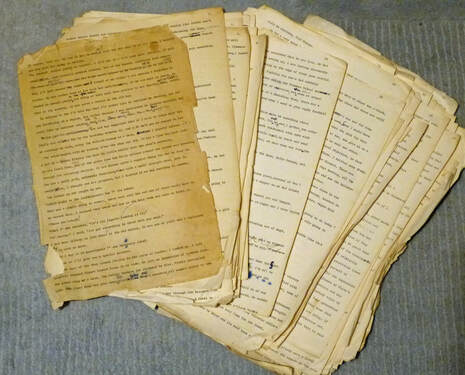

A battered copy of Glyn’s novel Circum lies in one of my study drawers. The loose foolscap pages are yellowed by tobacco smoke, and worn thin and ragged at the edges from frequent handling. It is typed, but here and there amended by hand. Some of the pages are scrawled over with notes and diagrams, most probably the first thing that came to hand when Glyn had to jot down an idea in a hurry, or wanted to explain something to a visitor who’d come with serious questions. My connection with Circum goes back to the early ‘70s, when Glyn thrust a copy at me to read, and then to type up for him, as a paid task. It went through several incarnations, with several typists, the final version as a dot-matrix print-out , probably in the early ‘90s. Glyn was by his own admission a ‘jack of all trades’ or ‘generalist’ who could and did attempt almost anything. He was variously a jeweller, an accountant, a salesman of babywear, a book dealer and a radar fitter, to name some of his occupations. He also decided to be a writer – not as a literary author, but as an exponent of ideas and a generator of stories with a mythical flavour. Circum was his one and only novel, written in the late 1960s. In one sense, it’s a traditional boy-meets-girl, then-meets-another-girl kind of story. In another, it’s an account of entering a spiritual path. And thirdly, it’s a fascinating snapshot of life in post-war Britain. According to Glyn, it was partly (but only partly) autobiographical. And according to one of the early group members (Norman Martin, who trained Glyn in jewellery-making), Glyn went on a kind of self-imposed retreat to write the book. He rented a tumbledown cottage for a few months in the Mendips. ‘It was just a pile of stones…,’ Norman recalls. Glyn used his time in the Mendips to try out caving, something that features in the novel. He liked to experience what he was going to write about. The novel has twenty-two chapters, and Glyn told me that each one is based on a Tarot card (there are twenty-two cards in the Major Arcana of the Tarot). But which is which? Ah, that’s left to the reader to discover! And my guess is as good as yours, except for one chapter which Glyn did tell me represents the Empress. After Glyn’s death, I decided that it was worth getting Circum into print. Other books of Glyn’s had been published, but not this one. With the permission and help of his family, I prepared a print-on-demand edition. And editing it was quite a task! Glyn did not bother with the finer points of punctuation or consistency, even though he was a good wordsmith. I found myself having to decide whether the hero was really heading for the docks at Liverpool, as first stated, or Southampton, as on the next page. But it was a rewarding task, and the resulting copies were ordered by well over a hundred of his acquaintances. Now plans are being considered to produce an electronic version, which could be made much more widely available. Towards the end of Circum, Charles Hawton, the hero, begins to forge a proper relationship with Fenella, a girl from the East End of London. Fenella is a chirpy Cockney sparrow, sometimes frivolous, but the reality of the understanding they have at a deeper level begins to emerge. Read on.....the extract follows below... ‘And there’s me. When I was a little girl, I used to dream of knowing everything, and I still just want to know. Mum says I’m a bookworm, but I’m not really. Sometimes I like books, even books on astrology.’ She laughed out loud.

I remembered John Britten’s shop, and then I was laughing too, a little ruefully I must admit. ‘Anyway,’ said Fenella, ‘I always wanted to talk proper, and I used to mimic the teachers and the radio-announcer and the Methodist Minister. Mum wasn’t religious - she used to send us to Sunday school because, she said, “Some of it’s just good common sense.” She’d ask us what we’d been told there. Dad was a Mason, I think, though I’ve never seen any of his paraphernalia. At school I did well at art, and went to art college, but I didn’t think I’d ever be any good, so I took a secretarial course. The rest you know.’ What did this matter? Here was reality. The trappings were not important. She tended to seek out well-known people, and her culture was a little stiff and pompous. She dressed very fashionably and could become cockney shrewish, but she herself left me feeling easy. The layers over the essential Fenella just did not matter. It is curious that where there is love, there is no need to forgive foibles and habits. They just don’t really intrude. I tried to say something of this to her. She grew thoughtful. ‘Sounds silly, doesn’t it, but I feel as though I wear many skins, like an onion. Oh I dart around, and talk of clothes and I gossip, but that’s not me you know.’ This caused me to smile. I of all people should surely know this. ‘Do you think that you are anything particular?’ I asked. ‘No, the “me” doesn’t change. The things about me do - my clothes, accent, how I react - but me, I’m still the same as I was as a little girl, playing in the back yard and climbing on the wall to wave to the trains. Or even meeting you for the first time.’ My mind flashed back to the bookshop which I saw with a strangely familiar clarity, as if it would be that way for always. She stood there, looking at me. I was sitting behind a roll-top desk covered with books. Behind me were shelves with valuable stock, dusty volumes, leather bound and embossed, and with that slightly acrid smell, that probably comes from fish glue and animal hide. The shop door opened and this smiling small waif stood there and tentatively asked, ‘Do you stock books on astrology?’ I just gestured to her, and went on reading. Then some gateway opened, and my own memories began to surface. Standing in open-mouthed astonishment because the little bird I held in my hand, which was caught by my grandfather in his netting trap, was pecking me furiously. Drawing and colouring an apple, a glorious red shot with green and fat like bursting, when I was only four. A new suit I didn’t want to wear. My parents upset because I wanted to do everything for myself. Guiltily selling a pet jackdaw so that I could buy a model train that worked. It was brass, with a space for a real fire which could get the steam up. Sitting in the dust by the roadside, making imaginary castles while people in clogs and supply carts passed me, coming in from the country. My feeling of frustration because I never asked the right questions or, if I did, people didn’t understand me. The eternal moments when I stood on a bridge and watched the fishes swim. And then, behind these memories, another place where I lived a different life. I think that children really do live in another world, next door to this world but maybe only half an inch away, where they make kings and oceans, ships and savages. I told Fenella what I thought. She said delightedly, ‘Yes, yes, and you used to make little worlds and big worlds and have all your own stars. You didn’t have to believe in any of them - they were just there, and when you finished, you could put them away and bring them out again, like toys from the cupboard. ‘I used to have a friend; he was an eagle. He came from a high, high mountain far away, and he could fetch me anything I liked. We talked together before I could talk to Mum and Dad. But he went away one day, and I began to grow up.’ (Circum pps 135-7) Cherry Gilchrist

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsArticles are mostly written by Cherry and Rod, with some guest posts. See the bottom of the About page for more. A guide to all previously-posted blogs and their topics on Soho Tree can be found here:

Blog Contents |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed