|

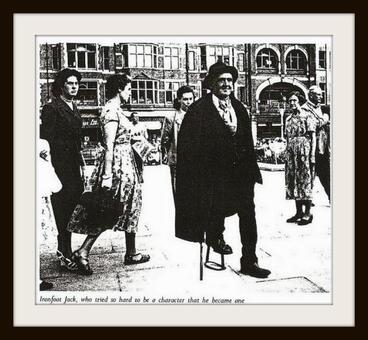

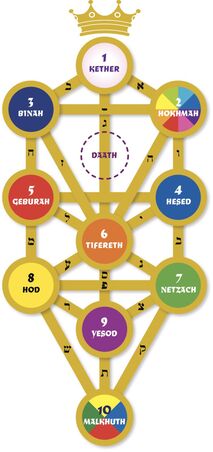

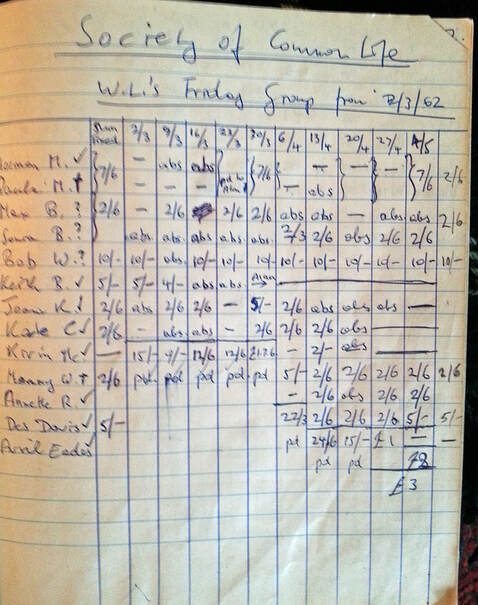

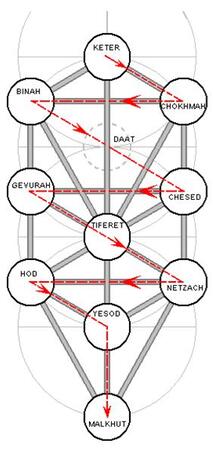

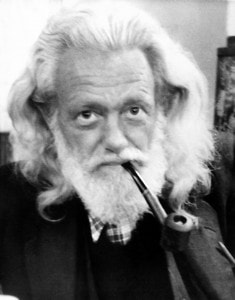

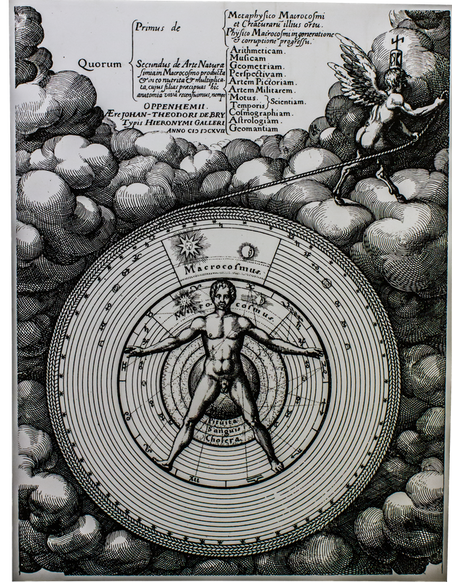

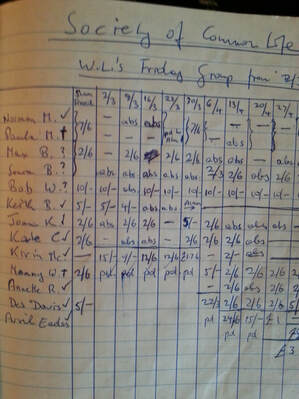

This blog gives an overview of Walter Lassally’s life, work, and his involvement with Kabbalah. You can read a fuller account at Cherry's Cache, which describes a meeting which Cherry Gilchrist and Rod Thorn had with Walter Lassally in 2014, where he shared his recollections about the early Soho Group, and gives details of his I Ching readings. Walter Lassally was one of the Soho Kabbalists, and a famous cinematographer, who won an Academy Award for his filming of Zorba the Greek in 1965. However, his priority was the search for inner truth. As he wrote in his later years, for a talk entitled ‘The Universe and the Individual: The Cosmos and the Microcosmos’: ‘My career as world-famous Director of Photography is well known and has been written about ad infinitum. On the other hand my other activities in the realm of philosophy and esotericism are not so well known but have in my estimation been even more important and significant to me than my main occupation.’ Walter’s early life Walter was born in Berlin in 1926, growing up there during Hitler’s ascent to power. His father worked as an animator of industrial films, and the family was cultured and comfortably-off. However, although they were Lutheran Protestants, they had Jewish roots in earlier generations, and were therefore classified as ‘non-Aryan’ under the Nazi regime. In 1938, Walter was excluded from school, and his father was put in a concentration camp. But before war broke out, Walter’s mother managed to obtain a visa for the UK, which enabled her husband to be released. The family arrived at Dover with virtually nothing. Walter spoke no English, but soon made up for that and beat most of his English classmates in the exams! In the UK, his father was first interned as an alien, but then freed after a tribunal hearing, allowing the family to settle in Richmond, Surrey. Walter left school at the age of sixteen, already convinced that he wanted to be a film cameraman. He began as a lowly clapper boy at Riverside Studios, but swiftly became renowned as a cinematographer, shooting such well-known films as A Taste of Honey, Heat and Dust, and Tom Jones, as well as Zorba the Greek. In his early years, he was also associated with the radical ‘Free Cinema’ movement led by Lindsay Anderson, which you can hear in the clip below. Walter’s Quest How did he come across ‘the Group’? What aroused his interest? The quotes and information included here are from our face-to-face meeting with him in January 2014. ‘It was probably triggered by an unhappy love affair that I had in the early 1950s. And that led to what I would call the search for the self. Which is still going on…First of all, I turned towards Yoga – I read Paul Brunton’s book, a classic book about Indian yoga, and then I became interested in Gurdjieff and Ouspensky.’ One day in 1956 when he was in Soho, perhaps on film business – it was a hub for the film industry at that time -Walter entered a café where an energetic discussion was taking place. This was a gathering of ‘the Group’, probably at ‘the “Nucleus” [which] was the centre of it all, the coffee bar in Monmouth Street. And someone was always in there holding forth.’ The encounter was an eye-opener for Walter, and what he discovered there became his lifeline. He described this type of Kabbalah as ‘such a wonderful system. It’s both simple and complicated. It covers all the areas…the Tree is a terribly dense, but a relatively simple diagram. It’s not hard to understand, although you can study, and study and study ...the Tree in all its aspects, the paths on it, its connections with astrology.’ A few years later, he started running his own group. During our visit, he brought down old notebooks to show us, inscribed with ‘Society of the Common Life 1962’, listing attendance of members and their subscriptions. Astrology and the I Ching

Walter was also a keen and proficient astrologer, but his chief passion was for the I Ching. He recorded his I Ching readings for over 40 years, and turned them into a book, Thirty Years with the I Ching, which can be accessed online. (Click on the I Ching tab at the top of the Home Page then scroll down past the first article.) These I Ching diaries, which include his own reflections on the readings, reveal much about his relationship with the Work, as well as with his teacher Alan Bain, and with Walter’s partner Kate, all of which posed challenges. He remained committed to ‘the Work’ throughout his life. As he said to us at our meeting: ‘You have an aim, which can broadly be described as self-knowledge. The saying ‘Know Thyself’ – inscribed over the temple of Apollo at Delphi – is very important. …And now I firmly adhere to the idea that that is the only point of being on earth as a human being. Everything else is peripheral.’ Walter died in 2017, in Crete where he had spent much of his time in later years. Cherry Gilchrist

0 Comments

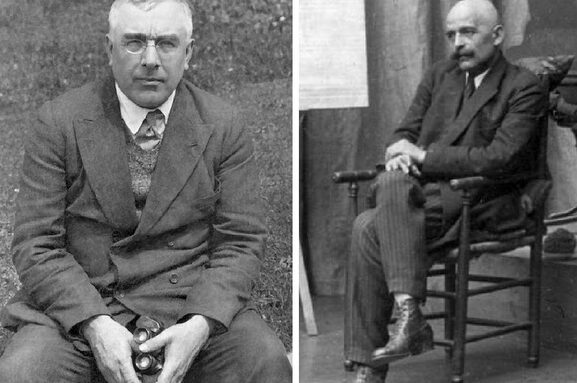

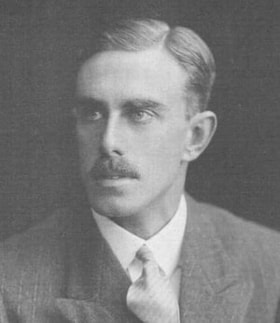

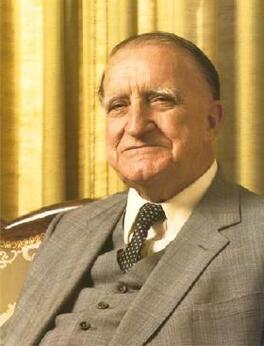

One theme that crops up in different branches of the Soho Tree is the idea that we are creatures of habit, acting automatically and unconsciously most of the time. The path of self-development involves waking up and stepping back from these mechanical processes. It’s likely that this theme came originally through the work of Gurdjieff. This article looks at the so-called Stop Exercise, as used within Gurdjieff’s tradition, and the way this and similar methods were used by Glyn Davies and Tony Potter. The enneagram, sometimes used as a symbol of the Gurdjieff Work, can be taken as showing the importance of shocks, also known as intervals, in automatic processes. Gurdjieff’s Stop Exercise Gurdjieff used the stop exercise as a way of developing awareness of habitual postures and movement. We hear about it first from Ouspensky, when he was with Gurdjieff in Essentuki in 1917: “In order to oppose this automatism and gradually to acquire control over postures and movements in different centers there is one special exercise. It consists in this – that at a word or sign, previously agreed upon, from the teacher, all the pupils who hear or see him have to arrest their movements at once, no matter what they are doing, and remain stock-still in the posture in which the signal has caught them. Moreover not only must they cease to move, but they must keep their eyes on the same spot at which they were looking at the moment of the signal, retain the smile on their faces, if there was one, keep the mouth open if a man was speaking, maintain the facial expression and the tension of all the muscles of the body exactly in the same position in which they were caught by the signal. […] Although the exercise concentrates on physical postures, Gurdjieff believed that our thinking and feeling followed these habitual physical postures. One can end up ‘stopped’ in the midst of a transition from one posture to another, in an unaccustomed position. This in turn leads involuntarily to thinking and feeling in a new way, to know oneself in a new way. In this way the old circle of automatism is broken. P D Ouspensky (left) taught the ideas and methods of G I Gurdjieff (right), from their first meeting in Russia in 1915, until Ouspensky’s death in England in 1947. Gurdjieff continued using the stop exercise in the Prieuré in the early 1920s, and again later. Thomas de Hartmann recalls several instances of the stop exercise, including a public demonstration: [2] “I would like to mention what took place during another demonstration, when at the very end Mr Gurdjieff shouted “stop.” Pupils on the stage held their postures, held them quite long. Then Mr Gurdjieff had the curtain brought down but did not say that the “stop” was finished. One of the pupils did not continue to hold the “stop” once the curtain came down and Mr Gurdjieff scolded her very strongly. He said that the “stop” had nothing to do with the audience or the curtain . . . that it is Work and cannot be finished until the Teacher says; that it has to be held even if a fire should break out in the theatre.” At some point in the 1940s, Gurdjieff produced a movement, one of the thirty-nine, in which the demonstrators unexpectedly, at their own discretion, call a stop. [3] I believe that this video shows a performance of this movement, with a stop taking place near the end: The Study Society and SES Ouspensky carried on with the stop exercise, and after his death it was practised in London within the Study Society. Francis Roles, the head of the Study Society was interested by the stop exercise and he wrote in 1962: [4] “An account by a traveller to Mecca in Blackwood’s Magazine, December, 1961, contains a description of a visit to a Sufi retreat, and such of the work there as this novice was allowed to see: One remarkable exercise was carried out by all members of the fraternity. Francis Roles (left) founded the Study Society after Ouspensky’s death, in order to carry on his work in London. He later worked with Leon MacLaren (right) to bring Ouspensky’s teachings into the School of Economic Science (SES). Connections with the Soho Cabbalists Glyn Davies and other members of the Soho Cabbala group were also members of the School of Economic Science (SES) and the Study Society in the 1950s and 60s (See The Soho Group - How did it work?). At one point, the entire group was invited to follow a programme of SES study, and when the Maharishi introduced Transcendental Meditation to London in the early 1960s with the help of the SES and The Study Society, Soho Cabbalists were also there. Cherry Gilchrist recalls a more recent experience of stopping during an event organised by SES: “For several years in the late 1990s, I took part in the Art in Action exhibition, hosted by the School of Economic Science, where I had been invited to help run the Russian Arts tent. During the set-up days before the public was admitted, I noticed that on the hour, every hour, a bell would be rung, and everyone would immediately stop what they were doing and keep total stillness for a minute or two. The effect was noticeable, and gave back a sense of calm and poise to what was, very often, a scene of frenzied activity.” The Inner Stop Francis Roles also mentions an “Inner Stop” exercise that was encouraged within the Study Society, which people can carry out themselves whenever they remember it [5]. The Inner Stop is discussed in more detail by Maurice Nicholl [6]: “Now, apart from the exercise where the body is made motionless, which can be called Outer Stop, there is another exercise similar but different, where the mind is made motionless. This is called Inner Stop. Both have to do with bringing about a state of motionlessness. But the two exercises are not performed in the same sphere. In the case of the first, the body in space is stopped. People may pass you, speak to you, tell you how silly you look, and so on. But your body and your eyes remain motionless in space. In the case of the second, the practice of Inner Stop, you stand motionless in your mind. Thoughts pass you, speak to you, ask you what you are up to and so on, but you pay no attention to them. You will see at once that Inner Stop is connected with a form of Self-Remembering.” Nicholl explains that the Inner Stop exercise is not the same as trying to stop your thoughts, but is more like remaining internally ‘motionless’ so that habitual thoughts and modes of reaction pass you by. Tony Potter (portrait by John Pearce) and the Cabbalistic Tree of Life. Tony Potter’s Stop Exercise A type of inner stop exercise was at the centre of Tony Potter’s “Society of the Hidden Life” approach to self-development. He used it as a tool for self-observation in relation to principles taken from the Cabbalistic tree of life – Reflex (Malkuth), Instinct (Yesod), Thinking (Hod) and Feeling (Netzach). In an article he wrote in later years he describes working with the first principle of reflex. [7]. He talks about how we can notice other people responding to changes purely reflexively: “Simply look around on a bus or a train and notice the number of people who are fidgeting, scratching, making unnecessary movements and generally behaving in a way which can only lead one to suppose that they are not in any way aware of what they are doing.” He goes on to explain that it is much harder to spot this kind of activity in ourselves, and that to do so we need to STOP at every available opportunity: “By this is not meant a frantic screeching to a halt, but a gentle, controlled flow to a standstill. This is obviously easier to achieve, at first, when the body is relaxed. The mind can then be allowed to empty. Unfortunately, it is in these circumstances that the least advantage is gained. The greatest effect is achieved when one STOPs in the midst of an otherwise turbulent situation. This STOP only needs to be momentary. If it is done correctly, the depth of the effect is quite unexpected and, the first time it is experienced, somewhat startling. Indeed, it has been written:- If, in the midst of troubled time, we stand aside, This may sound a little melodramatic, but it is in fact, an explicit description of a properly executed STOP. It has the effect of removing one completely from the limitations of time and space and enabling one to observe the environment as a completely objective phenomenon.” The painter John Pearce writes about his experiences of the stop exercise with Tony Potter [8]: “As taught in Tony Potter’s group, the Stop was a technique of instant meditation and self-observation to be practiced in any and every situation. Unlike other meditation techniques, it did not involve time-consuming detachment or special poses. Nor did it mean suddenly freezing physically. It was a way of stilling the mind, becoming inwardly aware of the body, breath and heartbeat as well as surroundings. Outwardly unobservable, inwardly time was suspended.” The meditation room at the Saros Centre, Buxton (1980s) The Stop Exercise in Saros The stop exercise was used from time to time on Saros courses, both during movement exercise and during regular work (I remember a lot of painting and sanding woodwork on courses!). The exercise was used as one of a number of techniques to disrupt habitual activity. Other methods would be to work faster than usual, or slower than usual. Ouspensky implies that Gurdjieff was very strict about stopping without any thought of harm – telling for example how a student burnt his hand during a stop. I don’t think there was quite that level of strictness in Saros, but I do recall something else that Ouspensky mentions – how people try to avoid the stop. In my case I can definitely remember once moving very carefully when I thought a stop might come, so that I would avoid being ‘caught out’! Rod Thorn Notes:

[1] In Search of the Miraculous, (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich 1977 Edition), p.353 [2] Our Life with Mr Gurdjieff, by Thomas de Hartman, (Penguin, 1972), p.111. There are other references to the stop exercise, on pages 35 (‘stopping’ in a tangled group) and 113 (‘stopping’ whilst on a ship en-route to New York). [3] Gurdjieff: Mysticism, Contemplation, and Exercises, by Joseph Azize (Oxford University Press, 2019) p. 102. Available on Google books at https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=-NjBDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA102 [4] https://www.ouspenskytoday.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/1962_10.pdf [5] https://www.ouspenskytoday.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/1979_27.pdf [6] Psychological Commentaries on the Teaching of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, by Maurice Nicoll. Volume 5, p. 1517. http://www.gianfrancobertagni.it/materiali/gurdjieff/nicoll_commentari5.pdf [7] Exercise of the Month in the first issue of the Pentacle Journal, published in June 1985, edited by Tony Potter. https://esoterichistory.wordpress.com/2016/10/06/stop-exercise/ [8] John Pearce: Art and Reality https://johnnpearceartist.com/art-and-realityart-and-reality/ Ernest Page ca 1960 from http://adocentyn.net/poetry-of-ernest-page/ Ernest Page was a fascinating Soho character, well-known to members of the group in the late 1950s and 60s. He was famous as the astrologer who gave readings for two and sixpence in Soho cafés. He lived rough and was always ready to help the homeless and vulnerable. People of all kinds would crowd around his café table for the sake of the talk. Writers, artists, philosophers were drawn into it, together with Soho’s habitue’s of all kinds, men, women, the old, the young, the ambitious, the derelict. Ernest was also a published poet, and perhaps most surprisingly (and unknown to most) he was also the warden of a secret magical order. In this work he was a force for reconciliation and his wide and genial sympathies encouraged membership from many different traditions. Dropping Out Ernest’s obsession with astrology began in 1956, when he suddenly decided to ‘drop out’, giving up his job with the Post Office and his accommodation in Highgate Hill; he felt that living between four walls had become too much of a burden. Ernest had been brought up in a well-to-do family in North London, and in his teens he was a lay preacher. In mid-life he converted to the Catholic Church, but then in that fateful year 1956 he suddenly walked out of church during Mass. He never abandoned his faith though, and his brother Ralph, a Catholic Priest, said of him ‘I preach the gospel – but Ernest practises it.’ Ernest (centre) with members of the Soho Group (a meeting staged for a film). Memories of Ernest Ernest was a close friend of the husband-and-wife team of Vivian Godfrey and Leon Barcynski, who wrote a series of books about the magical order they all worked in: “In Soho the fragile figure with the snow-white hair and beard was well-known, going through the narrow streets carrying a large leather bag in each hand (the one filled with astrological books and papers, the other with personal possessions) or presiding through the night at a quiet table in the corner of a crowded coffee-bar, drawing meticulous horoscopes and annotating them in his fine archaic script, checking the accuracy of his work by making quiet and often astounding observations on his client’s past life, sometimes spending an hour or more sifting the evidence for a particular time of birth: and all for a most nominal fee, or for no fee at all if he so decided: this work, like everything else, he did for the love of it.” The Magical Philosophy, Book I (Llewellyn, 1974) p. 165. Alan Bain, one of the founders of the Soho Group, writes about learning astrology from Ernest: “Ernest had worked for the Post Office for many years, until he discovered astrology, whereupon, overnight (as it seemed to him) he left his job to devote himself full-time to its study. And that is exactly what he did, even to the extent of finding himself homeless and often penniless. About astrology though he would hold forth enthusiastically for hours to anyone he thought was serious about sharing his study. I was, and he held forth! A better mentor I could not have found. Alan Bain on Ernest Page (read more here). Norman Martin, a member of the Soho Group, remembers Ernest as a friend: “Ernest wore a very clean raincoat, although he slept rough outside or in the British Museum reading room (his hair covering his face so they couldn’t see he was sleeping). Ernest was a Virgo, so quite finicky about appearance.” Norman gave Ernest a test – naming a month in the past and challenging Ernest to tell him what, if anything, had happened then. Ernest managed to deduce that Norman had travelled to Paris, which was true! He then explained how he had worked this out from the chart. The Poet Ernest was a keen poet, and some of his poems were published in a book entitled 14 Poems in 1949. He was also the subject of a poem, written by Arthur Jacobs, entitled The Astrologer: His flat and battered notebook Is like grey parchment with symbols Scrawled in its dust out of Babylon. He will set, for three and sixpence, Round your magic hour of birth The stars that in their movements Tell him the secrets your appearance Chose for itself. He is no crank, But a true survival from an ancient Art that promises trends, not detailed Incident. Consult him at your peril: For whether or not his assured vision Excites the protest of your intellect, Past and future turn before his gaze, Mortality lies naked beneath his fingertips. A. C. Jacobs Collected Poems & Selected Translations (Menard Press: 1996)

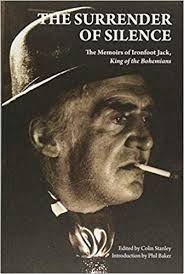

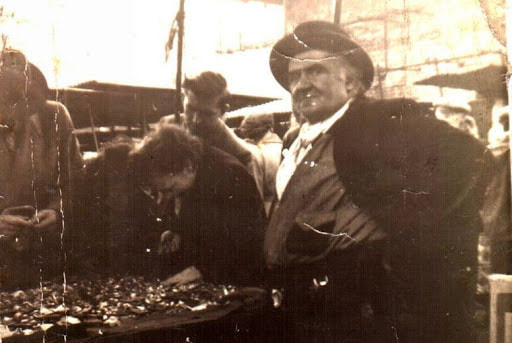

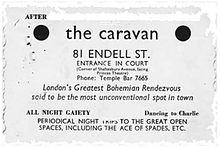

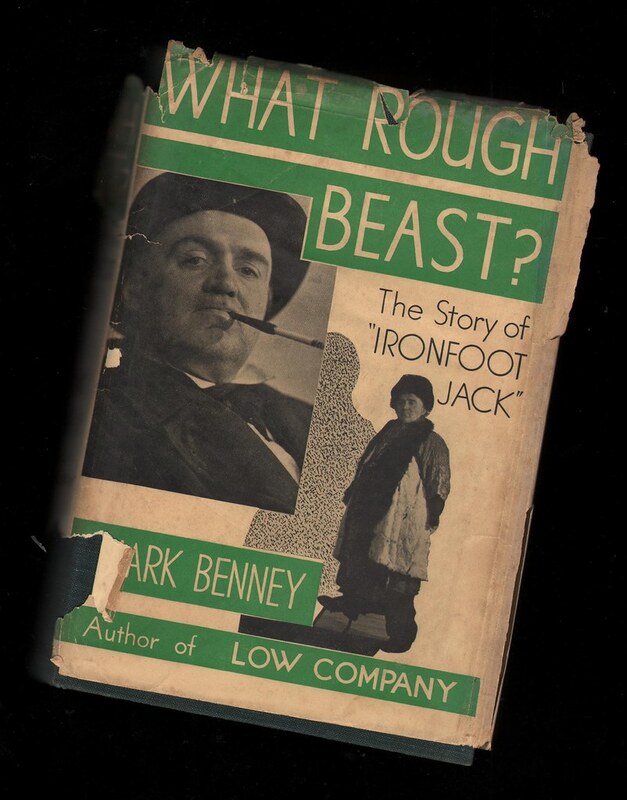

Ironfoot Jack –The Trickster of Soho ‘A Man Who Knows How To Get By is what they call seventy-year-old Ironfoot Jack Neave in the clubs and cafes of London's Soho. For years I have seen him limping around, brief-case under his arm, leaning heavily on a stick—a tired-looking old man in a velvet jacket. Never have I detected any evidence of prosperity in his appearance. Yet he is pointed out as a man who has successfully lived on his wits for fifty years.’ So said a journalist in The People newspaper, 1952. But, as he also reports, Ironfoot Jack’s own assumed title was that of ‘The King of the Bohemians’. What are we to make of this mixture of grandeur and poverty? During the time the Group members were roaming Soho, Jack was also prowling around the area. He was a well-known figure on the scene, and proud of his Bohemian status, even if he was succumbing to age and infirmity. He wasn’t a member or associate of the group; he had leanings towards the Occult, but more in the manner of a fairground fortune-teller, using a little knowledge and a lot of talk to make a quick shilling or two. (It’s doubtful, though, whether he had the psychic ability of many such traditional fortune-tellers.) To be fair, he loved books in a haphazard and self-taught manner and – if his own account is to be believed –had a handle on basic numerology and astrology (he supplied ‘orrerscopes’), as well as dipping a grubby toe into the waters of philosophy, spirituality and cosmology. More of that later. Jack Neave was born in Australia in about 1881, but came to Britain with his mother as a child. The adventures he recounted of his life before arriving in Bohemian London were hugely exaggerated - his famous ‘ironfoot’ was needed, he says, after a shark bite, whereas general opinion was that the damage was caused by an accident with machinery. Apparently, when he got drunk, the metal dragged along the road and struck sparks. [1] How are we to define Ironfoot Jack? To some he was a joke, to others a petty crook or a charlatan, but I suggest he was a significant figure in the ‘super-tramp’ line. And, as I’ll attempt to show, he was a reflection, albeit a distorted one, of the esoteric life of the time. Overall, he was a wanderer in the same vein as the Welsh poet W. H. Davies, who wrote The Autobiography of a Super-Tramp in 1908, which kicked off excitement among the liberal literati of the day. Being a tramp became fashionable for a while. Jack could speak ‘polari’, the showman’s language [2], liked to consort with gypsies, and had much of the mountebank, the card-sharper, the junk dealer and (with a capital letter) the Trickster in his make-up. He roamed, camped, begged, scavenged, and traded all over the UK, but was most at home in London, where he could blend happily both into Bohemia and the ranks of itinerant street traders.  What we know about Ironfoot Jack has recently been greatly enlarged by the publication of his memoir, The Surrender of Silence. This manuscript was found among Colin Wilson’s papers by Colin Stanley, his bibliographer, and had been transcribed from a recording. Jack had dictated his recollections and had them typed up in the hope that his famous author friend Colin would find a way to publish it. Long after his death, this has now come to pass. How does the life of Ironfoot Jack relate to the Soho Group? He was a familiar figure to them, but not a member, and probably not someone who even sat in on the café discussions – Jack thought he knew everything already! But Jack’s manner of life chimed in – sometimes in curious ways – with what the group members themselves did, and the philosophy they lived by at the time. Getting by For a start, there’s the way in which Jack ‘got by’ – as per the appellation in The People newspaper. He learnt to live like a king (again, as he called himself) on very little, on the scraps which no one else valued. He would go to Covent Garden, where ‘if you found vegetables in the gutter…they were yours’ And for fourpence, a butcher would sell you ‘little bits of odd meat’ known as ‘block ornaments’. He relates that: ‘All these little secrets it was necessary to know, and with this you could make a stew to keep four people – as much as they could eat – for two days.’[3] (He has a few more tips to offer, involving stale cakes and fish heads!) This resonated with the way that some of the group members chose to live. They often took casual jobs, scraping together just enough money to rent a bedsit or small flat, and to provide just enough food for everyday sustenance. This then gave them a kind of freedom, awarding them time and flexibility, and releasing them from consumer pressures. When Keith Barnes and Glyn Davies lived together, for instance, they too would go first to Covent Garden to glean vegetables, then on to Smithfield to scrounge a bone ‘for the dog’. According to Keith, Glyn always had a pot on the go, into which he would throw the bone and the veg. ‘Very tasty!’ The Group philosophy was also about stripping away old habits, and discovering how to earn and take only what was necessary. This wasn’t a principle of austerity, but of learning to rely on providence while still making an active effort; the old saying, ‘God will provide, but first lay your own knife and fork’ was bandied about. Glyn once told me how he decided to live entirely from ‘necessity’ for a while. He ate and slept according to what came his way; one night, peering into a waste bin on the street, he saw a beautiful newly-baked loaf of rye bread lying there, delivered just in time for his evening supper after he had resigned himself to going hungry. This way of life also resonates with the principles of alchemy, which are about taking ‘what others have rejected’ as the base material which can be transformed into precious gold. Fiddling for a living Then there were Jack’s ways of making a living from selling this and that, known in his day as ‘fiddling’, but without the connotations of trickery as in modern usage. Take, for instance, his method of buying up lots of ‘clutter’ very cheaply, usually old jewellery and coins which he would turn out onto his sales board as if they were a pile of old rubbish. Indeed they were for the most part, but Jack added his own special twist. He would gild a few of the coins beforehand so that they gleamed like gold. Then the customers thought him an old fool who didn’t know the value of what he had, and were quick to snap up handfuls of his offerings for sixpence or a shilling. Jack, however, knew exactly what he was doing, and profited handsomely. No one was robbed, but he took advantage of people’s natural greed. Does this perhaps remind us of the philosopher-sage Gurdjieff’s trick of dying sparrows yellow and selling them as ‘American canaries’? This he recounts in his semi-autobiographical book Meetings with Remarkable Men [4], adding that he was able to sell more than eighty of these exotic birds to the canary-loving natives of the city of Samarkand. Gurdjieff’s teachings formed a background to the Kabbalistic studies of the Group, some of which filtered in via the study material supplied by the School of Economic Science. (see the blog post ‘The Soho Group – how did it work? 18th Feb 2020) The 'School of Wisdom' A third aspect of Ironfoot Jack’s activities is the way he could conjure up a scene to stimulate people’s interest, and engage them. Some of this was not out of keeping with basic magical ritual techniques – also studied in the Group - where using ‘props’, and sound, scent, and colour, can help to evoke a special atmosphere, which in turn can lead to a state of heightened awareness. Ironfoot Jack was mainly out for his own amusement and enrichment however, and it’s important to emphasise that the Soho group and its descendants aimed never to take advantage of people in an unethical way. Nothing better illustrates Jack’s prowess in this respect than his description of setting up his own teaching school, in the pre-war period. First, he was offered premises on New Oxford Street at fifteen shillings a week: ‘I soon collected a few of the poor artists and between us we put some fantastic murals on the wall, and got some orange boxes and covered them with lino and then made cushions out of rags, drew some weird pentagrams and designs on the wall, and put the Twelve Signs of the Zodiac on the ceiling. Then I contacted friends who had a little bit of influence and drew up a pamphlet. And this is what the pamphlet said: ‘A Leaflet Announcing The Opening Of A School Of Wisdom’. It worked. And, to do Ironfoot Jack justice, it thrived on lectures and discussions. ‘There were even lectures that you couldn’t hear in Hyde Park; you certainly couldn’t hear the peculiar theories that were discussed at any political meeting.’[5] ‘Peculiar’ is probably right… Is this a kind of grotesque distorting mirror, held up to the more genuine lines of wisdom teaching on offer then and now? Or were Ironfoot Jack’s enterprises more at the Trickster end of the spectrum? Perhaps, though, in the end Jack was tricking himself more than anyone else as he did seem to believe in the grandiose abilities that he claimed. However, it’s said that the Fool can hold up a mirror in which we can see truth, as well as folly. [6] One of Jack’s favourite activities was to don a robe, spout a few solemn quotes from the tomes he had read, and convince people that he was a Master. The illusion didn’t generally last long, and his carefree attitude seems to have been that if they were enjoying themselves and getting something from it, then why not? Although this attitude did land him in prison, after he set up a somewhat unsavoury nightclub known as ‘The Caravan’. The Bohemian Philosophy

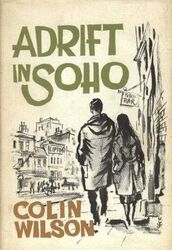

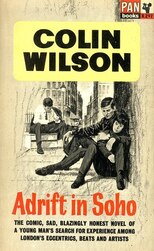

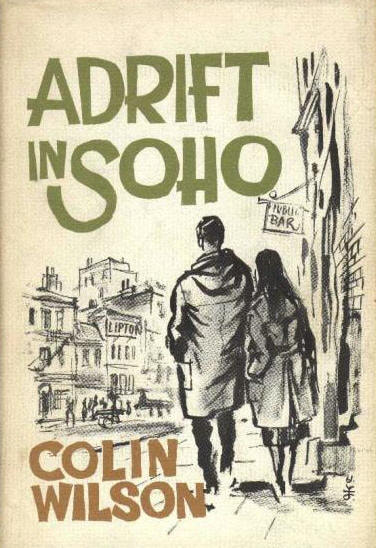

Finally, one external value of Ironfoot Jack’s memoir is the light that it sheds on the Bohemian element that was thriving in Soho before the war. Bohemianism was the prelude to the Soho Group, and even indeed to the 1960s ‘New Age’. Jack describes it thus: ‘The main basis of the Bohemian philosophy was that Creation came first, then the problem of existence, survival to live and avoid all misery as much as possible – to live to live.’ Life as also there to be shared with others and ‘harmony was the thing.’ Although this was Ironfoot Jack’s definition, in support of his lifestyle, it does clarify something of Bohemianism, its reliance on the moment and spontaneity, and it sets a tone for the later beatnik and hippy philosophies. Jack’s memoir also helps to chronicle some of the earlier esoteric and spiritual lines operating in London in the 1930s: ‘Many characters were studying Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, the Druids, the Rosicrucians, and there were many little Occult groups who were not practising the Occult in the orthodox way, but were researching into it, trying to find out all they could about it.’ This enables us to understand what bridged the gap between the 1950s stirrings of interest in Kabbalah, and the earlier era of the Golden Dawn, spiritualism, and the prominence of the Theosophical Society. So, Ironfoot Jack may have provoked a chuckle or two among the Soho group members, but he somehow echoed, albeit in a crude and distorted way, the more serious aspirations of the group itself. If you read his memoir, it’s easy to chuckle too, and to end up with a certain fondness for the old rogue. Notes [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iron_Foot_Jack [2]Polari is a form of cant slang used in Britain by some actors, circus and fairground showmen, professional wrestlers, merchant navy sailors, criminals, prostitutes, and the gay subculture. There is some debate about its origins but it can be traced back to at least the 19th century and possibly as far as the 16th century. There is a long-standing connection with Punch and Judy street puppet performers, who traditionally used Polari to converse. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polari [3] The Surrender of Silence p.87 [4] Described by Gurdjieff in his semi-autobiographical book, Meetings with Remarkable Men [5] The Surrender of Silence p.61 [6] See Cherry Gilchrist, Tarot Triumphs, (Weiser Books, 2016) Chapter Five Cherry Gilchrist  Author Colin Wilson first made his reputation as an “Angry Young Man” in 1950s London where he spent time in the British Museum reading room and the cafés of Soho. Members of the group remember him being around although he wasn’t involved in the group itself. Alan Bain recalls meeting him in the Gyre and Gimble – “we met just the once, but it was a memorable occasion, as a fight broke out while we musicians - about five of us that night - were playing at the other end to my usual spot. Colin managed to stand aloof and out of it.” In Colin Wilson’s second and most autobiographical novel, Adrift in Soho, he introduces several characters involved in the esoteric life. One such is Major Noyes (a pun on major noise?), a rather bombastic book dealer with “the best collection of occult books in London.” He offers the hero a glass of mandrake wine, and asks him if he is a student of the occult: ‘Not exactly. It interests me…’ Adrift in Soho (New London Edition, 2011) p. 53 (MacGregor Mathers was a British occultist, one of the founders of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and author of The Kabbalah Unveiled). Another fascinating character is the beggarly Welshman Danvers Reed. The hero first meets Danvers at the house of Major Noyes, where Danvers is negotiating the purchase of a book written in Hebrew. “Still living in that lavatory?” Major Noyes ask him. “Everybody lusts after self-approval. Everybody wants to be admired and envied by his fellows. So what use is all the talk about salvation? Nobody wants to be saved. Everybody wants to feel important. So I made a vow that I’d try to save myself from lusting after the approval of fools. I never wash. I never change my clothes. [...] This makes people hate me. So I’m never tempted to think well of my fellow men.” Adrift in Soho (New London Edition, 2011) p. 171 Danvers turns out to be a follower of the Ancient Greek Cynic philosopher, Crates of Thebes.

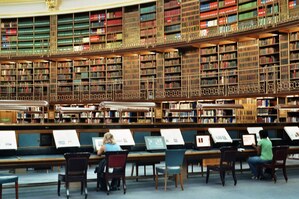

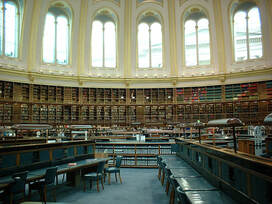

Other characters in the book include a lady expert on the cult of Mithras (who also seemed to hold strong ideas on the wickedness of Buddhism), Ironfoot Jack, the uncrowned king of the bohemians, Theosophists and Hindus, and a Yoga practitioner on a circle line train. Adrift in Soho is well worth a read for a flavour of the times. You can also watch a new film adaptation of the novel directed by Pablo Behrens. For more information visit the Adrift in Soho Facebook Page. Rod Thorn  A typical working diagram of the Tree of Life (not from 'the Group' itself' with names of Sefiroth, Hebrew letters and colour attributions A typical working diagram of the Tree of Life (not from 'the Group' itself' with names of Sefiroth, Hebrew letters and colour attributions From the coffee bar to private groups The gatherings of budding Cabalists in Soho cafes were only the outer face of ‘the Group’, in the late 1950s. Those who showed a serious interest in pursuing it further would be invited to a private meeting, in someone’s flat or a rented room. Keith Barnes recalls: ‘Everything was kept very quiet, and it was very hard to find out anything. Even the existence of the group was hidden.’ Then, one day in the coffee bar, someone slipped him a piece of paper with date, time and address on it: ‘Turn up if you want to know more.’ He did – the meeting was at the flat where Walter Lassally lived, and who he already knew, and to his surprise there were several other familiar faces there from the Soho scene, plus leaders Glyn Davies and Alan Bain. Lionel Bowen adds: ‘I believe the Group met in Walter’s flat before I joined but we juniors were kept separate from the others until we were judged to be ready.’ The main tasks were to work on the Tree of Life, and, correspondingly, on one’s inner being. The group studied Kabbalistic attributes, including numerology, astrology, Tarot, and the colours associated with Sephiroth on the tree. The ‘text book’ used was Dion Fortune’s Mystical Qabalah, but whereas this provided a good point of reference, the emphasis was always on personal experience and observation. In the earliest period, members were also assigned to ‘grades’, corresponding to the level of the Tree which you had attained or had awoken in yourself. Under Alan Bain’s tuition, the aim was often stated more generally as ‘to pass through the Veil’. It was a combination of the mystical and the practical. Walter Lassally recalled that ‘Group sessions were very practical, but they were intended to push you up the tree and get you through the veil. And I remember very distinctly an occasion when Alan considered that I had passed through, after about two or three years of study. It’s a spiritual journey, with realisations on the way.’ As Walter pointed out, the formation of the Tree itself helps this process: ‘If you associate Netzach with emotion, and Hod with intellect, this is very helpful, and shows you that intellect should balance emotion, but it shouldn’t control emotion.’ Walter also ran groups of his own after a few years, under the aegis of the Society of the Common Life. This taking on of responsibility has been a feature of the tradition; many of us who joined in the 1970s and 80s were soon encouraged to set up groups, rather than waiting decades to become recognised teachers. ‘The spirit of knowledge’ – or even ‘the Common Life’ as a symbol of the mind of humanity - is considered to be the guiding principle of the group, so that a group has a leader rather than a guru. Numbers were kept small – the old saying is that it takes seven to create a group with its own soul and dynamic, but again Walter recalled that ‘the whole thing was very small, very private. There was no sort of proselytising.’ No more than ten people was the norm. Teachers and group leaders never took money for running the groups, though expenses were covered by donations, as can be seen in pages from Walter’s logbook of the time (1962-3). Norman Martin also remembers some of the practical procedures. A group would start by talking about the tree and its correspondences. Then members would be put into grades corresponding to the Sephiroth, and people would progress from one to the next. Generally speaking the progression wasn’t by ritual but by simple acknowledgement. However, sometimes there were more ritualistic, even dramatic occasions set up to propel the seeker across the threshold. Norman’s own initiation into the group was made rather mysterious. He was told that he had to meet ‘the Goat’ on the London Embankment in the middle of the night. The Goat turned out to be Alan Bain, by dint of his being a Capricorn, and together they walked and talked until Alan eventually declared that the moment of initiation had come. He raised his hand, and that moment, by synchronicity, (or perhaps by careful timing!), Big Ben chimed. Norman was in! Not everyone was happy about stepping higher up the tree – a tale is told about a young French lad who pleaded to be allowed to progress to Netzach, but when granted his wish burst into tears and asked to be taken back to Hod. Keeping a sense of humour was important, and there were all sorts of sayings bandied about, such as ‘Funny how it works!’ ‘You’re quite bright, you work it out!’ and ‘From the sublime to the gorblimey.’But although entertaining incidents are recounted with a chuckle, looking after the welfare of the group was also a priority, and in general, people weren’t pushed further than they wanted to go. There were two other main sources of study for group members. Getting a reader’s ticket to the British Museum Library was a must for some, including Glyn Davies and Alan Bain. The iconic, circular reading room in the British Museum (now replaced by the separate British Library) was a magical place in its own right. You had to apply with a reference from a serious scholar – being a registered student or just an interested member of the public wasn’t enough. Alan Bain managed to get his reference from Geoffrey Watkins, son of the founder of Watkins Bookshop. (a very good history of Watkins, which played such a part in the education of many Kabbalists, is given here). In Alan’s memoir, (see here) there is an excellent account of what it was like to penetrate the holy of holies, and to summon up books from the hidden depths of the library. As Alan affirms, this was a place to find real classics of esoteric literature, including works by past masters such as John Dee and Robert Fludd. However, the aim was not so much to lose yourself in old magical tomes but to ‘get yourself an education’, not perhaps in the conventional sense, but to develop a sense of how the river of knowledge had flowed down through the centuries. The training helped people to look beneath the trappings to the message or understanding conveyed in earlier writings. The other input came directly from the School of Economic Science and the Study Society. Glyn Davies and a few others were members of these organisations as well as ‘the Group’, and through Glyn’s connections, SES agreed to offer a programme of study which could be followed in the group. SES training emphasised intellectual and philosophical approaches, and introducing this material into the group was probably aimed at strengthening these abilities. It would round out the training, so that members could operate in a more detached way if necessary, and not rely solely on intuition and psychic experiences. Although SES gave this permission, rumour had it that they had also planted ‘a spy’ in the group in the form of Richard Henwood! Richard, although liked by everyone who knew him, eventually found the pressure of this combined approach too much and had to leave, although he remained affectionately in touch with various group members until the end of his life.

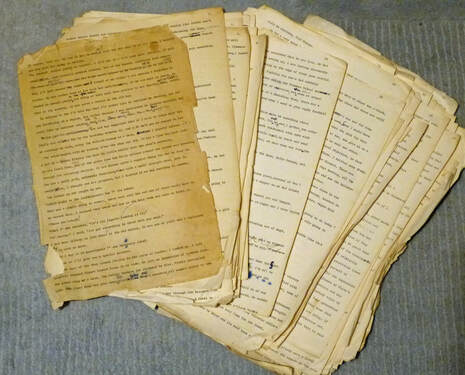

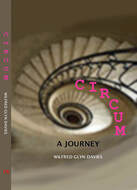

Note: Richard Henwood wrote an unpublished novel based largely upon his experiences in the Group. Despite searching, and despite several contacts having seen this novel, we cannot find a copy, but would very much like to see it if anyone can supply this. Eventually, the Soho days came to an end. Eventually too the ‘Group’ was replaced by other developments – Alan Bain left London, and later took his work into the arena of the Independent Catholic Church and the Theosophical Society. Tony Potter began his own line of teaching in North London, under the name of ‘The Society of the Hidden Life’, with particular emphasis on the ‘stop exercise’, which he developed as a key practice. Walter Lassally became too busy with his work as a travelling cinematographer to run groups regularly, although he continued to work with Cabala and the I-Ching to the end of his life; Robin Amis developed his own type of teaching known as ‘The Society of the Inner Life’ in the context of the Orthodox Church, and Glyn Davies convened astrology and Kabbalah groups from the late 60s onwards, which eventually evolved into Saros. It’s easy to forget, given the seriousness of purpose, and the long-lasting effects of the Group, just how young these leaders were in the Soho days. Most were still in their twenties, and so as careers developed, families grew, and life challenges faced them, some took other routes. However, all those to whom we’ve spoken have deeply-embedded memories of the era of ‘the Group’, and a strong sense of what it meant to them. With thanks to our principal informants on the workings of ‘the Group’: Keith Barnes, Lionel Bowen, Norman Martin, and to Walter Lassally and Robin Amis in memoriam. Cherry Gilchrist  A battered copy of Glyn’s novel Circum lies in one of my study drawers. The loose foolscap pages are yellowed by tobacco smoke, and worn thin and ragged at the edges from frequent handling. It is typed, but here and there amended by hand. Some of the pages are scrawled over with notes and diagrams, most probably the first thing that came to hand when Glyn had to jot down an idea in a hurry, or wanted to explain something to a visitor who’d come with serious questions. My connection with Circum goes back to the early ‘70s, when Glyn thrust a copy at me to read, and then to type up for him, as a paid task. It went through several incarnations, with several typists, the final version as a dot-matrix print-out , probably in the early ‘90s. Glyn was by his own admission a ‘jack of all trades’ or ‘generalist’ who could and did attempt almost anything. He was variously a jeweller, an accountant, a salesman of babywear, a book dealer and a radar fitter, to name some of his occupations. He also decided to be a writer – not as a literary author, but as an exponent of ideas and a generator of stories with a mythical flavour. Circum was his one and only novel, written in the late 1960s. In one sense, it’s a traditional boy-meets-girl, then-meets-another-girl kind of story. In another, it’s an account of entering a spiritual path. And thirdly, it’s a fascinating snapshot of life in post-war Britain. According to Glyn, it was partly (but only partly) autobiographical. And according to one of the early group members (Norman Martin, who trained Glyn in jewellery-making), Glyn went on a kind of self-imposed retreat to write the book. He rented a tumbledown cottage for a few months in the Mendips. ‘It was just a pile of stones…,’ Norman recalls. Glyn used his time in the Mendips to try out caving, something that features in the novel. He liked to experience what he was going to write about. The novel has twenty-two chapters, and Glyn told me that each one is based on a Tarot card (there are twenty-two cards in the Major Arcana of the Tarot). But which is which? Ah, that’s left to the reader to discover! And my guess is as good as yours, except for one chapter which Glyn did tell me represents the Empress. After Glyn’s death, I decided that it was worth getting Circum into print. Other books of Glyn’s had been published, but not this one. With the permission and help of his family, I prepared a print-on-demand edition. And editing it was quite a task! Glyn did not bother with the finer points of punctuation or consistency, even though he was a good wordsmith. I found myself having to decide whether the hero was really heading for the docks at Liverpool, as first stated, or Southampton, as on the next page. But it was a rewarding task, and the resulting copies were ordered by well over a hundred of his acquaintances. Now plans are being considered to produce an electronic version, which could be made much more widely available. Towards the end of Circum, Charles Hawton, the hero, begins to forge a proper relationship with Fenella, a girl from the East End of London. Fenella is a chirpy Cockney sparrow, sometimes frivolous, but the reality of the understanding they have at a deeper level begins to emerge. Read on.....the extract follows below... ‘And there’s me. When I was a little girl, I used to dream of knowing everything, and I still just want to know. Mum says I’m a bookworm, but I’m not really. Sometimes I like books, even books on astrology.’ She laughed out loud.

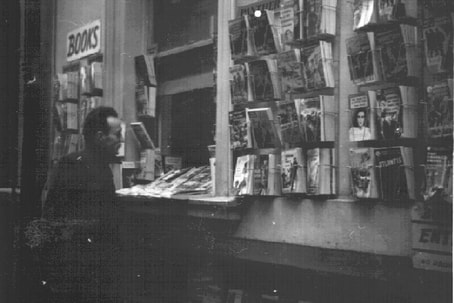

I remembered John Britten’s shop, and then I was laughing too, a little ruefully I must admit. ‘Anyway,’ said Fenella, ‘I always wanted to talk proper, and I used to mimic the teachers and the radio-announcer and the Methodist Minister. Mum wasn’t religious - she used to send us to Sunday school because, she said, “Some of it’s just good common sense.” She’d ask us what we’d been told there. Dad was a Mason, I think, though I’ve never seen any of his paraphernalia. At school I did well at art, and went to art college, but I didn’t think I’d ever be any good, so I took a secretarial course. The rest you know.’ What did this matter? Here was reality. The trappings were not important. She tended to seek out well-known people, and her culture was a little stiff and pompous. She dressed very fashionably and could become cockney shrewish, but she herself left me feeling easy. The layers over the essential Fenella just did not matter. It is curious that where there is love, there is no need to forgive foibles and habits. They just don’t really intrude. I tried to say something of this to her. She grew thoughtful. ‘Sounds silly, doesn’t it, but I feel as though I wear many skins, like an onion. Oh I dart around, and talk of clothes and I gossip, but that’s not me you know.’ This caused me to smile. I of all people should surely know this. ‘Do you think that you are anything particular?’ I asked. ‘No, the “me” doesn’t change. The things about me do - my clothes, accent, how I react - but me, I’m still the same as I was as a little girl, playing in the back yard and climbing on the wall to wave to the trains. Or even meeting you for the first time.’ My mind flashed back to the bookshop which I saw with a strangely familiar clarity, as if it would be that way for always. She stood there, looking at me. I was sitting behind a roll-top desk covered with books. Behind me were shelves with valuable stock, dusty volumes, leather bound and embossed, and with that slightly acrid smell, that probably comes from fish glue and animal hide. The shop door opened and this smiling small waif stood there and tentatively asked, ‘Do you stock books on astrology?’ I just gestured to her, and went on reading. Then some gateway opened, and my own memories began to surface. Standing in open-mouthed astonishment because the little bird I held in my hand, which was caught by my grandfather in his netting trap, was pecking me furiously. Drawing and colouring an apple, a glorious red shot with green and fat like bursting, when I was only four. A new suit I didn’t want to wear. My parents upset because I wanted to do everything for myself. Guiltily selling a pet jackdaw so that I could buy a model train that worked. It was brass, with a space for a real fire which could get the steam up. Sitting in the dust by the roadside, making imaginary castles while people in clogs and supply carts passed me, coming in from the country. My feeling of frustration because I never asked the right questions or, if I did, people didn’t understand me. The eternal moments when I stood on a bridge and watched the fishes swim. And then, behind these memories, another place where I lived a different life. I think that children really do live in another world, next door to this world but maybe only half an inch away, where they make kings and oceans, ships and savages. I told Fenella what I thought. She said delightedly, ‘Yes, yes, and you used to make little worlds and big worlds and have all your own stars. You didn’t have to believe in any of them - they were just there, and when you finished, you could put them away and bring them out again, like toys from the cupboard. ‘I used to have a friend; he was an eagle. He came from a high, high mountain far away, and he could fetch me anything I liked. We talked together before I could talk to Mum and Dad. But he went away one day, and I began to grow up.’ (Circum pps 135-7) Cherry Gilchrist  The meditation room at the Saros Centre, Buxton (1980s) The meditation room at the Saros Centre, Buxton (1980s) From the early days of groups, meditation has always been a key element of individual practice. The first type of meditation practised by most early group members was TM, or Transcendental Meditation, which came from a direct involvement with the School of Economic Science, who hosted the Maharishi on his first visits to London in the early 1960s. Over the years, however, the pattern changed, and the main forms of meditation practised by individual group members have included Buddhist, Christian, and Kabbalistic practices. Many group members have come to consider meditation as the central pivot of their spiritual path. In her recent memoir about developing her own spiritual understanding under the teaching of Glyn Davies, Lucy Oliver describes meditation thus: ‘As Glyn presented it, the essence of meditation is the engagement and holding of a mental object, which can be a sound, image, or movement like walking. As the mind stays with this object it gradually magnetises all the mental movements, flurries of thought and feelings, associative chattering etc. towards a single vector, rather like iron filings turning in one direction. And so random thought activity tends to die down, and settle, not so much around, as near the object, which itself gets finer and finer as does the breath. The seed-object can disappear, or hover on the edge of awareness, and pure consciousness rest within itself “like fine wine upon its lees.”’ Tessellations, Lucy Oliver, p.51 Cherry Gilchrist ‘The Group’ in Soho In the 1950s, London was there for the taking. It was bomb-damaged, impoverished and dirty, but it was also cheap, cosmopolitan and – in the area of Soho – a stimulating environment. Anyone could make their way into this raffish district and hope to get by. Here, you could drift around the cafes, make friends, maybe find casual employment and somewhere to doss down for the night. Those who became members of ‘the Group’ mostly arrived this way. The coffee bar scene, characterised by the hiss of espresso machines, and the steam of frothy milk, was growing fast. One Signor Riservato, a dental-equipment salesman from Italy, was the unlikely founder of this craze. Arriving in England to sell his wares, he was disgusted by what passed for coffee here. He switched his stock to sell Gaggia espresso machines, and opened his own café, the Moka Bar, which was the first to kick off the Soho coffee bar craze.[i] The founders of the Group - Alan Bain, Glyn Davies and Tony Potter – held court, singly or together, in a few selected coffee bars. ‘The Florence’ and ‘the Cross’, both in in Villiers St by Charing Cross, and the 2 Gs (The Gyre and Gimble) were favourites, although Lyons Corner House was also a regular venue, perhaps because of its cheap eats. Even budding Kabbalists could not live on coffee alone. ‘You could have Spag Bol for 2s 3d round there,’ reminisced early group member Keith Barnes fondly. Then there were cafés known more as the haunts of musicians, such as the Nucleus, nicknamed ‘the Nuke’, which also became part of the circuit - Alan Bain was himself a musician, playing the accordion professionally. Other ‘creatives’ from the world of advertising and film-making also began to frequent post-war Soho. Two of the early group members worked in an advertising agency, and Walter Lassally, who was then at the start of his distinguished career as a cinematographer, found the embryo ‘Group’ while visiting Soho, quite possibly in connection with film shooting or post-production studios. ‘The Nucleus was the centre of it all, the coffee bar in Monmouth Street. And someone was always in there holding forth, mainly Potter. Potter was great at holding forth, whereas Alan was really quite reticent.’[ii] Musicians turned up on the fringes of the group who were already rising stars, or about to become so: Red Sullivan, Davy Graham and Diz Disley hung out in cafes where Tommy Steele was also beginning to make himself a name. Keith Barnes, too, liked to busk in the musician’s cafés, as well as frequenting the more regular Group haunts. And here’s what Lionel Bowen had to say: ‘I spent a lot of time in the ‘Gyre and Gimble’ coffee house on John Adam Street close to Trafalgar Square. We drank espresso, played bad guitar and sang (poorly) folk songs. The elder members of the Group hung out there, on the lookout for likely recruits (of which I was one). My generation of the Group met in three different restaurants: Joe Lyons Corner House in the Strand, The Cross and the Florence on Villiers Street. Where we met depended on how much money we had at any one time. The Florence Cafe was the best, but we had to order a meal to sit there for any length of time. We read The Mystical Kabbalah, traded lists of attributes with each other and fixed the world, as young idealists are prone to do.’ Exciting times! Soho society then was a mix of truth-seeking youngsters, creative artists and original thinkers, but along with that went prostitutes, heavy protection rackets, and homeless runaways, many of whom were in trouble.[iii] Group members took their responsibilities seriously: ‘Some of those we met in the cafes were young girls who had run away from home or were wanted in court. Usually we managed to talk them into going back home, or facing up to whatever they were running away from,’ Keith Barnes reported. And the members themselves often lived hand to mouth. In a way, this was part of the Bohemian tradition that had also coloured Soho before the war – not being tied down, taking a berth for the night wherever you could find it, scavenging for cheap or free food and earning money only when you had to. The recently-discovered memoirs of Ironfoot Jack, himself a colourful character with a vague interest in Occultism, paint a vivid portrait of Bohemian life and getting by in Soho in the 20s and 30s.[iv] Sleeping out and living rough did carry a certain romanticism. Even the writer Colin Wilson, who had a passing association with the Group, slept out on Hampstead Heath, making sure his photograph was taken there. Ernest Page, who taught Alan Bain and other Group members astrology, was often homeless, and died on a park bench. He was a man of many parts, however, as an accomplished poet and a key helper in what became the Simon Community, a charity supporting London’s homeless people. If Keith Barnes was short of a bed or a friend’s floor to sleep on, he would usually go to one of the all-night cafes. Mick’s in Fleet St was a favourite. ‘You would often see quite famous musicians bombing along there in Ford vans driving at 70mph delivering newspapers – they took on these jobs because they couldn’t earn enough from their music.’ [v] Keith and Glyn Davies shared several flats together, just about making ends meet. Keith recalled how they would go and scrounge a bone ‘for the dog’ from Smithfield, then head to Covent Garden late afternoon to pick up fruit and veg from the ground, which was there for the gleaning. Glyn always had a pot on the go, into which he would throw the bone and the veg. ‘Very tasty!’ Rented rooms were usually very basic: in Kentish Town Keith and Glyn were plagued with mice, but Glyn used to leave the oven door open to keep the mice warm at night! Sometimes people made shift in more unorthodox ways Alan Bain slept in a kind of office that he rented near Charing Cross, and folded up his blankets every morning so that the landlord wouldn’t know. Occasionally, dawn saw a few Group members heading off to Brighton on the earliest train for a quick frolic by the seaside – once, in Glyn’s case, to plunge into the waves with the aim of shrinking his new blue jeans! An old type of train fare, formerly known as a ‘workman’s ticket’ and now re-named an ‘early morning return’, made such jaunts possible for cash-strapped Group members.[ For those not on a career path, such as advertising or film-making. paid jobs were generally taken out of necessity, though sometimes interesting in their own way. Both Alan and Glyn became book-sellers. Alan recalled that he opened “Bain’s Bookshop” in a room above the Gyre & Gimble with £24 pounds borrowed from Glyn. And Glyn ran a portable bookstall, using wheelable book cases, and sold his books late into the night, after the shops closed. His regular pitch was outside St Martin in the Fields, but he also plied his trade outside Foyle’s bookshop. One night, its owner, Christina Foyle, emerged and, much to his surprise, asked him politely how business was going! Sometimes, however, more mundane jobs like dishwashing or clerking in an office had to be taken up. On one occasion, Glyn announced to his flat-mate Keith, that he had a job interview the next day. The only problem was that he only had one outfit - Keith was asked to get his suit and shirt cleaned while Glyn stayed put, wrapped in a blanket!

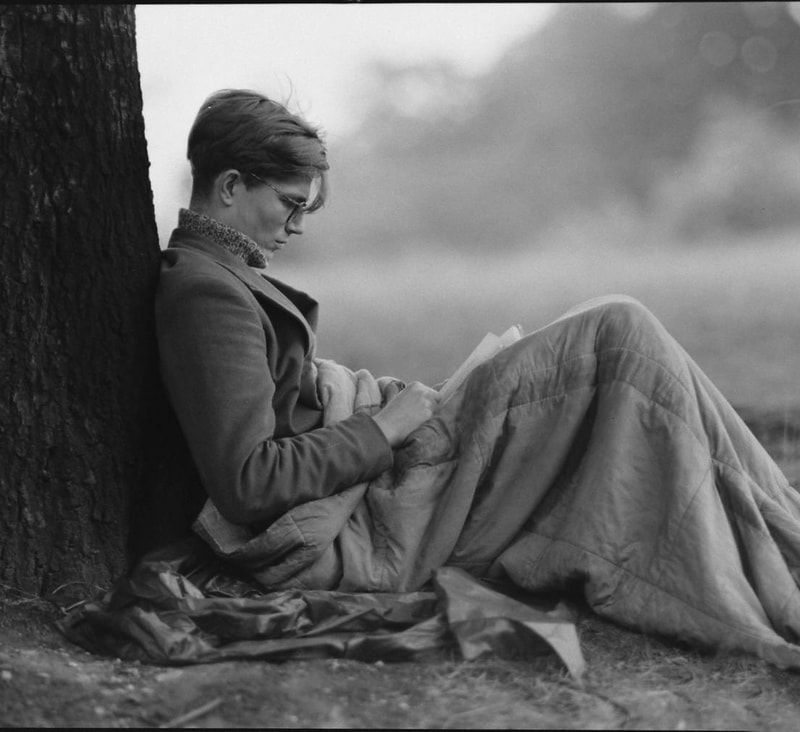

So the coffee bars were not only places to hold philosophical discussions. They were where you could get warm, have something cheap to eat, and pick up tips about jobs, musical gigs and rooms to rent. And perhaps do a little bit of good for those who were looking lost. ‘In the coffee bars or at gatherings, if someone came along who just needed ten shillings to get home, then the advice was to give it to them. Help them on their way. But if they came back, looking for something, and showed interest, then you would introduce them to another member of the group.’ (Keith Barnes). No one was pressurised to join the Group, although Tony Potter could be very persuasive. ‘Tony was a kind of front man, fond of holding forth, especially in front of adoring young women’. (Walter Lassally). And what if you did join? Well, for a while you might be just a part of the mix, turning up at one of the coffee bars, joining in the debates, and learning a little about Kabbalah and astrology. Then, when you w[i]ere judged to be ready, you would be handed a slip of paper with a date, time and address on it. And, as the old saying goes, ‘This is then the work really begins.’ Cherry Gilchrist Part II will explore the workings of the early Group behind closed doors. i Article by Dr Matthew Green: ‘Coffee in a Coffin: The fascinating story of Le Macabre – and Soho’s 1950s espresso revolution’. Daily Telegraph Mar 9th 2017 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/united-kingdom/england/london/articles/the-amazing-story-of-soho-1950s-espresso-revolution/ iinterview with Walter Lassally, Suffolk 2014, by Rod Thorn and Cherry Gilchrist iii For an overview of Soho at the time, I recommend Soho in the Fifties by Colin Farson (Michael Joseph, 1987) iv The Surrender of Silence: The Memoirs of Ironfoot Jack, King of the Bohemians’ edited by Colin Stanley (The MIT Press, 2018) v Recollections shared by Keith Barnes during several conversations with Cherry Gilchrist. Cherry and Keith were members of a Kabbalah group together, run by Glyn Davies, 1970-72. Cherry Gilchrist |

AuthorsArticles are mostly written by Cherry and Rod, with some guest posts. See the bottom of the About page for more. A guide to all previously-posted blogs and their topics on Soho Tree can be found here:

Blog Contents |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed