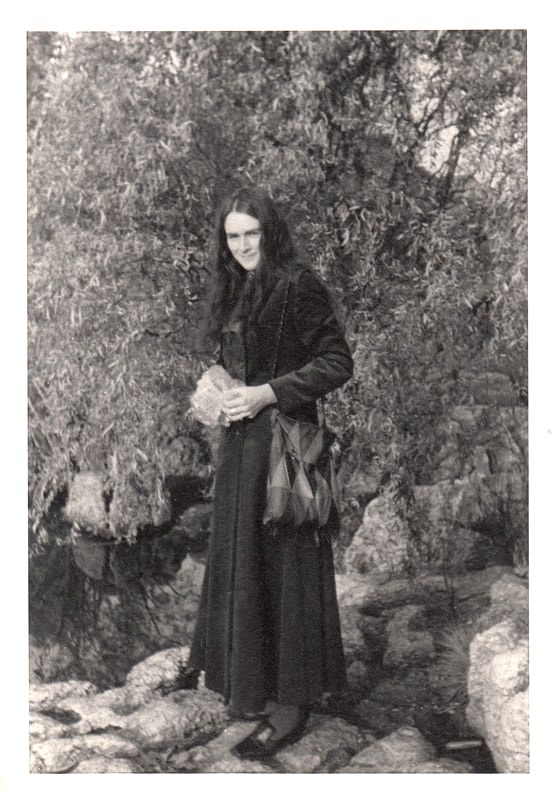

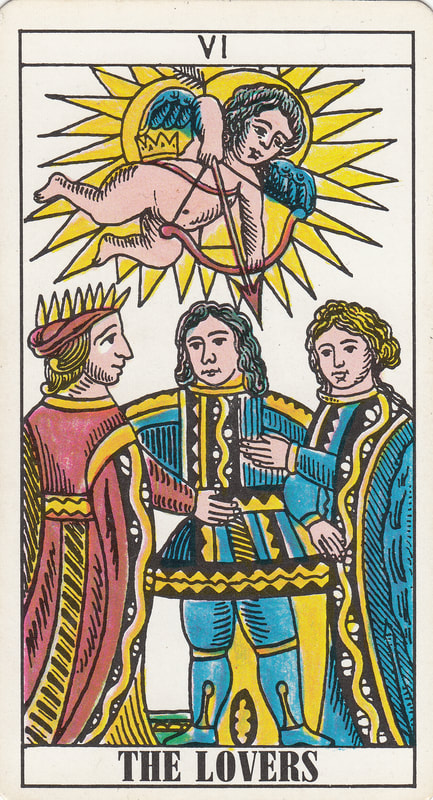

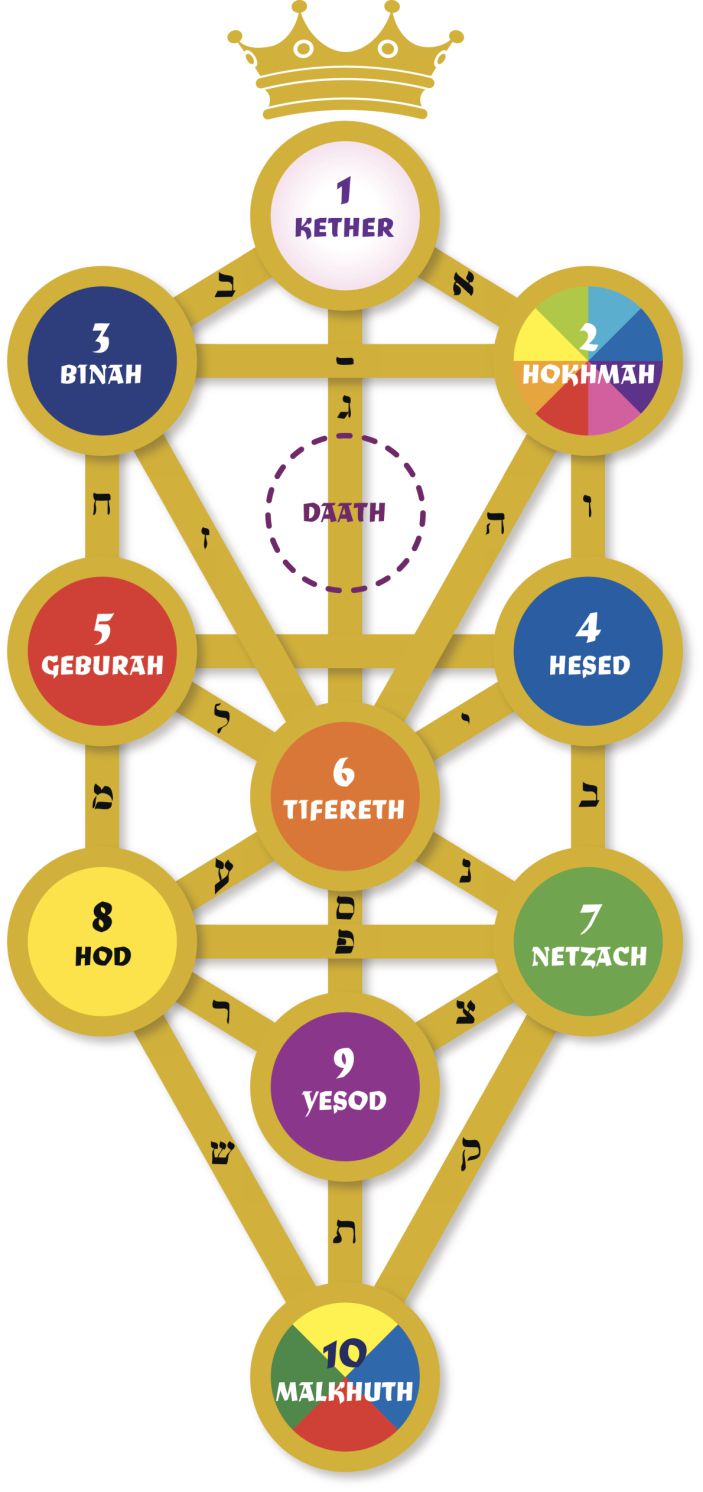

Part One of a Memoir by Cherry GilchristThis website takes as its starting point the Soho groups of the 1950s, and traces lines of descent which have emerged from these early Kabbalah groups. I discovered Kabbalah at the start of the 1970s, and this too was an influential period. There is never perhaps any definite starting point for where a line originated – back to Adam and Eve, in fact, as tradition has it! – but there are clearly times which are watershed moments. The development of the Soho line and its evolution into different teaching schools was certainly activated by the open culture of the late 60s and early 70s. For me, this is where the story becomes one of experience as opposed to research and stories told from bygone times. So in this account, I’ll relate something of that experience: in the first part, of how Kabbalah came into my life and the context which surrounded it, plus early development of new groups and organisations. In the second part, I’ll focus on what that first working group was like, which I joined. A Talk on the Tarot In February 1970, as a final year student at Cambridge, I found a typed slip in my college pigeon hole advertising a forthcoming talk on Tarot and the Tree of Life, organised by the Society of the Common Life. It pricked my interest, as I’d made a connection with Tarot a year or so earlier. I persuaded Chris, (my then boyfriend), that we really should go. On the night in question, we made our way to the designated room in one of the colleges, which was set out with rows of chairs and a slide projector and screen. So there were to be pictures! That augured well. A fair number of people were already waiting; We took seats on the left-hand side of the aisle. As the start time grew near, an expectant hush fell. And then I looked round to see a man walking purposefully past me to take his position as speaker, looking neither to left or right. I experienced a curious jolt of awareness, and the immediate thought, ‘What a strange looking man!’ He was in his 40s, short and rotund, with long hair neither of the current hippy style nor typical of his own generation. I could not place him. He looked very together in one way, but more than a touch dishevelled. Not arty, not wealthy, but not down and out either. He certainly didn’t fit neatly into a category. And when he spoke, it had an immediacy, including all of us in a way that I wasn’t used to after attending three years of lectures as a student. This was Glyn Davies, a Welshman, and one of the three leaders of the original Soho Kabbalah Group. I had no notion of it then, but he was to become my mentor for nearly forty years (he refused to take the name of teacher). The talk itself intrigued me, and the magnified images of the Tarot cards on the screen suffused my imagination afterwards, although as yet I knew very little about the Tree of Life, the diagram on which he placed them. But I wanted to know more about this cosmic map, which joined our small lives to a bigger world. I was also haunted by a frightening dream which I experienced in the aftermath of the meeting. Fear had been a part of my life for a while now, and a heightened sense of the fragility of life. I sensed that I had to shift my base of awareness, however difficult that might be – there simply wasn’t a choice. I had started a meditation practice some months ago, which had been a good start, but now the Tree seemed to draw me in. Or did I remember it from other times, other lives? At any rate, I felt compelled to write to Glyn about the dream, going to some trouble to track down his address. I received a reply, which I learnt later was a rarity, as Glyn was one for direct talking, rather than letter writing. He admitted later that his curiosity was piqued as he prided himself on remembering everyone from the meeting, but simply couldn’t place me, even though I’d asked a question there! It wasn’t long before we were in regular contact with him, either when he came back to Cambridge for further meetings, or, as time went on, in his kitchen in the battered old Maida Vale flat where he lived with his wife Gila and their young daughter. ‘Glyn’s kitchen’ in fact became legendary as a meeting point for all the many friends and seekers who sought him out over the years. (See Tessellations by Lucy Oliver.) The mix of possibilities The first early Soho groups were held from the late 1950s onwards, but by the time of my initial contact with Kabbalah, they had more or less split into separate teaching lines, the main ones of which were led by Alan Bain, Tony Potter, Robin Amis and Glyn Davies. (see here). My encounter with Glyn and attendance at meetings runs roughly in parallel to the memoirs contributed to this website by Rita Tremain and John Pearce, who worked primarily with Tony Potter. It was overall a time of great possibilities, and a much wider network of connections than had existed in the original times of the Soho Kabbalah groups. The microcosm of the coffee houses, with their floating clientele and aura of ‘you never know who you might meet’ had given way to a broader stage, with teachers and lines of spiritual work emerging from all kinds of traditions. At the time of encountering the Tree, I was already practising meditation, having joined a Samatha Buddhist Meditation class the previous September. And curiously enough, it was Samatha which brought me to Kabbalah. Lance Cousins, who was a senior member of the Samatha meditation classes had also arranged the leaflet drop about the talk on Tarot. He was on close terms with both Glyn and the Samatha teacher Nai Boonman Poonyathiro. Although primarily a Buddhist himself, he appreciated the Tree of Life teaching, and in fact was the very first person to show me a diagram of the Tree. My sense of chronology fails me here, but I think it must have been just before the Tarot talk, and I had a curious sense of another dimension opening up, which stayed with me for several days. So this was also a powerful factor in drawing me to attend the talk. I mention Lance Cousins in particular because it was through him primarily that a close alliance was forged between the Kabbalah and Samatha groups, an alliance which has persisted to this day. At one point in the late 1970s, the two organisations (Samatha and the fledgling Saros) considered whether they might even run a centre together. In the early stages of this quest, a party of both set-ups visited a possible venue – a decrepit stately home in Bedfordshire. I remember it well, and with some horror! Its crumbling cellars, decades of debris, and a full repairing lease were enough to deter most of us from taking it on. Samatha and Saros subsequently evolved in their separate ways – Samatha founded what was become a permanent centre at Greenstreete, in the Welsh Borders, whereas Saros held the centre at Buxton for several years until it was ‘job done’. But the two networks still have close links and overlaps today. The Cambridge Meetings Following that first meeting in February 1970, I eagerly attended other meetings put on by the ‘SCL’ during my final few months at Cambridge. ‘Society of the Common Life’ had been used as a working name since the first Soho groups in the late 1950s, and had its origins in an earlier lay brother-and-sisterhood (see our post on Common Life). The ethos was that anyone could use it, but that no one could ‘own’ it. At Cambridge, the name thus served as a kind of umbrella for talks by invited speakers from various backgrounds, whose interests touched on ‘the perennial wisdom’. Pir Vilayat Khan, for instance, gave a talk on his Sufi tradition. Later, in the mid-70s, our Kabbalah group in turn organised similar talks, some public, such as one with the Indian Guru Sri Chinmoy, and more private sessions with teachers from other types of Kabbalistic traditions, such as Gareth Knight and James Sturzaker. The emphasis was on following our own developing line of work, but being open to hear what was of value from other traditions. Returning to the SCL meetings in the spring and summer of 1970, some were more for discussion about topics such as meditation, and for regulars rather than the wider public. Two key figures who took a hand in the organisation for these were Richard and Millicent Ellis, old friends of Glyn Davies; they were all in the School of Economic Science and the Study Society at the same time. (See our post about these organisations here.) The link with these schools was another time-honoured one, as the early Soho Kabbalah groups had a working agreement with SES to study their material. The Study Society was also where Warren Kenton met Glyn Davies, who sparked off Warren’s own interest in Kabbalah. (See Warren's autobiography, 'The Path of a Kabbalist') Cross-Connections Another connection between SCL and Study Society was a shared interest in the Gurdjieff work and that of his former pupil Ouspensky, including the sacred dances known as the Gurdjieff Movements. Likewise, it was also possible to learn the Sufi ‘turning’ dance at the Study Society, with authority granted by one of the Mevlevi sheiks from Konya. (This is still offered today - see here.) I was taken to the magnificent old dance studio at Collett House in London on one occasion by Millicent Ellis to watch the turning ceremony, conducted with great dignity and dedication. And this ‘turning’ did also play a part in Saros activities for many years, in something of a different form. We also had direct connections to both the Mevlevi and Helveti-Jerrahi order of Sufis in Turkey, although that is another story. The cross-flows have thus been complex over the years. SCL Kabbalah groups and later Saros groups did not teach the Movements or the Gurdjieff/Ouspensky philosophy directly, but members often studied these in other contexts, and the Gurdjieffian language and concepts frequently formed a part of our discourse. In the mid-70s, an assorted bunch of Buddhists, Kabbalists and Study Society, enthusiastically formed a group to read aloud the whole of Gurdjieff’s epic work, Beelzebub’s Tales to his Grandson. When weather permitted, we sat outside on frayed, unravelling Oriental rugs to read aloud chunks of the dense and often impenetrable material. Small feasts followed, including some lethal home-made wine, in the true Gurdjieffian tradition. After all, as Gurdjieff himself said, ‘When you go on a spree, go the whole hog, and don’t forget the postage!’ Divergence

As time went on, the connections became more circumscribed. The heady and joyful exchanges between different teachings were somewhat dampened by careful scrutiny. Stronger boundaries might be required, to protect sensitive work done in groups, and choices had to be made if it became apparent that certain types of practice did not combine well with others. Personal responsibility was key, and everyone was free to choose as they wished, but it wasn’t always possible to ride two horses. Some people left Kabbalah groups, for instance, to embrace Buddhist practices more fully, or (as in my case) chose to align both a meditation practice and study to the Kabbalistic tradition. This did not usually mean cutting off from former colleagues - thankfully, friendly relations between different set-ups were largely maintained. However, but there were occasional fractures, underhand manipulations, and even serious breaches of trust. The ‘open door’ policy had to be re-configured in a more cautious way. Perhaps this was inevitable. But that earlier openness made for a wonderful leavening period, as traditions encountered each other in open forum, and sincere seekers could be welcomed into groups of different approaches. The cauldron of possibilities had been stirred from on high. Even now, with the perspective of forty years or more, the complex network of interactions and collaborations is hard to clarify in its entirety. I have known nothing like it since, and suspect that such periods happen rarely, perhaps once in a hundred years or so. It’s been said that at times, ‘only a few people are needed to continue the work’. At others, many may respond to the opportunities and new waves of development are triggered. The philosophy may be ‘perennial’, but the forms it takes will change. Part of the work later undertaken by Saros – and prompted by Glyn Davies – was to look at reformulating the teaching not just today but for three hundred years’ time. A tall order! And puts us in mind of another expression in the teaching: ‘Work for yourself, work for others, work for the Work’s sake.’ We may join a teaching tradition to save our souls, but it gradually becomes clear that we need to offer service as well. In the next part – having focused on the cross-currents, and general development of ‘SCL’ groups in this section, I’ll be putting the spotlight on how a Kabbalah group in the early 1970s functioned, based on my experience from the time.

2 Comments

Pearse Coughlan

10/1/2022 02:08:07 pm

Fantastic to trace the early lines, individuals and thoughts. Thankyou and looking forward to future contributions to the work.

Reply

19/1/2024 09:15:12 pm

Just found this by accident - this was paet of my life too!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsArticles are mostly written by Cherry and Rod, with some guest posts. See the bottom of the About page for more. A guide to all previously-posted blogs and their topics on Soho Tree can be found here:

Blog Contents |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed