|

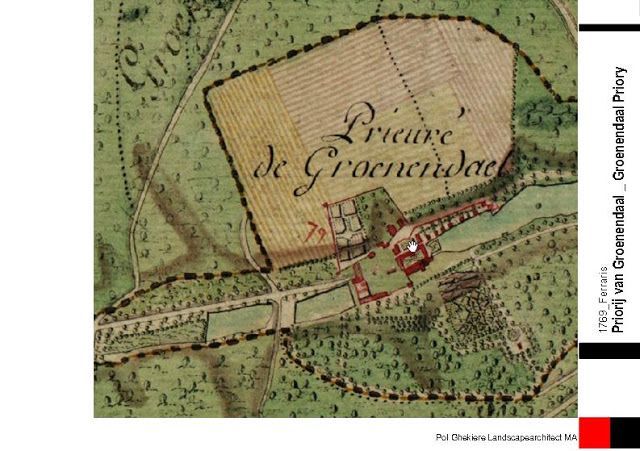

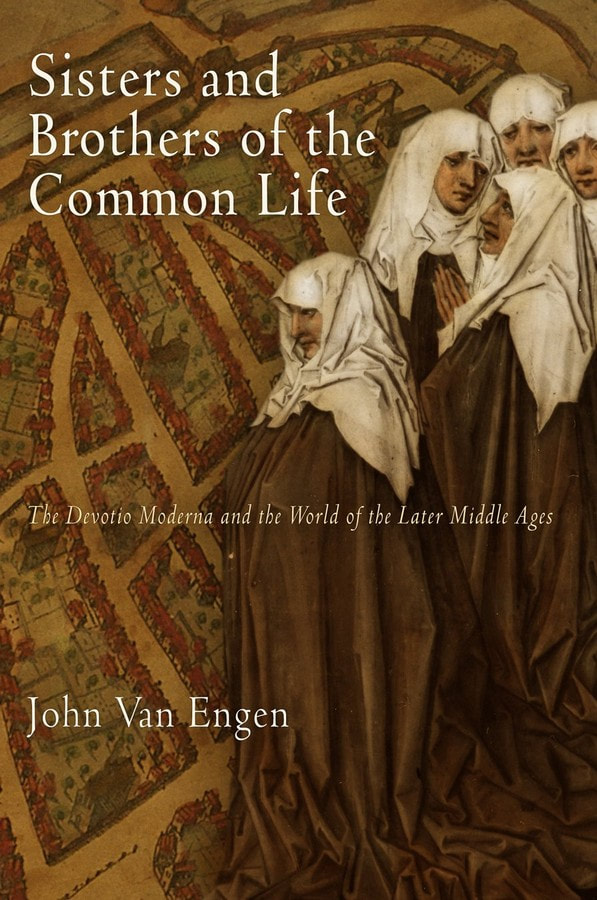

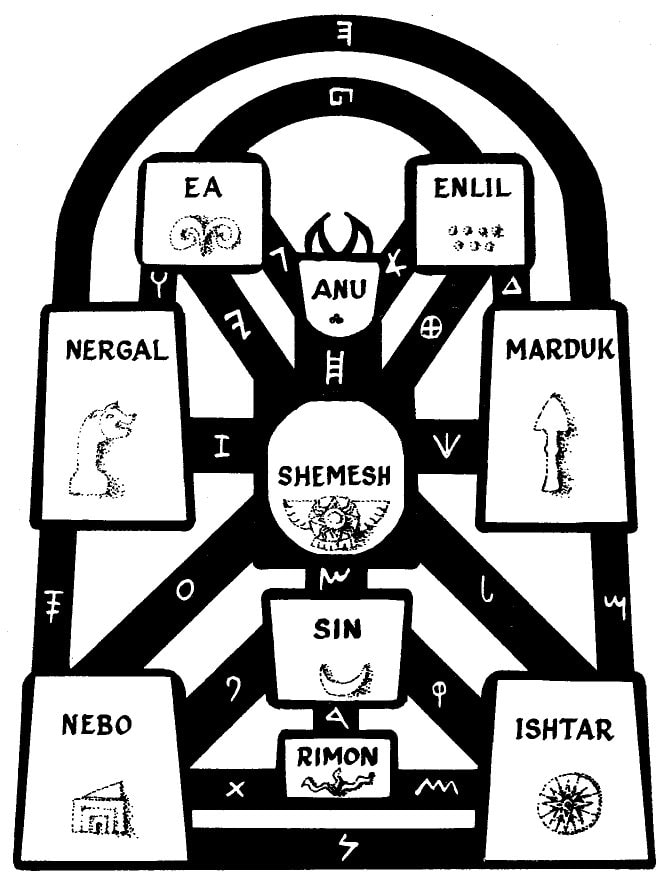

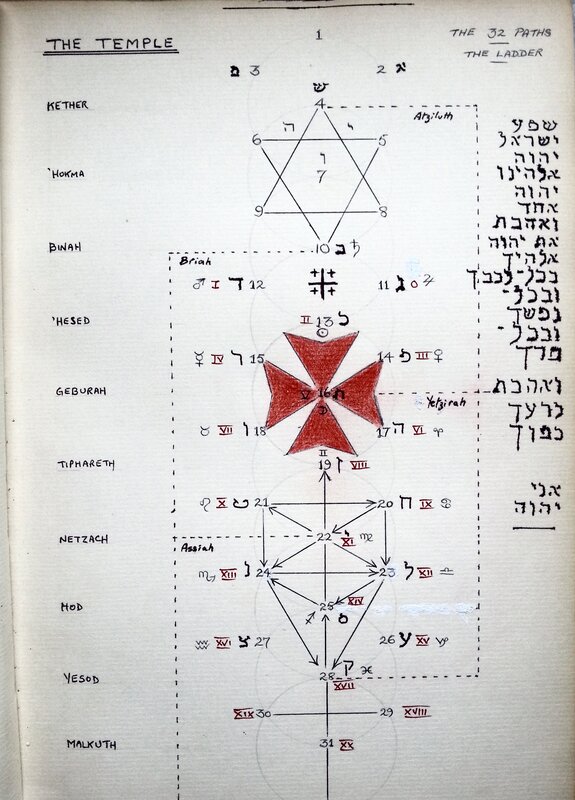

‘The Society of the Common Life’ The early Kabbalah groups in Soho and their successors elsewhere were often run under this name. Why so? And where did the name come from? Although we don’t have all the answers about how it was introduced into the groups, it was always said that our lineage was descended through the original Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. This was a movement initiated in the 14th century in the Low Countries of Europe, to allow men and women to practice a Christian ‘mixed life’ of work, study and contemplation in a communal fashion, without taking holy orders. In the first part of this account, I’ll set out its history and what we know of the practices of the Brothers and Sisters, plus the significance of Common Life itself. Then in the second part, I’ll return to questions of how and why this lineage was affirmed in our groups. Ruysbroeck The story starts with the 14th century Christian mystic known as John of Ruysbroeck (also spelt Ruysbroek, Ruusbroek), who was the inspiration for the founding of the ‘Common Life’ movement. His written works are still renowned today, and are imbued with a deep understanding of the stages of spiritual progress and the levels of contemplation. (For a series of quotes from his writings, see here ) Ruysbroeck was born in 1293-4, in a village of the same name, situated in what is now Belgium. His mother was a single parent, his father unknown. He left home when he was eleven, to live in Brussels with his uncle Jan Hinckaert, a priest, and his colleague Frances von Coudenberg. As the years went on, they formed a small and closely-bonded spiritual group, described as ‘a veritable mystical association’. Ruysbroeck was also formally educated at the Latin schools in Brussels, and in 1317, he was ordained as a priest. But in 1343, he and his two fellow seekers applied to take over the nearby forest hermitage at Groenendaal, in rural isolation. Here they built a chapel, and tried to live a life of quiet contemplation. However, they were apparently plagued by the duke’s huntsmen, and their excessive demands for hospitality. For this reason, they eventually decided to place themselves under the rule of St Augustine, as ‘regular canons’, which gave them some protection against intruders. Ruysbroeck and Kabbalah Many visitors sought Ruysbroeck out in the hermitage, though for better reason than the huntsmen: asking for spiritual guidance, and sometimes to join the order. Ruysbroeck had begun writing mystical texts before he left Brussels, and was already renowned for his wisdom and insight. As already mentioned, his books are still revered today as classics of Christian mysticism. They are a combination of offering a structured approach to stages of spiritual development, but also of showing the way to the transcendent, soaring into the realm of what he called the ‘wayless’, leaving behind both images and explanations. It’s clear from his writing that he was informed both by his own experience, and by drawing upon some kind of existing philosophical framework which he then developed. The exact sources remain unverified, though they probably include Meister Eckhardt (who may even have been an acquaintance of Ruysbroek’s), along with Neo-Platonic teachings, and quite possibly Kabbalah, which could have been transmitted via the 12th and 13th c. Spanish Kabbalistic schools. His use of symbolism, his structuring of spiritual experience, and his specific description of the Seven Gifts of the Spirit, certainly accord more closely with a Christian form of Kabbalah than with Neo-Platonism. This is expanded in his major work, The Spiritual Tabernacle, his magnum opus in terms of symbolism. Gerard (Geert) Groote (1340-1384) It is Gerard Groote of Deventer (now in the Netherlands) who then takes the story forward into what was to become the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. In 1377, Groote came to Groenendaal in order to visit Ruysbroeck, and stayed there for nearly two years. The two men had never previously met, but legend has it that Ruysbroeck seemed to be expecting Groote, and greeted him like an old friend. Whatever the truth of legend, (and there may well be some), the transmission of some kind of spiritual inspiration from Ruysbroeck to Groote is generally accepted by historians. Groote came again in 1381, just before Ruysbroeck died, as a very old man in his late 80s, and Groote himself died only three years later, while still in his 40s. Between the two visits, Groote initiated a whole new course of action. He opened his house to those poor women of Deventer who wanted to lead a spiritual life, and (probably with his male follower Florence Radewijns), founded houses for the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, and what were to become very important part of their work - schools for children. The Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life from then on became known as educators, and the network of their schools spread throughout Europe. Groote himself became known as the founder of the ‘Devotio Moderna’, a simpler, more direct and pious form of worship than had been practised in that era, and a precursor of the Reformation. Deventer itself was a well-established trading port on the River Ijssel, and became a member of the important Hanseatic League, a trading and defence guild for merchants. Its Latin School was established in 1300, and the town became associated with both education and, slightly later, with printing. It seems a natural home for the first efforts of the Brothers and Sisters to study, copy manuscripts, and educate. Groote’s old home is now a Museum named for him. Gerard Groote's old house, now a Museum. These figures probably represent a Sister and Brother of the Common Life. Although Ruysbroeck and Groote seem to have been very different types of men – Ruysbroeck more mystical and compassionate, Groote zealous and upright in his moral resolve - the link between them was strong, and the key concept which united them was that of Common Life. So it is this that I will now move on to. The term Common Life To him now is shown the Kingdom of God in a five-fold manner. Since the external, sensible kingdom is shown to him, in the same way too the natural kingdom, the kingdom of scripture, the kingdom of grace above nature and scripture, and finally the divine kingdom above grace and glory is also shown. For to have all these things clearly and lucidly known and ascertained, is called common life. The Kingdom of the Lovers of God – John of Ruysbroeck, Chap 37 Ruysbroeck’s description of Common Life here is key to understanding its meaning, both for him and in a more outward way, for members of Groote’s Common Life movement. Its aim is to unite practical life, learning and study, and contemplative experience of the divine. In Ruysbroeck’s terms, it is a precise path of knowledge, with five levels to its ‘kingdom’: the outer world of the senses, the ‘natural’ level of nature and life forces, the level of sacred learning, then that of grace, and ultimately the divine and formless realm beyond that. The Common Life movement did practice spiritual exercises – more about this further on – but their main emphasis was on uniting action and contemplation while living a ‘common’ life together. The Brothers and Sisters shared their worldly goods and lived communally, aiming to unite outward work and acts of charity with practices of meditation and prayer. They also placed emphasis on the individual’s own relationship with God, refuting the notion that it could only be offered via a priest or by taking holy orders. Historically, this was a time of arrogance and corruption among the priesthood and monastic orders, and this stance of The Common Life movement prefigured and indeed influenced the Reformation, including its leading figure of Martin Luther. The Path to the Mountain The Brothers and Sisters sometimes took holy orders, however, mainly for the kind of reasons that Ruysbroeck and his followers did – to avoid persecution of one sort or another, and so that they could work freely towards their goals. The Congregation of Windesheim, founded in 1386, was one such development, of which the famous mystic Thomas a Kempis was a member. He is best known for his book The Imitation of Christ, which ‘is perhaps the most widely read Christian devotional work next to the Bible, and is regarded as a devotional and religious classic. Its popularity was immediate, and it was printed 745 times before 1650.’ (see more here) The followers of the Common Life also produced various written works and teachings over the years, and although these vary considerably with individual authorship and practices of different ‘houses’, there are some strong themes which emerge. One of particular interest is how they described the journey towards God as that of finding our path back to the holy mountain, from our exile in the valley. Gerard Zerbolt, one of the first members of the congregation of Windesheim, described how we have forgotten that the mountain is our true home, and have lost our way in a valley located in a distant land. Therefore, he says, “a great labour” is needed in order to return. This is more than a pious sentiment; it is clear that spiritual exercises were practised by the Brothers and Sisters, to undertake this ‘labour’. Note that this corresponds well with the term ‘the Work’, as used by the Kabbalah groups, to define the task of acquiring knowledge and achieving self-transformation. Although there are other sources for this, such as ‘the Great Work’ of alchemy, and ‘the Work’ of students of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, nevertheless it has a strong correspondence with the practices of the Kabbalah groups, along with the notion that we are on a path of ‘return’, climbing the ladder of the Tree of Life. And as for the ‘Holy Mountain’, we will meet this again in a forthcoming blog on the Dutch Astrology tradition, connecting to the Soho Tree lineage. The Schools of the Common Life The chief ‘outer’ work of the Brothers and Sisters began by taking paid work copying books and manuscripts, but then evolved into the field of education. Many schools were established and maintained under the tutelage of the Brothers of the Common Life over the following hundred years or so in the Low Countries, Germany and even further afield. The influence of these schools was enormous. Erasmus was one of their noted pupils, as were Luther and Nicholas of Cusa; even a future Pope (Adrian IV) was trained there. Roles and Gender within the Brethren of the Common Life In the Brother and Sister Houses, goods were held in common, and a common way of life was practised by all. However, Groote respected people’s individual gifts, and persuaded individuals to find the best occupation for their spiritual progress. For instance, he encouraged John Cele, the head of the school at Zwolle, to stay in his job rather than take holy orders. Women were – more or less – on a par with men; houses tended to be single sex, though there are records of at least one married couple living there. However, Groote himself seems to have been wary of women. Although he helped many women, first of all by opening his own house to poor single or widowed women, he avoided contact with the female sex as much as he could, and saw marriage primarily as a means of procreation and controlling lust. The Way of the Common Life But however effective the Brothers and Sisters were in living a pious and productive outer life, they considered the inner path to be of supreme importance in fostering ‘the common life’. I’ll now give a summary of what appear to be the main ingredients of this aspiration to attain ‘common life’. Five-fold kingdom The work for both Ruysbroeck’s and Groote’s followers combines contemplation and action. As we’ve seen, according to Ruysbroeck it demands an effort to attain knowledge of the ‘five-fold’ Kingdom of God, in their forms of matter, nature, scripture, grace and divinity. All five parts of this kingdom must be experienced to attain to this ‘common life’. Members of one body It corresponds (to an extent) with the view that all men are members of Christ’s body, the One Man, which can perhaps be likened to the perception of Adam Kadmon, the Great Man, in Kabbalistic terms. The individual’s connection to God It defies any monastic claim that man can only come to God through a member of a spiritual hierarchy, in particular via priest, ordained monk or nun, or that this is a path only for males. Self-perfection is possible for a human being. It is our birthright, and even our duty, to seek the ‘impress’ of God within our hearts. Conduct The person on the path should be humble, kind to others, abstemious but not austere. Life should be a mixture of contact with the world, and retreat from it. It is sometimes described within the brother-and-sisterhood as the way of Mary and Martha, both aspects being important. In the common life, an individual should practice both an inner and an outer trade. If you trade on the street, you must also service your ‘inner workshop’ The need for spiritual exercises Exercises and special actions are necessary for this. According to what we know of the practices of the Brothers and Sisters, these include:

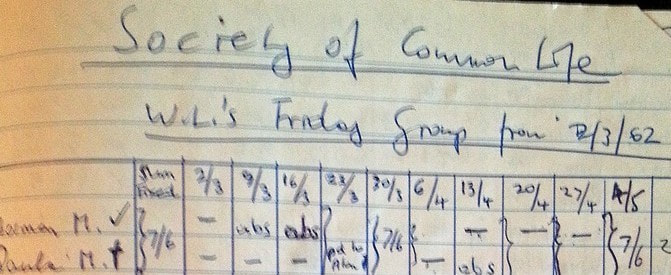

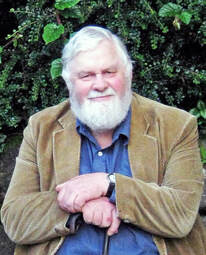

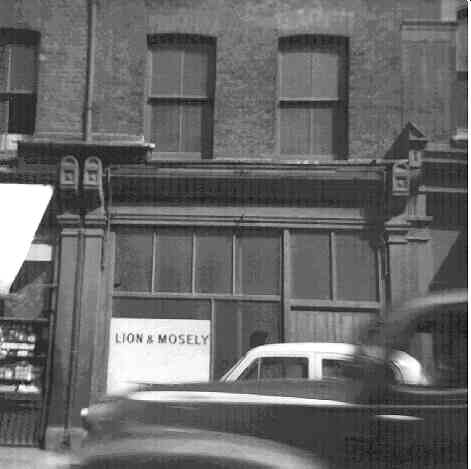

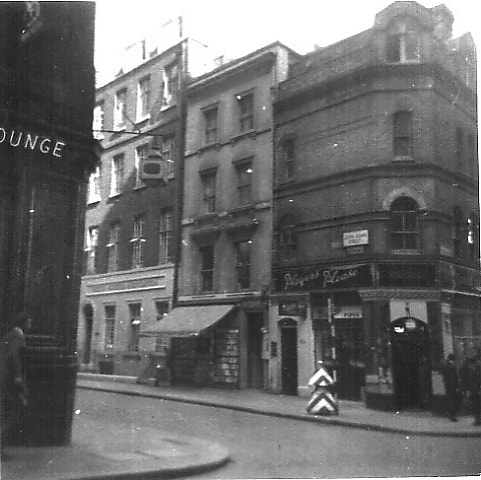

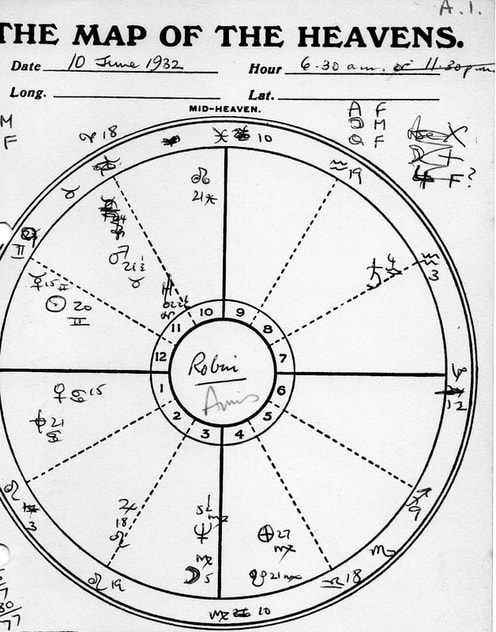

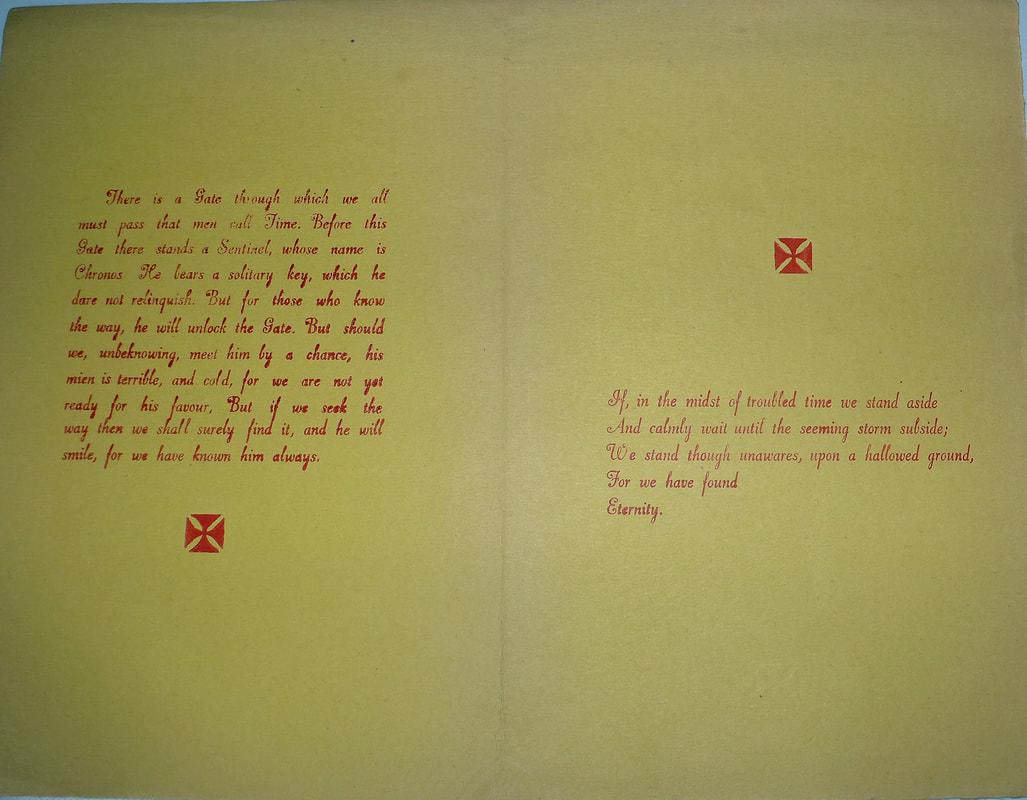

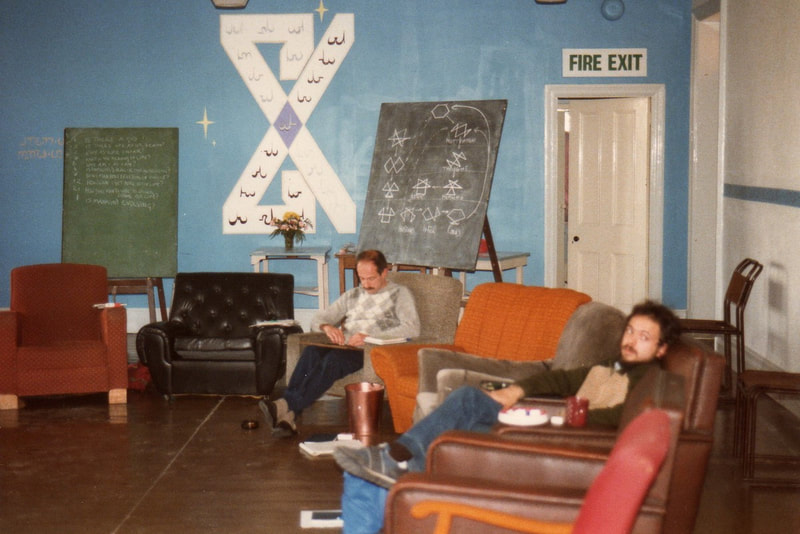

Some practices may involve an advanced level of contemplation, whereas others require outward acts of remembrance: the Brothers, for instance, ‘paused and prayed whenever they heard the church bells ring’. They also sought to “prevent” each activity with a brief prayer to clarify their direction’. (Perhaps this is something similar to the Gurdjieff ‘Stop’ exercise?) Examples of these practices can be found in the writings of Ruysbroeck, Groote and his followers, Erasmus, Thomas A Kempis and the English Platonists, though much more remains to be done to extract them from the texts. Some are stated openly, whereas other methods may be couched in descriptions of mystical experience which seem to suggest specific exercises. So it’s clear that both Ruysbroeck and the followers of Groote, ie the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, knew a range of exercises which involved both body and mind, and which could be practised as contemplative or within the context of active life. It also seems very likely that all this was underpinned by a structured mystical cosmology, perhaps a version of the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. The quotes below, with which I end this account, illustrate some of these points, and also the sense of what ‘common life’ meant to these our spiritual ancestors. But first I’d like to return to the connection between the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life and the Soho and subsequent groups. The Society of the Common Life A number of core Kabbalah groups in this ‘Soho Tree’ tradition have been called ‘The Society of the Common Life’. These include the first one founded by Alan Bain in the late 1950s, and offshoots such as the broader-based Kabbalah meetings held in Cambridge from 1969 under the aegis of Glyn Davies and Lance Cousins. Acknowledgement is also given by teacher Warren Kenton , who dedicated one of his principal books, Adam and the Kabbalistic Tree, to the Society of the Common Life (1985 edition). There were also variants of this – The Society of the Hidden Life (leader Tony Potter), and the Society of the Inner Life (leader Robin Amis). Below are examples of this - notepaper heading used by Alan Bain, and a notebook of Walter Lassally's recording subscriptions paid by group members in 1962. In the group to which I belonged, we were told that our lineage had descended through the original Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. Like any family tree, there are different branches, and it may be that this was just one line which blended into the particular tradition of Kabbalah which we inherited. This particular strand of Kabbalah had apparently reached Britain from the Low Countries just after World War One, and was passed down very much on a one-to-one basis until the expansion of groups in the 1950s. However, there is one stray fact which leads to more questioning. There was also some use and acknowledgement of the name in the Study Society and its sister organisation the School of Economic Science (SES). It’s also reported that a few members of these organisations visited a descendant of the original ‘Common Life’ house in Deventer. As there was an overlap in the 1950s and 60s between the Kabbalah groups and SES, we cannot be sure in which context the initial introduction of the Society of the Common Life arose. Although the name has had specific applications in different groups, the universality of its overall meaning has provided a very useful gateway, indicating that religion need not divide us, and that anyone from any faith or none will be welcome to study. By the same token, its a strongly-held principle that the name does not belong to any one person or movement; no one can lay claim to it. Perhaps, rather than pinning down the history of the name too specifically, it’s more fruitful to make use of its implications. The Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life opened the way to an individual spiritual path, which has served us right into the modern age. It is one which is not dominated by authority figures (or gurus), which recognises the commonality of humankind, and also the necessity of combining meditation with everyday life. Common Life Texts

Although some of the texts are hard to find, dense to read, and not always well translated, there is still much to appreciate. On a personal note, I began reading the writings of John of Ruysbroeck in the early 1970s, and have dipped into the history of the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life ever since, though not with scholarly application. But even if I have not worked as a scholar in this field, everything I present here comes from reliable sources. Exercises for ‘self-remembering’ and awareness With the left eye gaze at the transitory, and with the right the heavenly. Thomas a Kempis It was said of John Hatten, the cook’s servant at Deventer, that “Although with Martha he was attending in outward things, yet with Mary he was continually directing his attention towards those things which were needed and longed for ardently within, as much as he was able.” ‘The Brotherhood of the Common Life and its Influence’ - Ross Fuller (p112) The spiritual exercises and meditations of The Brotherhood of the Common Life were concerned above all with this movement between outer and inner life. The Devotionalist Rudolf Dier de Muden used to say: “My years are many and there is scarcely any fruit of them in me; pray therefore for me, that at least in my decrepit age I may be able to recollect myself.” ‘The Brotherhood of the Common Life and its Influence’ - Ross Fuller (p130) While I am seeking or doing anything outwardly, grant me grace to remember myself inwardly. William Peryn 1557 Quoted in ‘The Brotherhood of the Common Life and its Influence’ - Ross Fuller Now understand this: God comes to us without ceasing, both with means and without means, and demands of us both action and fruition, in such a way that the one never impedes, but always strengthens, the other. And therefore the most inward man lives his life in these two ways: namely, in work and rest… Thus the man is just; and he goes towards God with fervent love in eternal activity; and he goes in God with fruitive inclination in eternal rest. ‘The Adornment of the Spiritual Marriage’ Chap 65 - John of Ruysbroeck Instructions for meditation and contemplation Now if the spirit would see God with God in this divine light without means, there needs must be on the part of man three things. The first is that you must be perfectly ordered from without in all the virtues, and within must be unencumbered, and is empty of every outward work as if he did not work at all: for if his emptiness is troubled within by some work of virtue, he has an image; and as long as this endures within him, he cannot contemplate. Secondly, he must inwardly cleave to God, with adhering intention and love, even as a burning and glowing fire which can nevermore be quenched. As long as he feels himself to be in this state, he is able to contemplate. Thirdly, he must have lost himself in Waylessness and in a Darkness, in which all contemplative men want in fruition and wherein they never again can find themselves in a creaturely way. In the abyss of this darkness, in which the loving spirit has died to itself, there begin the manifestation of God and eternal life. ‘The Adornment of the Spiritual Marriage’ Chap 65 - John of Ruysbroeck ‘If… This good man would become an inward and ghostly (ie spiritual) man, he needs must have three further things. The first is a heart unencumbered with images; the second is spiritual freedom in his desires, the third is the feeling of inward union with God.… Further, you must know that if this ghostly man would now become a God-seeing man, he needs must have three other things. The first is the feeling that the foundation of his being is abysmal, and he should possess it in this manner; the second is that his inward exercise should be waylessness; the third is that his indwelling should be divine fruition.’ ‘The Sparkling Stone’ - John of Ruysbroeck The three rills This set of instructions for meditation written by Ruysbroeck hints at a practice which might have involved using the breath in certain ways to experience the ‘three rills’ of cosmic flow. At any rate, it suggests a profound form of contemplation, with distinct stages. Now Christ says inwardly within the spirit by means of this burning brook: GO YE OUT by practices in conformity with these gifts and with this coming. By the first rill, which is a simple light, the memory has been lifted above sensible images, and has been grounded and established in the unity of the spirit. By the second rill, which is an inflowing light, understanding and reason have been enlightened, to know the diverse ways of virtue and practice, and discern the mysteries of the Scriptures. By the third rill, which is an inpouring heat, the supreme will has been enkindled in tranquil love, and has been endowed with great riches. Thus has this man becomes spiritually enlightened; for the grace of God dwells like a fountainhead in the unity of his spirit; and its rills cause in the powers and out flowing with all the virtues. And the fountainhead of grace ever demands a flowing back into the same source from whence the flood proceeds. ‘The Adornment of the Spiritual Marriage’ Chap 38 - John of Ruysbroeck Books D’Aygalliers, A. Wautier - Ruysbroeck the Admirable (Original French edition 1923; English translation J. M. Dent 1925) Engen van, John (ed) – Devotio Moderna Paulist Press, New York 1988 Fuller, Ross - The Brotherhood of the Common Life and its Influence (State University of New York Press, 1995) Post, R. R. – The Modern Devotion (Studies in Medieval and Reformation Thought) Brill, Leiden 1968 Underhill, Evelyn – Ruysbroeck Selected works usually available by John of Ruysbroeck: The Adornment of the Spiritual Marriage The book of Truth The Sparkling Stone The Kingdom of the Lovers of God The Twelve Beguines Articles ‘The Quiet Revolution’, Robin Waterfield in Gnosis magazine, Fall 1992 ‘The Devotio Moderna’, Tony James (unpublished) Blog by Cherry Gilchrist The account above is a shorter and revised version of one which I wrote in 2018, for limited circulation among the current network of Saros and group. You are free to use the material, but please quote Soho Tree website (www.soho-tree.com) and Cherry Gilchrist as the source.

5 Comments

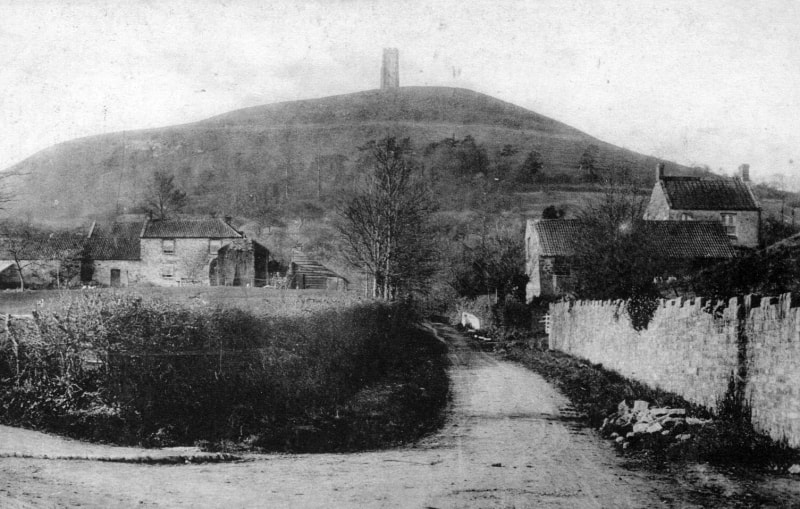

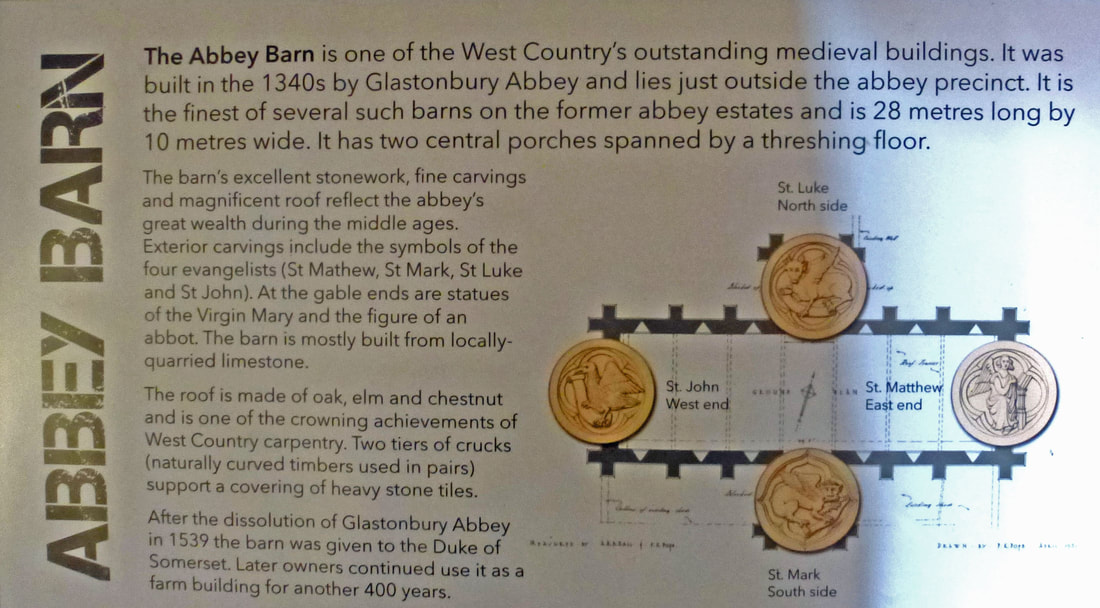

From the early days of ‘the Group’, its leaders and members regarded Glastonbury as a special destination. Individuals from subsequent London Cabbala groups in the 1960s and early ‘70s also headed westwards, to visit the town and surrounding area when the opportunity arose. Members from Tony Potter’s group, for instance, were encouraged to go, as somewhere to ‘recharge their batteries’. It was also a place to tune in to the unseen, to visit both Tor and Abbey, and ponder the intertwining of ‘native’ Christianity and more esoteric traditions. The visits of Alan Bain ‘Desolation and desecration. Sorrowful stones that lament past glories. They have no pride, no grandeur but a fierce sense of urgency that something must be done. They would be satisfied with nothing less than complete restoration in their original form, and this is impossible. Yet there is no despair, for they seem, also, to await the next chapter in the drama that is Glastonbury, almost as if they know what it is to be…’ So wrote Alan Bain, the main leader of the Soho Group, when he visited the town in 1960. ‘Its destiny’, he said, ‘is not yet fulfilled, if it ever will be...Holy it was, and Holy it is...That it exists at all makes me infinitely glad, but the state of its desolation leaves me correspondingly sad.’ It wasn’t his first visit to the town, and although we don’t have a full account of his journeys there, the notes that survive reveal that a couple of years earlier in 1958, he recorded a kind of pathworking, an imaginative visualisation of a pilgrimage to Glastonbury. In this, he ‘sees’ seven men walking to Glastonbury clad in white cloaks, then welcomed into the Abbey, where he notes in detail its layout and architecture at this apparently medieval period. This is how he describes breakfast on the morning after their arrival, when they have been lodged in the pilgrims’ quarters: ‘They then go along to building ‘W’ [diagram of Abbey supplied] which they enter, and sit down at a long bare wooden table and eat blackish bread which is very delicious, newly baked, with thick white (onion?) soup. A guide then enters, name of Jason or James, wearing a brown cloak with hood thrown back, not over head, a cord tied around his middle with tasselled ends. He has a plump figure and face and shiny bald head…He leads them to the Abbey.’ The pilgrims may be, he intimates, ‘the Company of Avalon’, a ‘Society’ which ‘had to do with magic’. In his later notes from 1960, he records an impression that his own ‘apprenticeship’ began in Glastonbury in 1523. Or was it, he asks, 1253? Either way, he plainly formed a strong personal bond with the Abbey and Glastonbury as an important centre of British Christian history, maybe even a form of esoteric Christianity. Alan took a series of photographs during his visit in 1960, and more later in the 1980s, some of which can be seen in this post. They carry the slightly melancholic atmosphere of Glastonbury in the middle of the 20th century, when it was less well-tended and less frequented than it is now. Alan's photos below show the passage from the Abbey to the High Street, the frontage of the ancient George & Pilgrim's Hotel, and the street itself. (The photos have been retrieved from his former website.) The British Jerusalem Glastonbury had long been a place of pilgrimage; it is sometimes called the British ‘Jerusalem’, as it is said to be where Joseph of Arimathea (the uncle of Christ) arrived in these Isles, bearing the sacred cup from the Last Supper. (At one time it was perfectly possible to arrive at Glastonbury by boat.) Joseph, so legend has it, planted his staff on Wearyall Hill where it sprang to life as a hawthorn bush. The Holy Thorn bush is still venerated through its descendants planted around the town to this day. It flowers both in winter and in May, and the Queen receives a spray of its flowers on her Christmas breakfast tray, a royal tradition stretching back to the reign of James I. Glastonbury has a layering of spirituality and myth which is unique in the British landscape. Its geography reinforces this mythical quality, with the high Tor towering dramatically over what was once an island in the Somerset Levels. It is startling even today when glimpsed on the approach to Glastonbury, and must have been revered by those arriving by boat, or over the causeways and ridgeways long ago. These flat lands were once waterlogged for much of the year, and in the Iron Age were inhabited by people who lived in lake villages. (See here and here.) The area is also connected with legends of King Arthur. His sword Excalibur is said to have been forged in Glastonbury, and a story tells how the Nine Sisters of Avalon bore the dying king across the lake to his final resting place in the immortal isles beyond. (See Chapter One, 'The Company of Nine', in my book The Circle of Nine ) Two springs – the White and the Red – rising at the base of the Tor, are also considered sacred and to have healing properties.  Alan Bain took these three images of the Red Spring and Chalice Well in 1960 - two of the well itself and one where the spring gushes out onto the lane, and people bring their bottles to fill up with the iron-rich water, said to promote healing and health In medieval times, Glastonbury was primarily a place of Christian pilgrimage, but after the Reformation, the Abbey fell into ruin. Then in the early 20th century, the town and the Tor began to draw in those interested in magical, psychic and visionary work – the Order of the Golden Dawn, Theosophists, psychical researchers, the Druid movement, and the Society of the Inner Light. The scene had already been set in the late 19th century, with the discovery of a purportedly ancient Blue Bowl. Rod Thorn’s account of this tells the tale: ‘The Victorian revival of Glastonbury as Avalon began here. A generation before Dion Fortune, a group of seekers played out a magical working in the landscape of Glastonbury, concealing and discovering a Holy Grail in the waters of an elusive well associated in legend with the goddess and saint Bride.’ (You can read the full story here.) The Spirit of Glastonbury In her book Glastonbury: Avalon of the Heart, the Inner Light’s founder, occultist Dion Fortune, tells us that there are three ways to arrive at Glastonbury: by road, through legend, or by less tangible means: ‘And there is a third way to Glastonbury, one of the secret Green Roads of the soul – the Mystic Way that leads through the Hidden Door into a land known only to the eye of vision. This is Avalon of the Heart to those who love her. The Mystic Avalon lives her hidden life, invisible save to those who have the key of the gates of vision.’ (p.1) Dion Fortune recognised, however, that there are different strands of interest running through the Glastonbury area, which sometimes come into conflict: ‘The Abbey is holy ground, consecrated by the dust of saints; but up here, at the foot of the Tor, the Old Gods have their part. So we have two Avalons, ‘the holiest erthe in Englande’, down among the water-meadows; and upon the green heights the fiery pagan forces that make the heart leap and burn. And some love one, and some the other.’ (p. 9) Alan Bain’s interest in Glastonbury remained firmly with its Christian heritage. He wrote on his website: ‘Glastonbury is regarded today by many as a place where, as Dion Fortune put it, "the veil is thin" [see below] …and it is this quality which imbues the site with its psychic reputation. In the eagerness for "New Age" developments and associated doctrines - mostly derived from theosophy - the essence of the legends, and possible psychic "facts" has become obscured by this same theosophical "New Age" overlay. But the mystery which is Glastonbury, and even its raison d'être is Christian, and bears little relation to so-called new age thinking…’ Dion Fortune was of course herself a Cabbalist, and as such was esteemed by Alan, especially as author of ‘The Mystical Qabalah’ which was the ‘set text’ for the early Group. Glastonbury was her part-time base, where she installed a large wooden cabin to serve as a guest house near Chalice Well, on the lower slopes of the Tor. (Benham p. 259). Although there are no known direct personal connections between the Group and Dion Fortune’s own ‘fraternity’, the Soho Cabbalists naturally paid close attention to Fortune’s written output, especially at a time where accessible and relatively modern works on Cabbala were scarce. And the milieu into which members of the Group stepped expectantly on arrival at Glastonbury, was largely created by the earlier interest of Dion Fortune and her followers, and by the mystical Christianity of Alice Buckton, who established a centre at Chalice Well. However, it was before the re-inflation of Glastonbury as a focus of New Age activity and the phenomenon of the Glastonbury Festival, which colour it today. In fact, Glastonbury has a long, fluid history, so portraying its ambience at a particular period of time can be tricky. I first visited Glastonbury around 1966, as a teenager; I begged my parents to let us stop off on the way home from a holiday in Torquay, as I had been influenced by notes I’d read about the town and its mystical history for my A Level text of Tennyson’s Morte d’Arthur. So I can at least recall from personal experience the difference between then and now, between the Glastonbury visited by group members from the late ‘50s to the early ‘70s, and the busy hive of mystical activity that it is today, not to mention the increased commercialism in shops selling crystals and wizards' cloaks! Back in the mid-20th century, it was a less visited, more overgrown, and somewhat more brooding place than in its present incarnation. ‘When history is in the making, as it is at Glastonbury, it is impossible to assess it at its real value. One can think of it only as it affects oneself…Glastonbury has ever been the home of men and women who have seen visions. The veil is thin here, and the Unseen comes very near to earth…’ (Fortune p.59). The Journey to Glastonbury Another factor to take into account is that it was far less straightforward to get there by road in the ‘50s and ‘60s. From London to Glastonbury is around 140 miles; the M5 and M4 motorways which we might use today, weren’t completed until the 1970s, so even travelling by ‘A’ roads could be very time-consuming. In holiday periods, hours extra were added on as traffic attempted to get to and from West Country seaside resorts. Dion Fortune describes the journey evocatively, romantically even, describing a gentle motor trip pootering through the different soils and terrains of England, over the heathlands of Hampshire and past the awe-inspiring Stonehenge, until finally entering the apple orchards of Avalon. But the reality for the post-war travellers of the Group – who often hitch-hiked anyway - was countryside buried under urban expansion, hold-ups with road works, and heavy traffic. It was a triumph for them finally to arrive at Glastonbury, but in a rather different sense to earlier seekers. They could not be sure of a warm welcome either. From the late ‘60s onwards, notices declaring ‘No Hippies’ began to appear in guest houses and restaurants. As a student at the time, my boyfriend and I struggled to find accommodation, and were finally directed by some guffawing locals to ‘Go down The Lamb! The Lamb’s the place for you.’ And indeed the rough-and-ready Lamb Inn took us in without demanding a marriage certificate or a haircut. Chalice Well too was guarded by elderly and suspicious ladies who did not welcome the youthful invaders of their sanctuary. The Visits As the Group began to branch into different Cabbala teaching groups, each leader took their own view of Glastonbury and passed it on in one form or another to their members. Stan Green recalls that in Tony Potters group: ‘Annually, at the Spring equinox we went to Glastonbury, acknowledged as a centre of esoteric power, to "recharge our batteries" as Tony put it.’ John Pearce, artist and fellow group member, was drawn back to Glastonbury on a number of occasions. The accounts he wrote of several visits, which he has shared for this article, show how Glastonbury could be a crucible for inspiring magical activities. It was a place where anything, it seemed, might happen, or could be encouraged to happen: (Returning from Cornwall in 1965) 'I continued eastwards to Glastonbury, by bus, train, hiking or hitch hiking. A Glastonbury shop window displayed a wicked-looking commando knife which I immediately bought, seeing it both as an ‘Excalibur’ and as a possible ceremonial accessory. Nowadays one should be arrested for carrying such an item, but at the time Boy Scouts still wore large sheath-knives, and I had no such fears. ‘In 1965 the great Abbey Barn, now a Rural Life Museum, was still in agricultural use. I asked no-one’s leave, and camped in the field next to it (now an extensive housing development). Admiring the barn itself, I saw it was cruciform, its four gables sporting the symbols of the four evangelists, approximately aligned to the cardinal points of the compass: the ox on the north gable, lion to the south, man to the east and eagle to the west, representing also the four elements and the four fixed signs of the Zodiac: ox, earth (Taurus), lion, fire (Leo), man, air (Aquarius) and eagle, water (Scorpio). On that basis I performed the Lesser Ritual of the Pentagram inside the barn, employing my newly bought ‘dagger’. Invoking or banishing? I can’t remember, but the overall consequence seemed efficacious and continued after my return to London.’ John Pearce’s interest had been kindled, and was further aroused when other synchronicitous events occurred: ‘In the early 1970s I made several more visits to Glastonbury...One which I made in 1970 was with Peter Westerman, who at the time had the use of a Ford Box van, his work being antique removals. We cooked and slept in the van, parked on Wellhouse Lane on the lower slope of the Tor. On the morning of our departure we found the vehicle wouldn’t start; there was no electric current. Fortunately the van was pointing down the gentle slope towards the town, so one steered and the other pushed, and many attempts at bump-starting were made en-route. Despite the helpful gradient it had been hard work. When we reached the edge of Glastonbury we parked and prepared to summon help. Before we could do so a diminutive bald gentleman came eagerly down his garden path from the nearest house and invited us in for morning coffee! This in itself seemed remarkable, and we had a pleasant morning of coffee, biscuits and chat, but more remarkable was that on returning to the van it started at the first attempt and gave no further trouble.’ The memoir of John’s visit at the Autumn Equinox, 1970, can be accessed below, with its account of encounters at the Tor and unusual lights flickering on its tower. It also reveals another aspect of the area, namely the dynamic tension between Glastonbury and the nearby city of Wells, with its famous Cathedral. Each has their own powerful atmosphere, and individuals may find it hard to withdraw from the pull of one to enter the other. The account also highlights the tussle within the hearts of some group members as to whether to fully accept the Christian path or not.

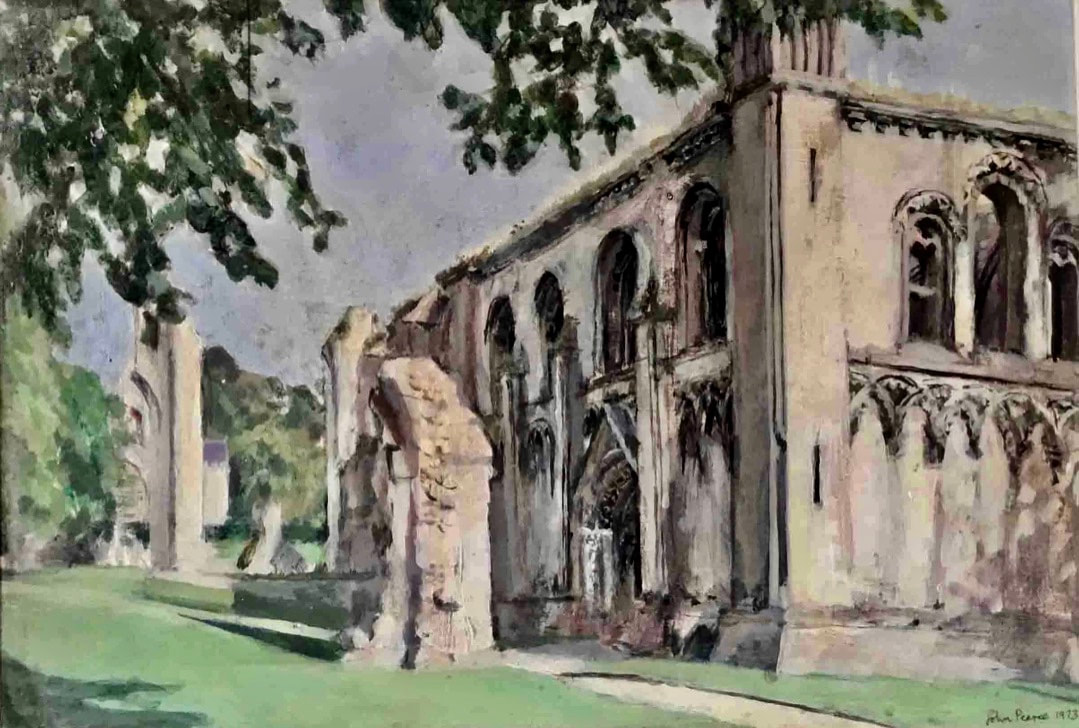

John Pearce’s account of the Spring Equinox in 1973 includes another tantalising description of strange lights on the Tor, this time seen through his guesthouse bedroom window: ‘I slept well, but woke suddenly in the small hours and saw St Michael’s tower silhouetted against a pre-dawn sky, with mercurial silver lights shooting vertically up at its edges like champagne bubbles. I went back to sleep - but I know I didn’t dream it. I assumed there was a scientific explanation. Next day I looked for evidence of fireworks, or any reflective features that could have caught headlights, but could find nothing to account for what I’d seen.’ During this visit, John also painted various Glastonbury scenes, and his picture of the Lady Chapel at the Abbey is shown below. Glastonbury wasn’t for everybody, and his fellow group member Stan Green became wary of its so-called enchantment, even though he acknowledged its visionary dimension, which he encountered on his first visit in about 1962: ‘I do remember a woman who was some kind of caretaker, showing us round. At the Well she said that she had seen in meditation, a passage going from the Well into the centre of the Tor.’ But the effect palled: ‘Our visits to Glastonbury were more like school outings with giggly children running up and down the Tor and in and out of the Abbey, than mature contemplatives. My fascination wore off after maybe the second or third visit.’ Glastonbury was tangential to the main work of the first Group and those which followed, but it certainly helped to illuminate some of that work. The kind of pathworking exercises and visualisations sometimes conducted in the groups gave a good training in using intuition and active imagination, and also encouraged sharp observation, and a neutrality which meant accepting visions and imagery as ‘interesting’, but not as concrete evidence. (Very useful in the imaginative climate of the town!) They had also learned something about ritual practice, which enabled them to respond to the situations which arose, and emotional charge of ‘the Glastonbury experience’. And the kind of synchronicities that tend to arise on visits to Glastonbury, were both a validation and an encouragement of the philosophies they had been practising. Glastonbury remained of great significance to Alan Bain, as he and his wife Margaret decided to move down to the area in 1963. Group member Norman Martin recalled how he and his wife also decided to leave their Clerkenwell home for Glastonbury. His wife went round Alan’s place in London to tell him, but only Margaret was there, who said, “Oh – Alan’s just gone down to Glastonbury, can you take his piano accordion and motorbike down with you?” Norman somehow managed to load them into his car, but the car broke down at Reading. In the end, however, he did get them to Glastonbury. As two other accounts in this blog also illustrate, journeys to and from Glastonbury could involve mysterious difficulties with transport! Perhaps visiting Glastonbury was more congenial than living in it. Within a few years, Norman moved up to Bristol to carry on his jewellery work, and Alan moved to Bath. Glyn Davies, the third key leader of the Group, and initiator of Saros, had a very particular relationship with Somerset and Glastonbury. Although he was born into a Welsh family in Llanelli, he spent nearly ten years of his childhood living with relatives in Somerset in the Highbridge area. This was due partly to family complications, and the fact that he had relatives fitted with the strong historic pattern of migration between South Wales and Somerset, because of the shipping via the Bristol Channel. As Glyn wrote in a letter in 1968, when asked to give his former addresses: ‘I can start from the age of nine or ten years. No. 1 Carters Cottage, Stretcholt, Pawlett, Somerset. No. 2 11 to 18 years, 58 Church Street, Highbridge, Somerset.’ (Images below are from a recent sale of Carter's Cottage, Stretcholt) By the time I met him in 1970, he had frequented Glastonbury for many years. This was only about twenty miles from the Somerset haunts of his youth, and quite probably he had visited it before he even came into contact with Cabbala while serving in the RAF from 1947-57. He continued to feel a link with Somerset as a whole, and rented a little cottage in the Mendips to write his novel ‘Circum’ around 1966. The novel is partly set in that Somerset countryside, and the coastal resort of Burnham-on-Sea which Glyn knew so well. And in 1967 he took Gila, his wife-to-be, to show her the Abbey, and to climb the Tor. As he was to some degree a native of the area, his view was almost certainly different to those coming to Glastonbury as expectant pilgrims, and he probably had a more realistic take on the Glastonbury mix. The Somerset Levels also have elements of poverty, a dislike of incomers, and their own uproarious customs like the annual Carnivals, which take place as the darker months of autumn descend and are celebrated in the traditional way, with plenty of drink and flashing lights! Glyn cherished the mysticism of Glastonbury, but understood its place in the Somerset landscape. He told me that he had once slept for three nights in a row on the Tor: ‘And then I understood what Glastonbury is all about’. ‘So what is that?’ I asked him, but he would never tell me! He did however also say on another occasion that it was ‘cloud cuckoo land’, not necessarily in terms of fantasy, but as a place of dreams and a melange of mystical aspirations. ‘You can feel that cloud descending when you’re still a few miles out of the town.’ He was very familiar with the site of Dion Fortune’s house there; on a visit in 1971, he took my husband and I to see it immediately we arrived in the town, because he loved the view from there so much. We had driven down in our little ex-post office van and the three of us embarked on a ‘magical mystery tour’ of the West Country, of which Glastonbury was the first port of call. On the way back, we detoured via Cheltenham to meet magician and writer Bill Gray, another acquaintance of his. Glyn also solved a problem with our van that even the garage hadn’t been able to fix. It was in the habit of slowly juddering to a stop, and wouldn’t start again for twenty minutes or so. When this happened on our trip home, Glyn walked around the car thoughtfully, then asked, ‘Do you have a pin?’ I found a safety pin, he did something around the back, and the van started up again beautifully and never misbehaved again. ‘Airlock,’ he said. ‘Just gave it a couple of pricks.’ We’d bought a new rubber petrol cap a few weeks before, and it was forming a vacuum in the pipe. He had, after all, been classed as a ‘fault finder’ in the RAF radar department! Did Glyn have any special contacts in the Glastonbury area? His own teacher came from Yorkshire, but during the years that he began to practice Cabbala, he made it his business to make many contacts in esoteric circles, and to understand how they worked. One possible source or contact has come up through our more recent research, which is Ronald Heaver who presided over the Sanctuary of Avalon. He was a significant figure in the area at the time, whose approach was to some extent aligned with ours; he also had a wide network of contacts. It seems very possible that Glyn could have known him, and an account of Heaver and his Sanctuary can be found below.

Winter Solstice at Glastonbury, 2003. (Photo Cherry Gilchrist) Winter Solstice at Glastonbury, 2003. (Photo Cherry Gilchrist) Conclusion This is just a glimpse of how members of the groups related to Glastonbury, and is certainly only just a snapshot of the history and significance of the place. My brief here has been to describe what we know of members’ experiences, from material to hand, and to show something of the connection between the town and the work of the groups. No one from these groups, as far as we are aware, remained permanently in Glastonbury or even lived there a long time; in some ways the Glastonbury ethos was counter to the more clear-sighted attitude of the groups, where synchronicities and visions are considered meaningful, but are not ultimately the goal of ‘the Work’. Cherry Gilchrist References Glastonbury: Avalon of the Heart – Dion Fortune. First published in 1934, this is an evocative reflection upon the town and its significance, as she knew and experienced it. The Avalonians - Patrick Benham – an excellent historical account of esoteric activity and lines of work in the area A Glastonbury Romance - John Cowper Powys. A long, complex but beguiling novel which captures much of the spirit of Glastonbury, and the different strands running through it. Set in in the 1930s. Circum – W. G. Davies (published privately) – a novel with an esoteric underly; each of the 22 chapters is based upon a Tarot card. Set partly in Somerset. Acknowledgements With sincere thanks to John Pearce for sharing his memoirs and art, Stan Green for his recollections, Gila Davies (Zur) for permission to post the photograph of her visit to Glastonbury. Also to R. J. Stewart for inviting me to visit to his current-day Sanctuary of Avalon on the side of the Tor, and much interesting discussion and correspondence about Ronald Heaver and other stalwarts of Glastonbury. Warren Kenton died on Monday night of cardiac arrest at age 87. Warren, also known as Z'ev ben Shimon Halevi, was a teacher of Kabbalah with a world-wide following. He wrote many books about Kabbalah during his life, starting with The Tree of Life in 1972. Warren learnt Kabbalah originally through a group led by Glyn Davies, when they were both in the School of Economic Science (SES). Warren recalls in his autobiography that Glyn once told him that his own teacher had said to him ‘We need a writer to present the Tradition for the current generation’. Warren took on this task, to clarify Kabbalah and update its mythology and metaphysics in terms of modern science and psychology. As he developed he forged his own connection to the tradition. As he said in an interview in Gnosis Magazine in 1996: “As regards my teachers, there are two kinds. There’s the physical one who introduces you to the basics, and then there is the interior teacher. This is something that one can’t say a great deal about, because you have to experience that kind of interior conversation, with what is called in Kabbalah the Maggid, one’s teacher.” Warren travelled widely, running courses around the world. He was a fellow of the Temenos Academy and a founder member of the Kabbalah Society, teaching the Toledano line of Kabbalah. Joyce Collin-Smith, in her book Call No Man Master, shares a nice memory of Warren. She had spent much time with various famous spiritual leaders in the 1960s, but had come to feel much happier studying Kabbalah in Warren’s group in London. She writes: “Occasionally Warren invited me to stay on and have a late supper with him, if I was spending the night with friends in London. When the others had gone, he would become, not the doorkeeper for a master, (as he liked to describe himself), but an ordinary friend and confidante, with a great sense of humour and an enormous fund of exceedingly Jewish jokes. Between laughter we would eat and talk as equals on all manner of subjects, gleaning from each other. But in his meetings I have always deferred to him with great respect.” Fare Well Warren! Further information: First Kabbalah Book: An Introduction to the Cabala: Tree of Life (Rider, 1972; Samuel Weiser, 1991) Autobiography: The Path of a Kabbalist (Kabbalah Society, 2009) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Z'ev_ben_Shimon_Halevi https://www.kabbalahsociety.org/ https://toledanotradition.com/ Blog by Rod Thorn Soho, tucked into the very heart of London, has been a melting pot of people and culture for a hundred years or more. The arrival of the espresso bars there in the 1950s opened up a whole new phase of possibilities for meeting up, hanging out, and sizing up potential allies. ‘The Group’, as the original Cabbala group of this website was known, first came together in these coffee bars in the late 1950s. Here three key figures held court - Alan Bain, Glyn Davies and Tony Potter – offering debates and discussions to anyone interested in new horizons and ‘the big questions’ of life. Although some of this background has been covered in earlier blogs here (links to the first of a sequence of related posts), it’s worth a further look at the unique Soho café culture of the period, which provided a unique milieu to find kindred spirits. ‘The fifties were a time of austerity, of punitive conventions, of a grey uniformity….Soho was the only area in London where the rules didn’t apply,’ said critic and musician George Melly. A note on geography: In keeping with various other studies and memoirs of Soho coffee bars, I’m stretching the geographical boundaries a little wider to include neighbouring areas. The café habituees of the time didn’t draw a hard line where Soho officially ended: people spilled across the Strand towards Charing Cross and up towards Covent Garden market when staking out their favourite haunts. This applies to Group members too. The Soho Crowd For some, entering the Soho scene was primarily a chance to break free of stuffy rules and live on the wild side. For others it offered a source of artistic inspiration and experiment. But for others still, it was a place where you could be a seeker of knowledge, in a more spiritual sense. However, it wasn’t about narrowing down your network, in your quest to find kindred spirits. Once you had found your particular tribe, you could make that a focus while still mixing freely with a fascinating variety of people. The common ground was often music: live rock and roll, skiffle, folk and blues were a key feature of many coffee bars. Several members of the Group were proficient musicians, and music may have been the reason why they were on the Soho scene in the first place. Soho was not just coffee bars of course - many artists, for instance, preferred drinking in its pubs –nor was the coffee bar unique to Soho. Once the new concept had taken off, around 1952, espresso bars with Gaggia machines sprang up like hissing mushrooms all over London. There were some 600 in business in the capital by 1960. But the combination of the cafes and the Soho scene provided something special, which early Group members took advantage of. This scene emerged at a point of change in society, about a decade after World War Two ended. Post-war Britain may have been a dreary society in many respects, but here in the centre of London, possibilities were sizzling. It was the kind of moment which arises every now and then, when new impulses arise and can take root. In the case of the Group, what came out of those gatherings is still going strong, in different forms, some sixty-five years later. Perhaps this wasn’t just chance, and perhaps we are on the brink of another kind of change? As my colleague Richard Smoley points out: ‘Gurdjieff said that during times of upheaval, unusual amounts of knowledge are set loose and made available. He was thinking of the Russian Revolution, but we could ask whether the huge amount of knowledge that was made available in the last quarter of the twentieth century was to prepare us for these upheavals.’ (Recent email correspondence.) The Coffee Bar Scene To open a door into the world of Soho coffee bars, here is an extract from an internet memoir by ‘Goosey Anne’, (real name unknown, and not a member of the Soho Group): I was living and working in London in the early 1950s and most of my leisure time was spent in the newly-opened coffee houses in and around Soho. These were the haunt of the bohemians – artists, writers, `resting` actors, musicians and `characters` closely followed by students, nurses and people like me who had a good day job but enjoyed their company in the evenings. It was a mainly harmless pursuit – we would meet at one given coffee bar and during the course of the evening make our way onto a couple of others. The new Gaggia coffee machines were installed in most of the places – huge, glistening chrome affairs that hissed steam into the air to mingle with the cigarette smoke, for nearly everyone smoked and the atmosphere was pretty fetid. Coffee cost 9d (old pence) and usually we would all make one cup each last all evening. We would sit and talk and talk and talk – putting the world to rights. No drugs ever came my way and indeed had that happened I would have refused. I only knew two of the circle who took drugs – we actually felt sorry for them. Most evenings someone would bring a guitar along and another person bongo drums and a sing-song of mainly Folk Songs would begin. One particular coffee bar – The Gyre & Gimble had a resident guitarist – Dorian – who would play softly in the background and compose witty ditties about the customers which he would almost speak in his educated drawl as he played. In one place – Bunjies – one of our group composed a song which went something like this: ‘"Sitting in Bunjies my heart began to throb – for one cappuccino would set me back a bob. And for a sandwich I`d have to sell my soul; for six weeks I`ve saved up to buy a sausage-roll". The owner didn`t like that tune much and would threaten to throw us out. But it was mainly Folk Music with the odd Rugby song thrown in if the University students were about.' Why Coffee Bars? One of the great advantages which coffee bars had over pubs, is that they could stay open later, as they weren’t subject to licensing laws. And anyone could go into a café, whereas there was a minimum age of 18 for drinking in pubs, which could also be intimidating places for women at the time. Cafes suited the new culture of juke boxes, and also live music; they commonly included a space for dancing, or for musicians to play in the evening. The ‘50s coffee bars were not just a teenage haunt either, as they appealed to a very wide cross-section of clientele, including shoppers and beatniks, philosophers and prostitutes, office workers and film crew. This could vary through the day, with the afternoon crowd being a different mix of people to the evening regulars. To youngsters leaving home, or ex-National Service recruits now making their own way in life (as several Group recruits were), this must have enhanced the sense of Soho as a great adventure. After the privations of war, there was a new spirit of freedom; more of the class barriers were breaking down, and Soho was the obvious destination for creatives, seekers, eccentrics and simply those who were tired of the old conventions. No doubt the vices of Soho were feared by parents of teenage children, and by those who never dared set foot in such a disreputable area. But, as Goosey-Anne says, drugs were not often on the agenda, and those who preferred strong drink chose the pubs instead. In fact, according to the film ‘Beat Girl’, the message among the teens themselves was that ‘drinking is for squares!’ (Beat Girl starred Adam Faith, the soon-to-be pop star, and its cinematographer was Walter Lassally, a central member of The Group. See the blog about him here.) The clip below features the theme tune by John Barry and the opening sequence, with a very young Oliver Reed jiving in a plaid shirt. Opening a Coffee Bar Property was cheap to rent in Soho in the post-war period, so opening a coffee bar was a great little start-up business. In 1956, the humorous magazine Punch declared: ‘We have reached the stage where virtually the entire population of these islands goes in hourly danger of opening a coffee-bar.’ Tony Hancock, one of Britain’s best-loved comedians, took this further. In one of his sketches, he and his mate are casting around for a scheme which will make them a bit of money: Hancocks Halfhour – The Espresso Bar (1956) Tony: When actors are not working, where do they hang around?...We are going to provide them with such a place! We are going to open an Espresso Coffee Bar!’ Mate: ‘Oh no! We’re not the type’ Tony: ‘No, but we can soon remedy that. Buy a couple of duffle coats, a pair of corduroys, rope sandals, grow our hair long – we’ll be a sensation!’ Mate: ‘You don’t only get the layabouts in, you know. You get the youngsters, and the intellectual bohemians.’ Tony: ‘Intellectual bohemians – I’ve watched ‘em. They’re all broke. They don’t buy anything.’ Mate: ‘No, but the people who come in to look at them do!’ So the coffee bar crowd not only drew the beatniks, and the intellectuals, but also generated its own kind of tourist trade. Hancock goes on to envisage how the Guards officers would bring their debutante girlfriends to gawp and giggle, on a racy night out on the town! Image Creating the right image for your coffee bar was of prime importance. A funky name went down well – perhaps something Italian or Spanish like Il Toro, or arty like The Picasso, or musical like Freight Train, or melodramatic like Heaven and Hell. (All these were popular Soho cafes.) Décor was important, but could be done cheaply. Popular finishes were murals (plenty of young hopeful artists to paint them for next to nothing), brick-patterned wallpaper– or just the real thing, bare bricks. Bamboo furniture and plastic tables were inexpensive, and imaginative recycled lighting helped to create atmosphere. Some cafes went further. As one blog comment put it: ‘At Le Macabre you could have your coffee on a coffin in a cobweb festooned house of horrors, wearing sunglasses at night whilst having earnest discussions about the difference between Jean Paul Sartre and Dizzy Gillespie.’ Affirming your identity Choosing your coffee bars went along with choosing your circle and affirming your identity. Keith Barnes, a core member of the early Group, recalls that there were different circles in Soho. He was, as he put it, at the bottom in the beat circle, wearing his duffle coat and a sweater, and sporting a dirty beard. The musicians, he said, were a rung higher up the ladder as they were paid for what they did. When Keith joined the Group, its favourite cafes (which I’ll list later) became his main hangouts. But even if you stayed mainly with your own group, the chances were that you would mix with a very wide range of people. Keith met a few of the prostitutes, and observed how they liked to stand above one of the hot air vents on the pavements, to warm their legs! Once, when he had no money, two prostitutes bought him a meal to help him out. He never saw them again, and says that none of them ever showed an interest in the Group. The name you were known by Nicknames were de rigeur, especially for musicians. Keith was known primarily as ‘Peanuts’, and it took us a long time to trace Fritz Felstone’s identity in our Saros Roots research, until we discovered that he was really called Brian. Alan Bain’s brother, Bob Bain, adds: ‘I recall Mum (desiring to speak with her "Bohemian" son) taking me to where he might be found which was probably Gyre and Gimble but when asking for Alan Bain there was seemingly a look of 'Who?" followed by "Oh, you mean Max!"’ Did this habit have its roots in the jazz culture? A Wikipedia article takes it very seriously: ‘Nicknames are common among jazz musicians…Some of the most notable nicknames and stage names are listed here.’ There follows a list of well over one hundred names, including 16 musicians who chose to call themselves ‘Red’. The Musicians of Soho Keith himself played and busked in the musicians’ cafes, and a number of Group members did likewise - Alan Bain with his piano accordion, and Fritz Felstone with his banjo, for instance. Quite probably some of them first met each other in these haunts. One of the prime musicians’ cafes was the Nucleus, known as ‘the Nuke’. ‘The 2 Gs’, in John Adam Street was another, and a favourite of the Group. Its full name was the Gyre and Gimble, but according to Keith, ‘only the tourists called it that’. Goosey Anne recounts: 'Of course this music played in the coffee houses was the beginning of the Skiffle and later Rock `n Roll era which I just missed. Apparently Tommy Steele used to come into the Gyre & Gimble and play his guitar rather tunelessly and people would ask him to stop! ' She is not the only one to refer to Tommy Steele’s first and rather awful efforts there! There is an account of somebody hitting him to try and shut him up. But, like Tommy Steele (born Thomas Hicks!) a number of musicians began their rise to fame from these early sessions in the clubs and cafes of the Soho area. And Keith goes on to say: ‘Sometimes the musicians would hang out in the 2Gs, then walk over the river to busk at the National Theatre. Musicians like Red Sullivan, Martin Windsor, Wiz Jones. Fritz from the Group played the banjo with them.’ Group Cafes The gatherings of the Group took place chiefly in the ‘2 Gs’ in John Adam Street, the Cross, and the Florence in nearby Villiers St, with Lyons Corner House on the Strand playing a part too. All the regular haunts were therefore near Charing Cross. It was possible to eat cheaply in some of them as well - getting a filling bowl of stew or pasta was essential. Not many in the Group were earning much, if anything, so these venues could feed the body as well as offering succour for the soul. This also fitted in very nicely with Alan Bain’s personal arrangements. Norman Martin, jeweller and Group member, recounted how at one period, both he and Alan had ‘offices’ upstairs in the same building as the 2 Gs, which had its home in the basement. He admitted that they also surreptitiously used these offices to live in! By day, the bed was rolled away so that there were no traces of their overnight stay. But, Norman said, the landlord did twig what was going on and eventually they were thrown out. Alan Bain also had a bookshop in that building, next to the doorway into the Gyre and Gimble, which can be seen in two old photos in posts here and here ('Historical Sketches in Esoteric Britain') . A couple of years ago, when Rod Thorn and I visited the Mexican basement café which once housed the 2 Gs, the waiter we encountered was astonished to learn that it had once been a famous café, and that Tommy Steele had played there! The cafes were fine for open chat, where newcomers could join in discussions, and regulars could track down their fellow members. But for those who sustained a spark of interest, invitations would be given discreetly to the ‘real’ meetings, which were held behind closed doors. Here Tree of Life Cabbala was studied, as described in a previous post. However, there was never any pressure to join, and it was up to the individual whether he or she stayed or left the Group. Even when the transition to closed group meetings had taken place, full Group members still frequented the cafes as and when they could. As Lionel Bowen writes: ‘I spent a lot of time in the ‘Gyre and Gimble’ coffee house on John Adam Street close to Trafalgar Square. We drank espresso, played bad guitar and sang (poorly) folk songs. The elder members of the Group hung out there I think, on the lookout for likely recruits.’ Micks All-Nighter Another favourite café was ‘Micks’ (no apostrophe - see below) on Fleet Street. Although this wasn’t so much of a meeting place for the group, it was a welcome resource for all-night cheap eats, and was often frequented by Keith Barnes and Glyn Davies after they’d put in long hours on jobs, such as washing up in hotels, in order to pay the rent. ‘You would often see quite famous musicians bombing along there in Ford vans driving at 70mph delivering newspapers – they took on these jobs because they couldn’t earn enough from their music.’ A former police officer, interviewed for ‘Spitalfields Life’, remembers it well from slightly later, in 1972: 'Micks Cafe in Fleet St never had an apostrophe on the sign or acute accent on the ‘e.’ It was a cramped greasy spoon that opened twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. During the night and early morning it served print-workers, drunks returning from the West End and the occasional vagrant. Generally, we police did not use it. We might have been unwelcome because we would have stood out like a sore thumb. But I did observation in there in plain clothes sometimes. Micks Cafe was a place where virtually anything could be sourced, especially at night when nowhere else was open.' Recollections of the café also pop up in Fleet Street memoirs: 'Working through the night was thirsty work and John recalled how the ink-stained printers would rub shoulders with the ‘toffs’ on their way back from London nightlife, in a “Mick’s Café”, as part of the Fleet Street tradition.' Messenger Boys had a special relationship with it: 'First job at 8.00am was to go to Westminster Press and collect the days national papers, these were then checked for previous days publications, then came the most important job of the day, this was taking a large silver teapot down to Micks Cafe in Fleet Street and getting it filled with tea and also ordering toast for the Darkroom and Bench staff.' A Day In The Life Of A Fleet Street Photo Press Agency -1960’s Micks thus had the same mix of working people, musicians, eccentrics and high society, which characterised the nearby Soho cafes. However, it has a special claim to fame as the all-night café featured in the well-known song ‘The Streets of London’, by Ralph McTell. (This YouTube version has a fine set of photos and street scenes accompanying the song.) The Mix We only have detailed information about this one specific group following an esoteric pursuit in the Soho coffee bars. However, there were certainly other circles with their own esoteric interests; I’ve come across mentions of a Mithraic order, and Druids, and there was widespread interest in astrology. ‘Sun sign’ newspaper columns had become prevalent since the 1930s, and people were keen to know more about their horoscopes. Ernest Page, the eccentric and very accomplished astrologer, was usually to be found somewhere in Soho, and instructed members of the Group in astrology, as we’ve seen in another blog (Ernest Page) . He is also recalled by many other Soho seekers of the era, as in this discussion forum: 'I well remember Ernest, the elderly astrologer (well, I was early 20s) giving me a reading for the price of a coffee or two!' 'The astrologer was named Ernie Page an ex postman. Long grey hair, hunched shoulders and carrying a small suitcase with his astrology charts. He used to prefer Sam Widges’ Coffee bar to the 2Gs. He often kept company with a ladyboy prostitute called Angel.' In the photo below, extracted from a short video on Soho Coffee Bars, Ernest discusses astrology with Glyn Davies and Tony Potter from 'The Group'. Alan Bain acknowledges what an excellent teacher he was. Sources and Perspectives One of the fascinating aspects of studying the Soho area scene in the 1950s and early ‘60s is that it’s possible to home in on a particular coffee bar, and learn about its music, clientele, and stories, through detailed eyewitness accounts. But those who are left to bear witness are diminishing in number, so it’s important to catch their stories while they’re able to tell them. We're very grateful that we’ve had the chance to talk to several Group members about their experiences, and also glad to find more general personal memoirs of Soho cafes on internet discussion forums from the last fifteen years. But it’s also possible to pan out to see the whole vista, as an exciting mix of influences, and a scene which at that time was a free flow of creativity and quests, and where an extraordinary collection of people met and mingled. In this respect, there’s been a growing interest in this era of Soho over the last few years, and a number of published books and papers have taken its history seriously. These too have helped to shed light on a milieu that is truly intriguing, and which served as a kind of cradle for the Group in its infancy. References