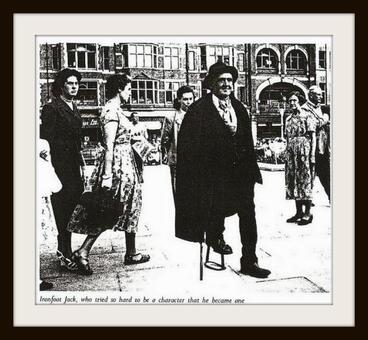

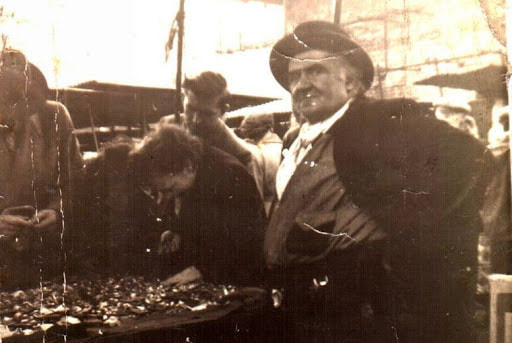

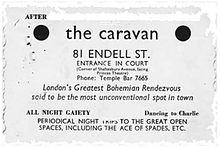

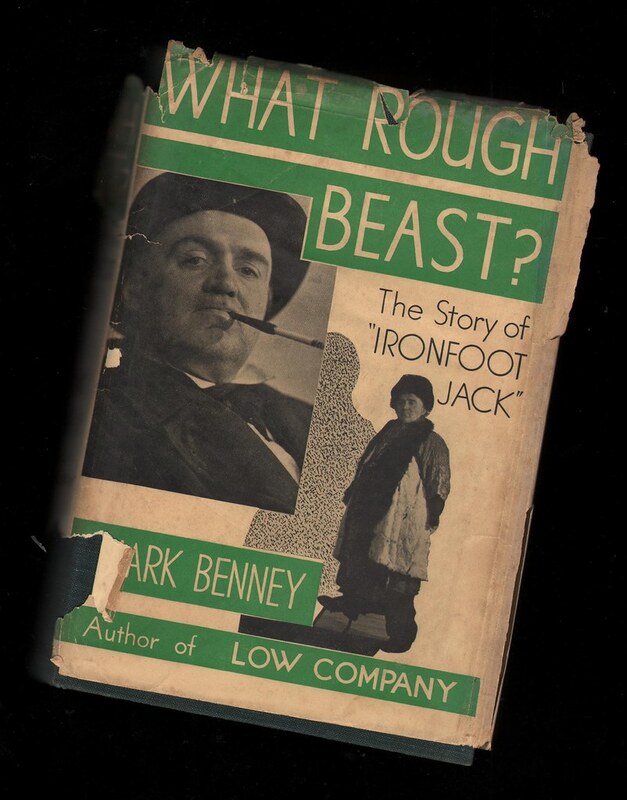

Ironfoot Jack –The Trickster of Soho ‘A Man Who Knows How To Get By is what they call seventy-year-old Ironfoot Jack Neave in the clubs and cafes of London's Soho. For years I have seen him limping around, brief-case under his arm, leaning heavily on a stick—a tired-looking old man in a velvet jacket. Never have I detected any evidence of prosperity in his appearance. Yet he is pointed out as a man who has successfully lived on his wits for fifty years.’ So said a journalist in The People newspaper, 1952. But, as he also reports, Ironfoot Jack’s own assumed title was that of ‘The King of the Bohemians’. What are we to make of this mixture of grandeur and poverty? During the time the Group members were roaming Soho, Jack was also prowling around the area. He was a well-known figure on the scene, and proud of his Bohemian status, even if he was succumbing to age and infirmity. He wasn’t a member or associate of the group; he had leanings towards the Occult, but more in the manner of a fairground fortune-teller, using a little knowledge and a lot of talk to make a quick shilling or two. (It’s doubtful, though, whether he had the psychic ability of many such traditional fortune-tellers.) To be fair, he loved books in a haphazard and self-taught manner and – if his own account is to be believed –had a handle on basic numerology and astrology (he supplied ‘orrerscopes’), as well as dipping a grubby toe into the waters of philosophy, spirituality and cosmology. More of that later. Jack Neave was born in Australia in about 1881, but came to Britain with his mother as a child. The adventures he recounted of his life before arriving in Bohemian London were hugely exaggerated - his famous ‘ironfoot’ was needed, he says, after a shark bite, whereas general opinion was that the damage was caused by an accident with machinery. Apparently, when he got drunk, the metal dragged along the road and struck sparks. [1] How are we to define Ironfoot Jack? To some he was a joke, to others a petty crook or a charlatan, but I suggest he was a significant figure in the ‘super-tramp’ line. And, as I’ll attempt to show, he was a reflection, albeit a distorted one, of the esoteric life of the time. Overall, he was a wanderer in the same vein as the Welsh poet W. H. Davies, who wrote The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp in 1908, which kicked off excitement among the liberal literati of the day. Being a tramp became fashionable for a while. Jack could speak ‘polari’, the showman’s language [2], liked to consort with gypsies, and had much of the mountebank, the card-sharper, the junk dealer and (with a capital letter) the Trickster in his make-up. He roamed, camped, begged, scavenged, and traded all over the UK, but was most at home in London, where he could blend happily both into Bohemia and the ranks of itinerant street traders.  What we know about Ironfoot Jack has recently been greatly enlarged by the publication of his memoir, The Surrender of Silence. This manuscript was found among Colin Wilson’s papers by Colin Stanley, his bibliographer, and had been transcribed from a recording. Jack had dictated his recollections and had them typed up in the hope that his famous author friend Colin would find a way to publish it. Long after his death, this has now come to pass. How does the life of Ironfoot Jack relate to the Soho Group? He was a familiar figure to them, but not a member, and probably not someone who even sat in on the café discussions – Jack thought he knew everything already! But Jack’s manner of life chimed in – sometimes in curious ways – with what the group members themselves did, and the philosophy they lived by at the time. Getting by For a start, there’s the way in which Jack ‘got by’ – as per the appellation in The People newspaper. He learnt to live like a king (again, as he called himself) on very little, on the scraps which no one else valued. He would go to Covent Garden, where ‘if you found vegetables in the gutter…they were yours’ And for fourpence, a butcher would sell you ‘little bits of odd meat’ known as ‘block ornaments’. He relates that: ‘All these little secrets it was necessary to know, and with this you could make a stew to keep four people – as much as they could eat – for two days.’[3] (He has a few more tips to offer, involving stale cakes and fish heads!) This resonated with the way that some of the group members chose to live. They often took casual jobs, scraping together just enough money to rent a bedsit or small flat, and to provide just enough food for everyday sustenance. This then gave them a kind of freedom, awarding them time and flexibility, and releasing them from consumer pressures. When Keith Barnes and Glyn Davies lived together, for instance, they too would go first to Covent Garden to glean vegetables, then on to Smithfield to scrounge a bone ‘for the dog’. According to Keith, Glyn always had a pot on the go, into which he would throw the bone and the veg. ‘Very tasty!’ The Group philosophy was also about stripping away old habits, and discovering how to earn and take only what was necessary. This wasn’t a principle of austerity, but of learning to rely on providence while still making an active effort; the old saying, ‘God will provide, but first lay your own knife and fork’ was bandied about. Glyn once told me how he decided to live entirely from ‘necessity’ for a while. He ate and slept according to what came his way; one night, peering into a waste bin on the street, he saw a beautiful newly-baked loaf of rye bread lying there, delivered just in time for his evening supper after he had resigned himself to going hungry. This way of life also resonates with the principles of alchemy, which are about taking ‘what others have rejected’ as the base material which can be transformed into precious gold. Fiddling for a living Then there were Jack’s ways of making a living from selling this and that, known in his day as ‘fiddling’, but without the connotations of trickery as in modern usage. Take, for instance, his method of buying up lots of ‘clutter’ very cheaply, usually old jewellery and coins which he would turn out onto his sales board as if they were a pile of old rubbish. Indeed they were for the most part, but Jack added his own special twist. He would gild a few of the coins beforehand so that they gleamed like gold. Then the customers thought him an old fool who didn’t know the value of what he had, and were quick to snap up handfuls of his offerings for sixpence or a shilling. Jack, however, knew exactly what he was doing, and profited handsomely. No one was robbed, but he took advantage of people’s natural greed. Does this perhaps remind us of the philosopher-sage Gurdjieff’s trick of dying sparrows yellow and selling them as ‘American canaries’? This he recounts in his semi-autobiographical book Meetings with Remarkable Men [4], adding that he was able to sell more than eighty of these exotic birds to the canary-loving natives of the city of Samarkand. Gurdjieff’s teachings formed a background to the Kabbalistic studies of the Group, some of which filtered in via the study material supplied by the School of Economic Science. (see the blog post ‘The Soho Group – how did it work? 18th Feb 2020) The 'School of Wisdom' A third aspect of Ironfoot Jack’s activities is the way he could conjure up a scene to stimulate people’s interest, and engage them. Some of this was not out of keeping with basic magical ritual techniques – also studied in the Group - where using ‘props’, and sound, scent, and colour, can help to evoke a special atmosphere, which in turn can lead to a state of heightened awareness. Ironfoot Jack was mainly out for his own amusement and enrichment however, and it’s important to emphasise that the Soho group and its descendants aimed never to take advantage of people in an unethical way. Nothing better illustrates Jack’s prowess in this respect than his description of setting up his own teaching school, in the pre-war period. First, he was offered premises on New Oxford Street at fifteen shillings a week: ‘I soon collected a few of the poor artists and between us we put some fantastic murals on the wall, and got some orange boxes and covered them with lino and then made cushions out of rags, drew some weird pentagrams and designs on the wall, and put the Twelve Signs of the Zodiac on the ceiling. Then I contacted friends who had a little bit of influence and drew up a pamphlet. And this is what the pamphlet said: ‘A Leaflet Announcing The Opening Of A School Of Wisdom’. It worked. And, to do Ironfoot Jack justice, it thrived on lectures and discussions. ‘There were even lectures that you couldn’t hear in Hyde Park; you certainly couldn’t hear the peculiar theories that were discussed at any political meeting.’[5] ‘Peculiar’ is probably right… Is this a kind of grotesque distorting mirror, held up to the more genuine lines of wisdom teaching on offer then and now? Or were Ironfoot Jack’s enterprises more at the Trickster end of the spectrum? Perhaps, though, in the end Jack was tricking himself more than anyone else as he did seem to believe in the grandiose abilities that he claimed. However, it’s said that the Fool can hold up a mirror in which we can see truth, as well as folly. [6] One of Jack’s favourite activities was to don a robe, spout a few solemn quotes from the tomes he had read, and convince people that he was a Master. The illusion didn’t generally last long, and his carefree attitude seems to have been that if they were enjoying themselves and getting something from it, then why not? Although this attitude did land him in prison, after he set up a somewhat unsavoury nightclub known as ‘The Caravan’. The Bohemian Philosophy

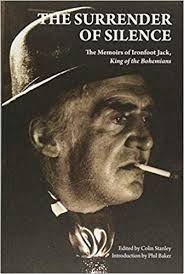

Finally, one external value of Ironfoot Jack’s memoir is the light that it sheds on the Bohemian element that was thriving in Soho before the war. Bohemianism was the prelude to the Soho Group, and even indeed to the 1960s ‘New Age’. Jack describes it thus: ‘The main basis of the Bohemian philosophy was that Creation came first, then the problem of existence, survival to live and avoid all misery as much as possible – to live to live.’ Life as also there to be shared with others and ‘harmony was the thing.’ Although this was Ironfoot Jack’s definition, in support of his lifestyle, it does clarify something of Bohemianism, its reliance on the moment and spontaneity, and it sets a tone for the later beatnik and hippy philosophies. Jack’s memoir also helps to chronicle some of the earlier esoteric and spiritual lines operating in London in the 1930s: ‘Many characters were studying Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, the Druids, the Rosicrucians, and there were many little Occult groups who were not practising the Occult in the orthodox way, but were researching into it, trying to find out all they could about it.’ This enables us to understand what bridged the gap between the 1950s stirrings of interest in Kabbalah, and the earlier era of the Golden Dawn, spiritualism, and the prominence of the Theosophical Society. So, Ironfoot Jack may have provoked a chuckle or two among the Soho group members, but he somehow echoed, albeit in a crude and distorted way, the more serious aspirations of the group itself. If you read his memoir, it’s easy to chuckle too, and to end up with a certain fondness for the old rogue. Notes [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iron_Foot_Jack [2]Polari is a form of cant slang used in Britain by some actors, circus and fairground showmen, professional wrestlers, merchant navy sailors, criminals, prostitutes, and the gay subculture. There is some debate about its origins but it can be traced back to at least the 19th century and possibly as far as the 16th century. There is a long-standing connection with Punch and Judy street puppet performers, who traditionally used Polari to converse. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polari [3] The Surrender of Silence p.87 [4] Described by Gurdjieff in his semi-autobiographical book, Meetings with Remarkable Men [5] The Surrender of Silence p.61 [6] See Cherry Gilchrist, Tarot Triumphs, (Weiser Books, 2016) Chapter Five Cherry Gilchrist

3 Comments

Colin Stanley

17/11/2020 02:14:03 pm

Ironfoot's manuscript of 'The Surrender of Silence' and his photographs etc (some of which are featured in the book) are in the Colin Wilson archive at the University of Nottingham

Reply

Peter Barnett

12/6/2024 05:39:06 pm

I brought the book and it was a great read. About Soho and a London that was around just before I was born. All but vanquished now.

Reply

13/6/2024 02:18:00 pm

Many thanks for your comments Peter. It is always nice to get positive feedback about projects that you have spent a lot of time working on. Cheers!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsArticles are mostly written by Cherry and Rod, with some guest posts. See the bottom of the About page for more. A guide to all previously-posted blogs and their topics on Soho Tree can be found here:

Blog Contents |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed