap a few weeks before, and it was forming a vacuum in the pipe. He had, after all, been classed as a ‘fault finder’ in the RAF radar department! Did Glyn have any special contacts in the Glastonbury area? His own teacher came from Yorkshire, but during the years that he began to practice Cabbala, he made it his business to make many contacts in esoteric circles, and to understand how they worked. One possible source or contact has come up through our more recent research, which is Ronald Heaver who presided over the Sanctuary of Avalon. He was a significant figure in the area at the time, whose approach was to some extent aligned with ours; he also had a wide network of contacts. It seems very possible that Glyn could have known him, and an account of Heaver and his Sanctuary can be found below.

Winter Solstice at Glastonbury, 2003. (Photo Cherry Gilchrist) Winter Solstice at Glastonbury, 2003. (Photo Cherry Gilchrist) Conclusion This is just a glimpse of how members of the groups related to Glastonbury, and is certainly only just a snapshot of the history and significance of the place. My brief here has been to describe what we know of members’ experiences, from material to hand, and to show something of the connection between the town and the work of the groups. No one from these groups, as far as we are aware, remained permanently in Glastonbury or even lived there a long time; in some ways the Glastonbury ethos was counter to the more clear-sighted attitude of the groups, where synchronicities and visions are considered meaningful, but are not ultimately the goal of ‘the Work’. Cherry Gilchrist References Glastonbury: Avalon of the Heart – Dion Fortune. First published in 1934, this is an evocative reflection upon the town and its significance, as she knew and experienced it. The Avalonians - Patrick Benham – an excellent historical account of esoteric activity and lines of work in the area A Glastonbury Romance - John Cowper Powys. A long, complex but beguiling novel which captures much of the spirit of Glastonbury, and the different strands running through it. Set in in the 1930s. Circum – W. G. Davies (published privately) – a novel with an esoteric underly; each of the 22 chapters is based upon a Tarot card. Set partly in Somerset. Acknowledgements With sincere thanks to John Pearce for sharing his memoirs and art, Stan Green for his recollections, Gila Davies (Zur) for permission to post the photograph of her visit to Glastonbury. Also to R. J. Stewart for inviting me to visit to his current-day Sanctuary of Avalon on the side of the Tor, and much interesting discussion and correspondence about Ronald Heaver and other stalwarts of Glastonbury.

1 Comment

4/11/2020 04:03:18 am

Thankyou for putting this together. The Tor has held a special meaning for me for many years.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsArticles are mostly written by Cherry and Rod, with some guest posts. See the bottom of the About page for more. A guide to all previously-posted blogs and their topics on Soho Tree:

Blog Contents |

||||||||||||

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed