|

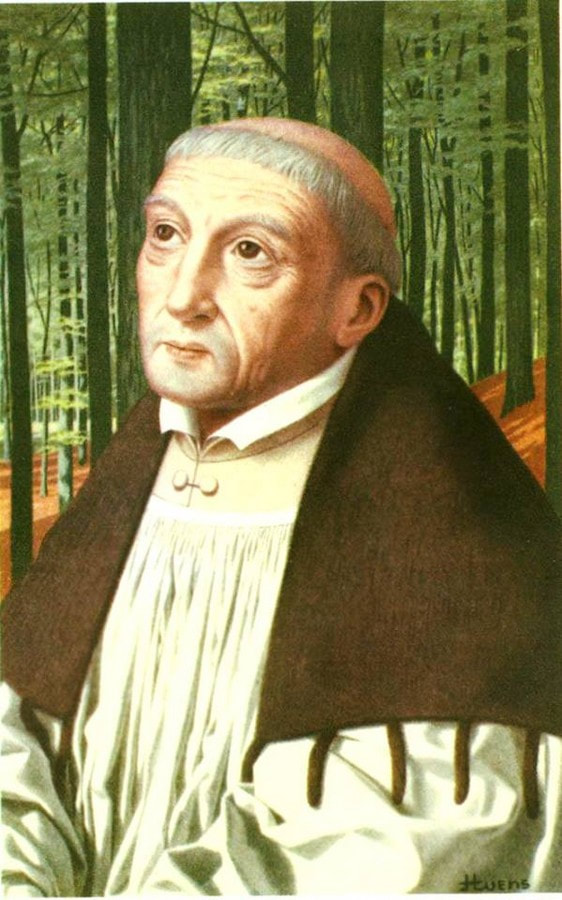

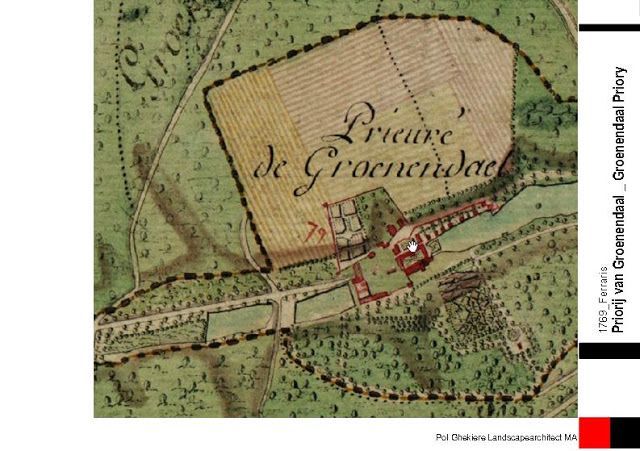

‘The Society of the Common Life’ The early Kabbalah groups in Soho and their successors elsewhere were often run under this name. Why so? And where did the name come from? Although we don’t have all the answers about how it was introduced into the groups, it was always said that our lineage was descended through the original Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. This was a movement initiated in the 14th century in the Low Countries of Europe, to allow men and women to practice a Christian ‘mixed life’ of work, study and contemplation in a communal fashion, without taking holy orders. In the first part of this account, I’ll set out its history and what we know of the practices of the Brothers and Sisters, plus the significance of Common Life itself. Then in the second part, I’ll return to questions of how and why this lineage was affirmed in our groups. Ruysbroeck The story starts with the 14th century Christian mystic known as John of Ruysbroeck (also spelt Ruysbroek, Ruusbroek), who was the inspiration for the founding of the ‘Common Life’ movement. His written works are still renowned today, and are imbued with a deep understanding of the stages of spiritual progress and the levels of contemplation. (For a series of quotes from his writings, see here ) Ruysbroeck was born in 1293-4, in a village of the same name, situated in what is now Belgium. His mother was a single parent, his father unknown. He left home when he was eleven, to live in Brussels with his uncle Jan Hinckaert, a priest, and his colleague Frances von Coudenberg. As the years went on, they formed a small and closely-bonded spiritual group, described as ‘a veritable mystical association’. Ruysbroeck was also formally educated at the Latin schools in Brussels, and in 1317, he was ordained as a priest. But in 1343, he and his two fellow seekers applied to take over the nearby forest hermitage at Groenendaal, in rural isolation. Here they built a chapel, and tried to live a life of quiet contemplation. However, they were apparently plagued by the duke’s huntsmen, and their excessive demands for hospitality. For this reason, they eventually decided to place themselves under the rule of St Augustine, as ‘regular canons’, which gave them some protection against intruders. Ruysbroeck and Kabbalah Many visitors sought Ruysbroeck out in the hermitage, though for better reason than the huntsmen: asking for spiritual guidance, and sometimes to join the order. Ruysbroeck had begun writing mystical texts before he left Brussels, and was already renowned for his wisdom and insight. As already mentioned, his books are still revered today as classics of Christian mysticism. They are a combination of offering a structured approach to stages of spiritual development, but also of showing the way to the transcendent, soaring into the realm of what he called the ‘wayless’, leaving behind both images and explanations. It’s clear from his writing that he was informed both by his own experience, and by drawing upon some kind of existing philosophical framework which he then developed. The exact sources remain unverified, though they probably include Meister Eckhardt (who may even have been an acquaintance of Ruysbroek’s), along with Neo-Platonic teachings, and quite possibly Kabbalah, which could have been transmitted via the 12th and 13th c. Spanish Kabbalistic schools. His use of symbolism, his structuring of spiritual experience, and his specific description of the Seven Gifts of the Spirit, certainly accord more closely with a Christian form of Kabbalah than with Neo-Platonism. This is expanded in his major work, The Spiritual Tabernacle, his magnum opus in terms of symbolism. Gerard (Geert) Groote (1340-1384) It is Gerard Groote of Deventer (now in the Netherlands) who then takes the story forward into what was to become the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. In 1377, Groote came to Groenendaal in order to visit Ruysbroeck, and stayed there for nearly two years. The two men had never previously met, but legend has it that Ruysbroeck seemed to be expecting Groote, and greeted him like an old friend. Whatever the truth of legend, (and there may well be some), the transmission of some kind of spiritual inspiration from Ruysbroeck to Groote is generally accepted by historians. Groote came again in 1381, just before Ruysbroeck died, as a very old man in his late 80s, and Groote himself died only three years later, while still in his 40s. Between the two visits, Groote initiated a whole new course of action. He opened his house to those poor women of Deventer who wanted to lead a spiritual life, and (probably with his male follower Florence Radewijns), founded houses for the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, and what were to become very important part of their work - schools for children. The Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life from then on became known as educators, and the network of their schools spread throughout Europe. Groote himself became known as the founder of the ‘Devotio Moderna’, a simpler, more direct and pious form of worship than had been practised in that era, and a precursor of the Reformation. Deventer itself was a well-established trading port on the River Ijssel, and became a member of the important Hanseatic League, a trading and defence guild for merchants. Its Latin School was established in 1300, and the town became associated with both education and, slightly later, with printing. It seems a natural home for the first efforts of the Brothers and Sisters to study, copy manuscripts, and educate. Groote’s old home is now a Museum named for him. Gerard Groote's old house, now a Museum. These figures probably represent a Sister and Brother of the Common Life. Although Ruysbroeck and Groote seem to have been very different types of men – Ruysbroeck more mystical and compassionate, Groote zealous and upright in his moral resolve - the link between them was strong, and the key concept which united them was that of Common Life. So it is this that I will now move on to. The term Common Life To him now is shown the Kingdom of God in a five-fold manner. Since the external, sensible kingdom is shown to him, in the same way too the natural kingdom, the kingdom of scripture, the kingdom of grace above nature and scripture, and finally the divine kingdom above grace and glory is also shown. For to have all these things clearly and lucidly known and ascertained, is called common life. The Kingdom of the Lovers of God – John of Ruysbroeck, Chap 37 Ruysbroeck’s description of Common Life here is key to understanding its meaning, both for him and in a more outward way, for members of Groote’s Common Life movement. Its aim is to unite practical life, learning and study, and contemplative experience of the divine. In Ruysbroeck’s terms, it is a precise path of knowledge, with five levels to its ‘kingdom’: the outer world of the senses, the ‘natural’ level of nature and life forces, the level of sacred learning, then that of grace, and ultimately the divine and formless realm beyond that. The Common Life movement did practice spiritual exercises – more about this further on – but their main emphasis was on uniting action and contemplation while living a ‘common’ life together. The Brothers and Sisters shared their worldly goods and lived communally, aiming to unite outward work and acts of charity with practices of meditation and prayer. They also placed emphasis on the individual’s own relationship with God, refuting the notion that it could only be offered via a priest or by taking holy orders. Historically, this was a time of arrogance and corruption among the priesthood and monastic orders, and this stance of The Common Life movement prefigured and indeed influenced the Reformation, including its leading figure of Martin Luther. The Path to the Mountain The Brothers and Sisters sometimes took holy orders, however, mainly for the kind of reasons that Ruysbroeck and his followers did – to avoid persecution of one sort or another, and so that they could work freely towards their goals. The Congregation of Windesheim, founded in 1386, was one such development, of which the famous mystic Thomas a Kempis was a member. He is best known for his book The Imitation of Christ, which ‘is perhaps the most widely read Christian devotional work next to the Bible, and is regarded as a devotional and religious classic. Its popularity was immediate, and it was printed 745 times before 1650.’ (see more here) The followers of the Common Life also produced various written works and teachings over the years, and although these vary considerably with individual authorship and practices of different ‘houses’, there are some strong themes which emerge. One of particular interest is how they described the journey towards God as that of finding our path back to the holy mountain, from our exile in the valley. Gerard Zerbolt, one of the first members of the congregation of Windesheim, described how we have forgotten that the mountain is our true home, and have lost our way in a valley located in a distant land. Therefore, he says, “a great labour” is needed in order to return. This is more than a pious sentiment; it is clear that spiritual exercises were practised by the Brothers and Sisters, to undertake this ‘labour’. Note that this corresponds well with the term ‘the Work’, as used by the Kabbalah groups, to define the task of acquiring knowledge and achieving self-transformation. Although there are other sources for this, such as ‘the Great Work’ of alchemy, and ‘the Work’ of students of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, nevertheless it has a strong correspondence with the practices of the Kabbalah groups, along with the notion that we are on a path of ‘return’, climbing the ladder of the Tree of Life. And as for the ‘Holy Mountain’, we will meet this again in a forthcoming blog on the Dutch Astrology tradition, connecting to the Soho Tree lineage. The Schools of the Common Life The chief ‘outer’ work of the Brothers and Sisters began by taking paid work copying books and manuscripts, but then evolved into the field of education. Many schools were established and maintained under the tutelage of the Brothers of the Common Life over the following hundred years or so in the Low Countries, Germany and even further afield. The influence of these schools was enormous. Erasmus was one of their noted pupils, as were Luther and Nicholas of Cusa; even a future Pope (Adrian IV) was trained there. Roles and Gender within the Brethren of the Common Life In the Brother and Sister Houses, goods were held in common, and a common way of life was practised by all. However, Groote respected people’s individual gifts, and persuaded individuals to find the best occupation for their spiritual progress. For instance, he encouraged John Cele, the head of the school at Zwolle, to stay in his job rather than take holy orders. Women were – more or less – on a par with men; houses tended to be single sex, though there are records of at least one married couple living there. However, Groote himself seems to have been wary of women. Although he helped many women, first of all by opening his own house to poor single or widowed women, he avoided contact with the female sex as much as he could, and saw marriage primarily as a means of procreation and controlling lust. The Way of the Common Life But however effective the Brothers and Sisters were in living a pious and productive outer life, they considered the inner path to be of supreme importance in fostering ‘the common life’. I’ll now give a summary of what appear to be the main ingredients of this aspiration to attain ‘common life’. Five-fold kingdom The work for both Ruysbroeck’s and Groote’s followers combines contemplation and action. As we’ve seen, according to Ruysbroeck it demands an effort to attain knowledge of the ‘five-fold’ Kingdom of God, in their forms of matter, nature, scripture, grace and divinity. All five parts of this kingdom must be experienced to attain to this ‘common life’. Members of one body It corresponds (to an extent) with the view that all men are members of Christ’s body, the One Man, which can perhaps be likened to the perception of Adam Kadmon, the Great Man, in Kabbalistic terms. The individual’s connection to God It defies any monastic claim that man can only come to God through a member of a spiritual hierarchy, in particular via priest, ordained monk or nun, or that this is a path only for males. Self-perfection is possible for a human being. It is our birthright, and even our duty, to seek the ‘impress’ of God within our hearts. Conduct The person on the path should be humble, kind to others, abstemious but not austere. Life should be a mixture of contact with the world, and retreat from it. It is sometimes described within the brother-and-sisterhood as the way of Mary and Martha, both aspects being important. In the common life, an individual should practice both an inner and an outer trade. If you trade on the street, you must also service your ‘inner workshop’ The need for spiritual exercises Exercises and special actions are necessary for this. According to what we know of the practices of the Brothers and Sisters, these include:

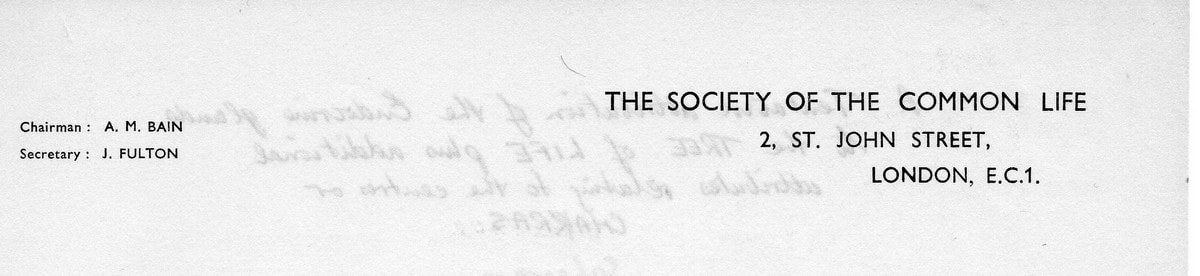

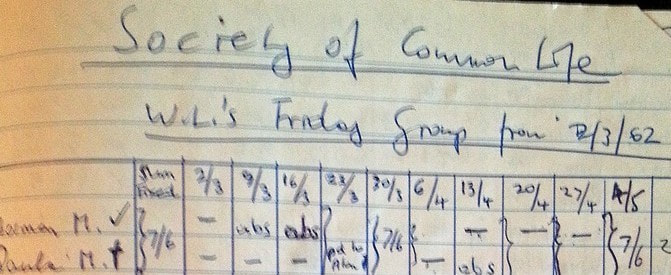

Some practices may involve an advanced level of contemplation, whereas others require outward acts of remembrance: the Brothers, for instance, ‘paused and prayed whenever they heard the church bells ring’. They also sought to “prevent” each activity with a brief prayer to clarify their direction’. (Perhaps this is something similar to the Gurdjieff ‘Stop’ exercise?) Examples of these practices can be found in the writings of Ruysbroeck, Groote and his followers, Erasmus, Thomas A Kempis and the English Platonists, though much more remains to be done to extract them from the texts. Some are stated openly, whereas other methods may be couched in descriptions of mystical experience which seem to suggest specific exercises. So it’s clear that both Ruysbroeck and the followers of Groote, ie the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, knew a range of exercises which involved both body and mind, and which could be practised as contemplative or within the context of active life. It also seems very likely that all this was underpinned by a structured mystical cosmology, perhaps a version of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. The quotes below, with which I end this account, illustrate some of these points, and also the sense of what ‘common life’ meant to these our spiritual ancestors. But first I’d like to return to the connection between the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life and the Soho and subsequent groups. The Society of the Common Life A number of core Kabbalah groups in this ‘Soho Tree’ tradition have been called ‘The Society of the Common Life’. These include the first one founded by Alan Bain in the late 1950s, and offshoots such as the broader-based Kabbalah meetings held in Cambridge from 1969 under the aegis of Glyn Davies and Lance Cousins. Acknowledgement is also given by teacher Warren Kenton , who dedicated one of his principal books, Adam and the Kabbalistic Tree, to the Society of the Common Life (1985 edition). There were also variants of this – The Society of the Hidden Life (leader Tony Potter), and the Society of the Inner Life (leader Robin Amis). Below are examples of this - notepaper heading used by Alan Bain, and a notebook of Walter Lassally's recording subscriptions paid by group members in 1962. In the group to which I belonged, we were told that our lineage had descended through the original Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. Like any family tree, there are different branches, and it may be that this was just one line which blended into the particular tradition of Kabbalah which we inherited. This particular strand of Kabbalah had apparently reached Britain from the Low Countries just after World War One, and was passed down very much on a one-to-one basis until the expansion of groups in the 1950s. However, there is one stray fact which leads to more questioning. There was also some use and acknowledgement of the name in the Study Society and its sister organisation the School of Economic Science (SES). It’s also reported that a few members of these organisations visited a descendant of the original ‘Common Life’ house in Deventer. As there was an overlap in the 1950s and 60s between the Kabbalah groups and SES, we cannot be sure in which context the initial introduction of the Society of the Common Life arose. Although the name has had specific applications in different groups, the universality of its overall meaning has provided a very useful gateway, indicating that religion need not divide us, and that anyone from any faith or none will be welcome to study. By the same token, its a strongly-held principle that the name does not belong to any one person or movement; no one can lay claim to it. Perhaps, rather than pinning down the history of the name too specifically, it’s more fruitful to make use of its implications. The Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life opened the way to an individual spiritual path, which has served us right into the modern age. It is one which is not dominated by authority figures (or gurus), which recognises the commonality of humankind, and also the necessity of combining meditation with everyday life. Common Life Texts

Although some of the texts are hard to find, dense to read, and not always well translated, there is still much to appreciate. On a personal note, I began reading the writings of John of Ruysbroeck in the early 1970s, and have dipped into the history of the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life ever since, though not with scholarly application. But even if I have not worked as a scholar in this field, everything I present here comes from reliable sources. Exercises for ‘self-remembering’ and awareness With the left eye gaze at the transitory, and with the right the heavenly. Thomas a Kempis It was said of John Hatten, the cook’s servant at Deventer, that “Although with Martha he was attending in outward things, yet with Mary he was continually directing his attention towards those things which were needed and longed for ardently within, as much as he was able.” ‘The Brotherhood of the Common Life and its Influence’ - Ross Fuller (p112) The spiritual exercises and meditations of The Brotherhood of the Common Life were concerned above all with this movement between outer and inner life. The Devotionalist Rudolf Dier de Muden used to say: “My years are many and there is scarcely any fruit of them in me; pray therefore for me, that at least in my decrepit age I may be able to recollect myself.” ‘The Brotherhood of the Common Life and its Influence’ - Ross Fuller (p130) While I am seeking or doing anything outwardly, grant me grace to remember myself inwardly. William Peryn 1557 Quoted in ‘The Brotherhood of the Common Life and its Influence’ - Ross Fuller Now understand this: God comes to us without ceasing, both with means and without means, and demands of us both action and fruition, in such a way that the one never impedes, but always strengthens, the other. And therefore the most inward man lives his life in these two ways: namely, in work and rest… Thus the man is just; and he goes towards God with fervent love in eternal activity; and he goes in God with fruitive inclination in eternal rest. ‘The Adornment of the Spiritual Marriage’ Chap 65 - John of Ruysbroeck Instructions for meditation and contemplation Now if the spirit would see God with God in this divine light without means, there needs must be on the part of man three things. The first is that you must be perfectly ordered from without in all the virtues, and within must be unencumbered, and is empty of every outward work as if he did not work at all: for if his emptiness is troubled within by some work of virtue, he has an image; and as long as this endures within him, he cannot contemplate. Secondly, he must inwardly cleave to God, with adhering intention and love, even as a burning and glowing fire which can nevermore be quenched. As long as he feels himself to be in this state, he is able to contemplate. Thirdly, he must have lost himself in Waylessness and in a Darkness, in which all contemplative men want in fruition and wherein they never again can find themselves in a creaturely way. In the abyss of this darkness, in which the loving spirit has died to itself, there begin the manifestation of God and eternal life. ‘The Adornment of the Spiritual Marriage’ Chap 65 - John of Ruysbroeck ‘If… This good man would become an inward and ghostly (ie spiritual) man, he needs must have three further things. The first is a heart unencumbered with images; the second is spiritual freedom in his desires, the third is the feeling of inward union with God.… Further, you must know that if this ghostly man would now become a God-seeing man, he needs must have three other things. The first is the feeling that the foundation of his being is abysmal, and he should possess it in this manner; the second is that his inward exercise should be waylessness; the third is that his indwelling should be divine fruition.’ ‘The Sparkling Stone’ - John of Ruysbroeck The three rills This set of instructions for meditation written by Ruysbroeck hints at a practice which might have involved using the breath in certain ways to experience the ‘three rills’ of cosmic flow. At any rate, it suggests a profound form of contemplation, with distinct stages. Now Christ says inwardly within the spirit by means of this burning brook: GO YE OUT by practices in conformity with these gifts and with this coming. By the first rill, which is a simple light, the memory has been lifted above sensible images, and has been grounded and established in the unity of the spirit. By the second rill, which is an inflowing light, understanding and reason have been enlightened, to know the diverse ways of virtue and practice, and discern the mysteries of the Scriptures. By the third rill, which is an inpouring heat, the supreme will has been enkindled in tranquil love, and has been endowed with great riches. Thus has this man becomes spiritually enlightened; for the grace of God dwells like a fountainhead in the unity of his spirit; and its rills cause in the powers and out flowing with all the virtues. And the fountainhead of grace ever demands a flowing back into the same source from whence the flood proceeds. ‘The Adornment of the Spiritual Marriage’ Chap 38 - John of Ruysbroeck Books D’Aygalliers, A. Wautier - Ruysbroeck the Admirable (Original French edition 1923; English translation J. M. Dent 1925) Engen van, John (ed) – Devotio Moderna Paulist Press, New York 1988 Fuller, Ross - The Brotherhood of the Common Life and its Influence (State University of New York Press, 1995) Post, R. R. – The Modern Devotion (Studies in Medieval and Reformation Thought) Brill, Leiden 1968 Underhill, Evelyn – Ruysbroeck Selected works usually available by John of Ruysbroeck: The Adornment of the Spiritual Marriage The book of Truth The Sparkling Stone The Kingdom of the Lovers of God The Twelve Beguines Articles ‘The Quiet Revolution’, Robin Waterfield in Gnosis magazine, Fall 1992 ‘The Devotio Moderna’, Tony James (unpublished) Blog by Cherry Gilchrist The account above is a shorter and revised version of one which I wrote in 2018, for limited circulation among the current network of Saros and group. You are free to use the material, but please quote Soho Tree website (www.soho-tree.com) and Cherry Gilchrist as the source.

5 Comments

Briji Waterfield

6/1/2021 10:07:26 am

Great article!

Reply

7/1/2021 05:59:42 pm

Very interesting. Thank you. I wondered in various respects, and the nore I look the more I see parallels, about the influence of the Spiritual Exerises of St Ignatious of Loyola. Any hints of that in the research? Perhaps it would be odd if there weren't...

Reply

Cherry Gilchrist

8/1/2021 07:58:36 am

Hard for me to say - Loyola came after the main thrust of Ruysbroeck's and Groote's Common Life movement and I haven't studied his work, though have heard of it of course. However, the faithful (?) Wikipedia says: 'After recovering from a leg wound incurred during the Siege of Pamplona in 1521, Ignatius made a retreat with the Benedictine monks at their abbey high on Montserrat in Catalonia, northern Spain, where he hung up his sword before the statue of the Virgin of Montserrat. The monks introduced him to the spir'itual exercises of Garcia de Cisneros, which were based in large part on the teachings of the Brothers of the Common Life, the promoters of the "devotio moderna".'

Reply

Paul Maiteny

9/1/2021 08:37:01 pm

Thanks Cherry. I forgot to think about the dates! So it would have been the other way round, Brothers of the Common Life influencing Ignatius.

Reply

10/1/2021 08:43:20 pm

A very interesting and informative account. The Common Life does appear as a linking ethos recognisable in groups and spiritual pathways which may or may not be historically linked.They acknowledge the same dimensions of human reality. I'll certainly be re-reading this article, so many thanks for such a lucid introduction.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsArticles are mostly written by Cherry and Rod, with some guest posts. See the bottom of the About page for more. A guide to all previously-posted blogs and their topics on Soho Tree can be found here:

Blog Contents |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed