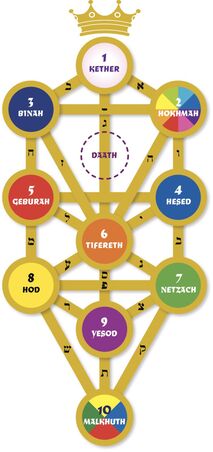

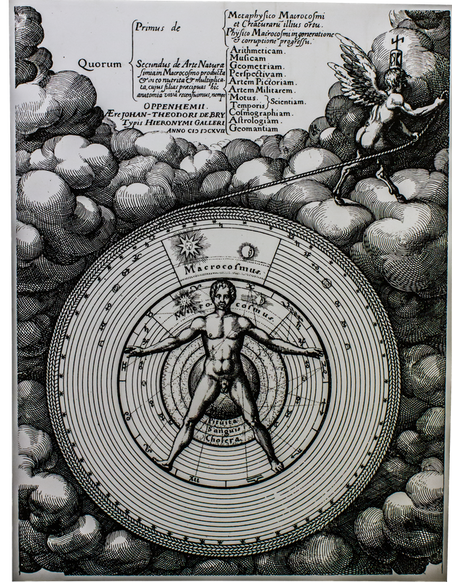

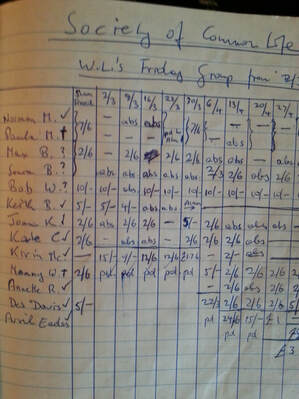

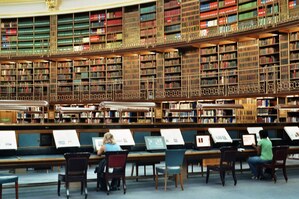

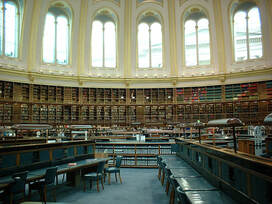

A typical working diagram of the Tree of Life (not from 'the Group' itself' with names of Sefiroth, Hebrew letters and colour attributions A typical working diagram of the Tree of Life (not from 'the Group' itself' with names of Sefiroth, Hebrew letters and colour attributions From the coffee bar to private groups The gatherings of budding Cabalists in Soho cafes were only the outer face of ‘the Group’, in the late 1950s. Those who showed a serious interest in pursuing it further would be invited to a private meeting, in someone’s flat or a rented room. Keith Barnes recalls: ‘Everything was kept very quiet, and it was very hard to find out anything. Even the existence of the group was hidden.’ Then, one day in the coffee bar, someone slipped him a piece of paper with date, time and address on it: ‘Turn up if you want to know more.’ He did – the meeting was at the flat where Walter Lassally lived, and who he already knew, and to his surprise there were several other familiar faces there from the Soho scene, plus leaders Glyn Davies and Alan Bain. Lionel Bowen adds: ‘I believe the Group met in Walter’s flat before I joined but we juniors were kept separate from the others until we were judged to be ready.’ The main tasks were to work on the Tree of Life, and, correspondingly, on one’s inner being. The group studied Kabbalistic attributes, including numerology, astrology, Tarot, and the colours associated with Sephiroth on the tree. The ‘text book’ used was Dion Fortune’s Mystical Qabalah, but whereas this provided a good point of reference, the emphasis was always on personal experience and observation. In the earliest period, members were also assigned to ‘grades’, corresponding to the level of the Tree which you had attained or had awoken in yourself. Under Alan Bain’s tuition, the aim was often stated more generally as ‘to pass through the Veil’. It was a combination of the mystical and the practical. Walter Lassally recalled that ‘Group sessions were very practical, but they were intended to push you up the tree and get you through the veil. And I remember very distinctly an occasion when Alan considered that I had passed through, after about two or three years of study. It’s a spiritual journey, with realisations on the way.’ As Walter pointed out, the formation of the Tree itself helps this process: ‘If you associate Netzach with emotion, and Hod with intellect, this is very helpful, and shows you that intellect should balance emotion, but it shouldn’t control emotion.’ Walter also ran groups of his own after a few years, under the aegis of the Society of the Common Life. This taking on of responsibility has been a feature of the tradition; many of us who joined in the 1970s and 80s were soon encouraged to set up groups, rather than waiting decades to become recognised teachers. ‘The spirit of knowledge’ – or even ‘the Common Life’ as a symbol of the mind of humanity - is considered to be the guiding principle of the group, so that a group has a leader rather than a guru. Numbers were kept small – the old saying is that it takes seven to create a group with its own soul and dynamic, but again Walter recalled that ‘the whole thing was very small, very private. There was no sort of proselytising.’ No more than ten people was the norm. Teachers and group leaders never took money for running the groups, though expenses were covered by donations, as can be seen in pages from Walter’s logbook of the time (1962-3). Norman Martin also remembers some of the practical procedures. A group would start by talking about the tree and its correspondences. Then members would be put into grades corresponding to the Sephiroth, and people would progress from one to the next. Generally speaking the progression wasn’t by ritual but by simple acknowledgement. However, sometimes there were more ritualistic, even dramatic occasions set up to propel the seeker across the threshold. Norman’s own initiation into the group was made rather mysterious. He was told that he had to meet ‘the Goat’ on the London Embankment in the middle of the night. The Goat turned out to be Alan Bain, by dint of his being a Capricorn, and together they walked and talked until Alan eventually declared that the moment of initiation had come. He raised his hand, and that moment, by synchronicity, (or perhaps by careful timing!), Big Ben chimed. Norman was in! Not everyone was happy about stepping higher up the tree – a tale is told about a young French lad who pleaded to be allowed to progress to Netzach, but when granted his wish burst into tears and asked to be taken back to Hod. Keeping a sense of humour was important, and there were all sorts of sayings bandied about, such as ‘Funny how it works!’ ‘You’re quite bright, you work it out!’ and ‘From the sublime to the gorblimey.’But although entertaining incidents are recounted with a chuckle, looking after the welfare of the group was also a priority, and in general, people weren’t pushed further than they wanted to go. There were two other main sources of study for group members. Getting a reader’s ticket to the British Museum Library was a must for some, including Glyn Davies and Alan Bain. The iconic, circular reading room in the British Museum (now replaced by the separate British Library) was a magical place in its own right. You had to apply with a reference from a serious scholar – being a registered student or just an interested member of the public wasn’t enough. Alan Bain managed to get his reference from Geoffrey Watkins, son of the founder of Watkins Bookshop. (a very good history of Watkins, which played such a part in the education of many Kabbalists, is given here). In Alan’s memoir, (see here) there is an excellent account of what it was like to penetrate the holy of holies, and to summon up books from the hidden depths of the library. As Alan affirms, this was a place to find real classics of esoteric literature, including works by past masters such as John Dee and Robert Fludd. However, the aim was not so much to lose yourself in old magical tomes but to ‘get yourself an education’, not perhaps in the conventional sense, but to develop a sense of how the river of knowledge had flowed down through the centuries. The training helped people to look beneath the trappings to the message or understanding conveyed in earlier writings. The other input came directly from the School of Economic Science and the Study Society. Glyn Davies and a few others were members of these organisations as well as ‘the Group’, and through Glyn’s connections, SES agreed to offer a programme of study which could be followed in the group. SES training emphasised intellectual and philosophical approaches, and introducing this material into the group was probably aimed at strengthening these abilities. It would round out the training, so that members could operate in a more detached way if necessary, and not rely solely on intuition and psychic experiences. Although SES gave this permission, rumour had it that they had also planted ‘a spy’ in the group in the form of Richard Henwood! Richard, although liked by everyone who knew him, eventually found the pressure of this combined approach too much and had to leave, although he remained affectionately in touch with various group members until the end of his life.

Note: Richard Henwood wrote an unpublished novel based largely upon his experiences in the Group. Despite searching, and despite several contacts having seen this novel, we cannot find a copy, but would very much like to see it if anyone can supply this. Eventually, the Soho days came to an end. Eventually too the ‘Group’ was replaced by other developments – Alan Bain left London, and later took his work into the arena of the Independent Catholic Church and the Theosophical Society. Tony Potter began his own line of teaching in North London, under the name of ‘The Society of the Hidden Life’, with particular emphasis on the ‘stop exercise’, which he developed as a key practice. Walter Lassally became too busy with his work as a travelling cinematographer to run groups regularly, although he continued to work with Cabala and the I-Ching to the end of his life; Robin Amis developed his own type of teaching known as ‘The Society of the Inner Life’ in the context of the Orthodox Church, and Glyn Davies convened astrology and Kabbalah groups from the late 60s onwards, which eventually evolved into Saros. It’s easy to forget, given the seriousness of purpose, and the long-lasting effects of the Group, just how young these leaders were in the Soho days. Most were still in their twenties, and so as careers developed, families grew, and life challenges faced them, some took other routes. However, all those to whom we’ve spoken have deeply-embedded memories of the era of ‘the Group’, and a strong sense of what it meant to them. With thanks to our principal informants on the workings of ‘the Group’: Keith Barnes, Lionel Bowen, Norman Martin, and to Walter Lassally and Robin Amis in memoriam. Cherry Gilchrist

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsArticles are mostly written by Cherry and Rod, with some guest posts. See the bottom of the About page for more. A guide to all previously-posted blogs and their topics on Soho Tree can be found here:

Blog Contents |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed